Stephen Frears wasn't particularly well known prior to My Beautiful Laundrette. Those within the industry knew him from his work with the BBC and collaborations with some of Britain's most noteworthy directors, but his name didn't mean much in a commercial, or even broadly critical sense. He'd made The Hit, which has since garnered a cult status, but the ferocity and socio-political specificity of Laundrette is what made him a recognizable force in the industry.

As the director notes in the extended interview supplement included with this Criterion Blu-ray release, the project was, at least in part, a reaction to the Thatcher administration. In the early '80s, the sort of neo-liberal Reaganomics that Thatcher fostered — creating jobs and a resulting consumer culture despite tearing down established industry and creating unemployment in different sectors — change the socio-economic climate of England and is, in many ways, still visible today. My Beautiful Laundrette is about people from different classes and cultures operating within the vacuum; some fighting it while others embrace it.

In larger part, the preoccupation of Laundrette within this political climate is the struggle of Asian immigrants. Though the film is primarily about Omar (Gordon Warnecke), the impetus behind his change and his actions stems from the experiences of the generation preceding him, as represented by his father, Hussein (Roshan Seth), and uncle, Nasser (Saeed Jaffrey).

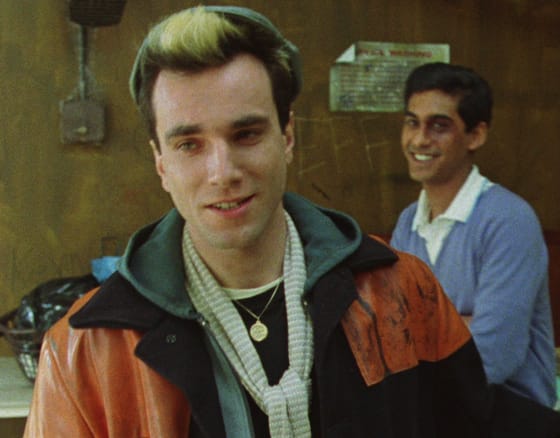

Hussein, a former socialist journalist, has all but given up. His disgust with the monetary preoccupation of his surroundings and the inherent racism of the National Front party have left him a defeated, bed-ridden alcoholic. Nasser, on the other hand, has embraced the opportunity of such a culture, building an empire of blue-collar businesses including the titular laundrette. Where the story starts is with Omar leaving the confines of his father's self-imposed misery to embrace the capitalist enterprise that his uncle offers him. In the periphery, presenting as one of many antagonists, is family relative Salim (Derrick Branche), whose drug-dealing lifestyle has afforded him a countercultural disdain for the lower class white hoodlums, of which Omar's lover Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis) is a part.

What struck people upon Laundrette's release, which was actually a protracted affair, stemming from the underground critical praise it received in the festival circuit, was how it portrayed marginalized people. Almost all of the primary cast were Asian and their struggles, while realist, weren't categorized in a glib or condescending matter. There was nothing particularly politicized about this family drama; it was a grounded portrayal of people trying to reconcile their identity with the culture around them (something consistent throughout the works of Frears, regardless of his refusal to acknowledge auteur status).

It's also interesting that My Beautiful Laundrette didn't tiptoe around the issues at hand, which stems in large part from the authenticity that Hanif Kureishi — who was then unknown, but is now a highly regarded writer — brought to the table. Both Omar and Nasser indulge in affluence to prove something, which is largely represented by their respective decisions to take white people as lovers and subjugate them financially, indirectly making them romantic slaves for survival.

Something else intriguing about this grainy, low-budget pseudo-western drama is its refusal to embrace a firm reality. From the cartoonish soundtrack to the abstract, goofy portrayal of street thugs, there's a contained dreamlike sensibility that permeates every sequence. There's a choreography to everything that makes the building tensions seem less severe. Similarly, the decision to make homosexuality a mere incidental backdrop — something that no one is particularly shocked or upset by — heightens this sense of a constructed reality and contrarian sense of identity.

In the interview with Kureishi included with the Criterion release, he mentions the western backdrop that Frears was toying with throughout the shoot. The manner in which the eventual showdown fizzles beneath the surface of the many underlying tensions building as the characters come closer together is very much suggestive of this construct. Because of this stylistic decision, the lack of catharsis — despite the happy ending — is notable. Though Johnny has a Clint Eastwood demeanour (in a gay hustler sort of way), the attempts he makes with Omar to normalize the many cross-cultural tensions never truly succeed. After the credits roll, the villains are all still there creating the same sort of problems that exist throughout the film. This decision to embrace the familiar only to subtly deny its full potential is something consistent throughout the works of Frears, who is at his best when telling the stories of people existing in conditions out of their element.

