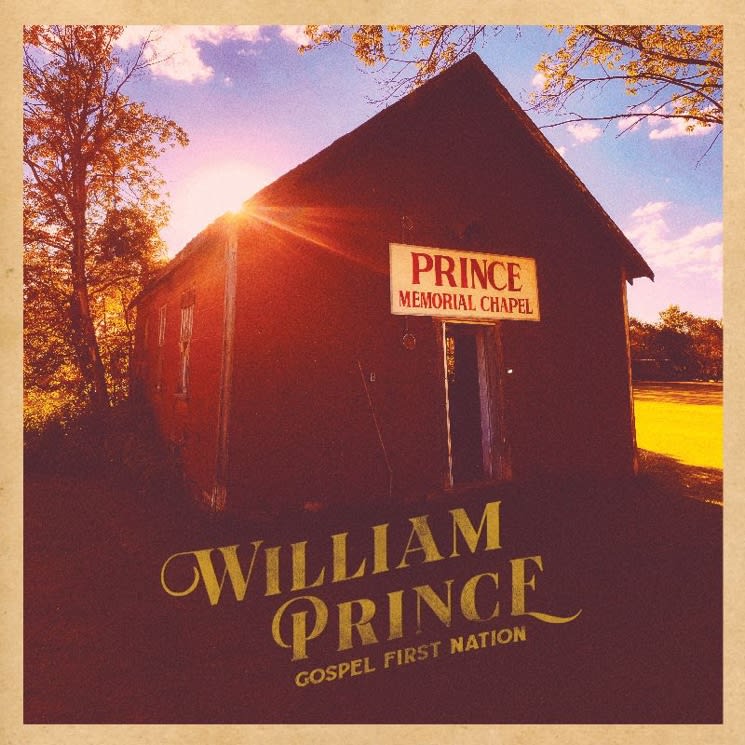

William Prince's Gospel First Nation is an incredibly complicated record that sounds like a summer breeze. Raised in Peguis First Nation, Prince comes from a long line of preachers and his latest is a careful and subtle navigation of his Christian upbringing and the significant role that the church has played in attempting to eliminate Indigenous identity.

It's a tricky and, to many, a likely impossible gulf to bridge. But Prince seems acutely aware that his formative associations with church and prayer are perhaps an outlier among Indigenous people, and the crux of Gospel First Nation is that friction.

But to hear Prince sing it, it doesn't sound much like friction at all. For all the painful histories and social intricacies at the heart of this record, it feels as though Prince has found some sort of solace at his spot between worlds. Gospel First Nation is his attempt to give this in-between place a song. Prince is one of Canada's finest living songwriters — capable of softening even the hardest truth into a warm reassurance.

However, Gospel First Nation finds him mostly singing the words of others, with only three tracks penned by Prince himself, one being the waltzing "When Jesus Needs an Angel," which was written when Prince was only 14. Those familiar with Prince's first record of 2020, the beautiful Reliever, won't be surprised by any of the music on Gospel First Nation. These are gospel songs in spirit more than execution, with Prince leaning into his classic country sound more completely than before. He bathes his unfussy arrangements in gentle strings, brushed percussion and glittering threads of pedal steel; when a choir does appear, it's soft and supportive, a whisper from the reeds rather than a shout from the mountaintop.

Unsurprisingly, the best song here is one of Prince's own. The title track, with its complicated sense of faith and beautiful lyrics — "You could sit for hours and / only hear the sound of / the trees keeping the lake and sky apart" — is the record's unquestionable peak. Gospel First Nation is a lovely record, one that raises difficult questions without ever asking them directly. It's a document of one man's relationship to family and faith, of reclamation and history and the unknown, suggesting that perhaps everything is connected after all.

It's a tricky and, to many, a likely impossible gulf to bridge. But Prince seems acutely aware that his formative associations with church and prayer are perhaps an outlier among Indigenous people, and the crux of Gospel First Nation is that friction.

But to hear Prince sing it, it doesn't sound much like friction at all. For all the painful histories and social intricacies at the heart of this record, it feels as though Prince has found some sort of solace at his spot between worlds. Gospel First Nation is his attempt to give this in-between place a song. Prince is one of Canada's finest living songwriters — capable of softening even the hardest truth into a warm reassurance.

However, Gospel First Nation finds him mostly singing the words of others, with only three tracks penned by Prince himself, one being the waltzing "When Jesus Needs an Angel," which was written when Prince was only 14. Those familiar with Prince's first record of 2020, the beautiful Reliever, won't be surprised by any of the music on Gospel First Nation. These are gospel songs in spirit more than execution, with Prince leaning into his classic country sound more completely than before. He bathes his unfussy arrangements in gentle strings, brushed percussion and glittering threads of pedal steel; when a choir does appear, it's soft and supportive, a whisper from the reeds rather than a shout from the mountaintop.

Unsurprisingly, the best song here is one of Prince's own. The title track, with its complicated sense of faith and beautiful lyrics — "You could sit for hours and / only hear the sound of / the trees keeping the lake and sky apart" — is the record's unquestionable peak. Gospel First Nation is a lovely record, one that raises difficult questions without ever asking them directly. It's a document of one man's relationship to family and faith, of reclamation and history and the unknown, suggesting that perhaps everything is connected after all.