As Laundrette was converted from 16mm, it's still quite grainy despite the many technological upgrades of a Criterion release. Similarly, the supplements are strictly those of interviews with key members. While all of this does provide some wonderful insights into the film, it is a tad lacking overall as a package from a distributor that usually has oodles of supplements beyond what one might often imagine.

(Criterion)As the director notes in the extended interview supplement included with this Criterion Blu-ray release, the project was, at least in part, a reaction to the Thatcher administration. In the early '80s, the sort of neo-liberal Reaganomics that Thatcher fostered — creating jobs and a resulting consumer culture despite tearing down established industry and creating unemployment in different sectors — change the socio-economic climate of England and is, in many ways, still visible today. My Beautiful Laundrette is about people from different classes and cultures operating within the vacuum; some fighting it while others embrace it.

In larger part, the preoccupation of Laundrette within this political climate is the struggle of Asian immigrants. Though the film is primarily about Omar (Gordon Warnecke), the impetus behind his change and his actions stems from the experiences of the generation preceding him, as represented by his father, Hussein (Roshan Seth), and uncle, Nasser (Saeed Jaffrey).

Hussein, a former socialist journalist, has all but given up. His disgust with the monetary preoccupation of his surroundings and the inherent racism of the National Front party have left him a defeated, bed-ridden alcoholic. Nasser, on the other hand, has embraced the opportunity of such a culture, building an empire of blue-collar businesses including the titular laundrette. Where the story starts is with Omar leaving the confines of his father's self-imposed misery to embrace the capitalist enterprise that his uncle offers him. In the periphery, presenting as one of many antagonists, is family relative Salim (Derrick Branche), whose drug-dealing lifestyle has afforded him a countercultural disdain for the lower class white hoodlums, of which Omar's lover Johnny (Daniel Day-Lewis) is a part.

What struck people upon Laundrette's release, which was actually a protracted affair, stemming from the underground critical praise it received in the festival circuit, was how it portrayed marginalized people. Almost all of the primary cast were Asian and their struggles, while realist, weren't categorized in a glib or condescending matter. There was nothing particularly politicized about this family drama; it was a grounded portrayal of people trying to reconcile their identity with the culture around them (something consistent throughout the works of Frears, regardless of his refusal to acknowledge auteur status).

It's also interesting that My Beautiful Laundrette didn't tiptoe around the issues at hand, which stems in large part from the authenticity that Hanif Kureishi — who was then unknown, but is now a highly regarded writer — brought to the table. Both Omar and Nasser indulge in affluence to prove something, which is largely represented by their respective decisions to take white people as lovers and subjugate them financially, indirectly making them romantic slaves for survival.

Something else intriguing about this grainy, low-budget pseudo-western drama is its refusal to embrace a firm reality. From the cartoonish soundtrack to the abstract, goofy portrayal of street thugs, there's a contained dreamlike sensibility that permeates every sequence. There's a choreography to everything that makes the building tensions seem less severe. Similarly, the decision to make homosexuality a mere incidental backdrop — something that no one is particularly shocked or upset by — heightens this sense of a constructed reality and contrarian sense of identity.

In the interview with Kureishi included with the Criterion release, he mentions the western backdrop that Frears was toying with throughout the shoot. The manner in which the eventual showdown fizzles beneath the surface of the many underlying tensions building as the characters come closer together is very much suggestive of this construct. Because of this stylistic decision, the lack of catharsis — despite the happy ending — is notable. Though Johnny has a Clint Eastwood demeanour (in a gay hustler sort of way), the attempts he makes with Omar to normalize the many cross-cultural tensions never truly succeed. After the credits roll, the villains are all still there creating the same sort of problems that exist throughout the film. This decision to embrace the familiar only to subtly deny its full potential is something consistent throughout the works of Frears, who is at his best when telling the stories of people existing in conditions out of their element.

As Laundrette was converted from 16mm, it's still quite grainy despite the many technological upgrades of a Criterion release. Similarly, the supplements are strictly those of interviews with key members. While all of this does provide some wonderful insights into the film, it is a tad lacking overall as a package from a distributor that usually has oodles of supplements beyond what one might often imagine.