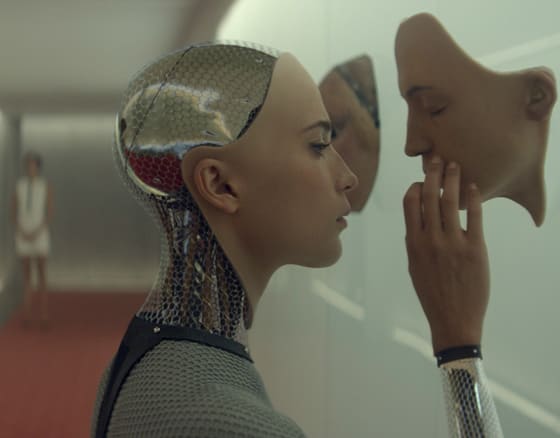

Alex Garland's directorial debut, Ex Machina, is a logical stepping-stone for the psychologically inclined science fiction writer. Though superficially it's about the application of Artificial Intelligence — much in the way that Never Let Me Go was about cloning or Sunshine was about saving the planet — the themes of isolation, alienation and base annihilation anxiety as key to understanding the human condition are prevalent throughout his work. As such, the premise — wherein Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) is ostensibly removed from society to assess the consciousness of Ava (Alicia Vikander), a fully operational female A.I. developed by Nathan (Oscar Isaac), a reclusive billionaire — is consistent with his voice.

From the outset, the world-encompassing Ex Machina is limited and controlled. After winning a workplace lottery, of sorts, Caleb is brought by helicopter to Nathan's underground research complex where the search engine magnate lives alone with mute servant Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno), drinking himself into a stupor every night and working out obsessively every morning.

Garland's tone is perpetually foreboding. Even when Caleb wins the lottery, it's not presented as an exciting moment; it's muted, subdued and reflective. There's an abundance of clean, empty space in each scene and a lot of opportunity for the score to build momentum and the actors to demonstrate a range of contradictory emotions, which is why the little hiccups — an unnecessarily threatening non-disclosure contract, a tendency for the power to cut at the research facility and Nathan's lack of interest in Caleb taking an analytical approach to assessing Ava — raise so many red flags. As an audience, we're constantly scrutinizing Nathan's words and behaviours and trying to determine what's really going on with Ava, particularly when she reveals far more consciousness and capability than he's seemingly aware of.

Emotionally, Ex Machina is entirely successful. It's an engrossing journey that effectively builds a palpable sense of dread and maintains a compelling tone throughout. But what's more interesting are the psychological and sociological discussion points that Garland raises in the periphery.

Obviously, the main discussion is the potential danger of developing a functional artificial intelligence. The text works as a fairly standard admonition in the tradition of science fiction explorations of technological advancement, but there's more than that. It's not arbitrary that Nathan owns a Google-like enterprise and has access to information throughout the world; it's even mentioned early on that he utilized a back door component of mobile devices throughout the world to help develop Ava's speech and facial expression complexity. Beyond the danger of developing A.I. that could technically make the Terminator movies into a reality, there's also some dialogue about the application of modern surveillance and intelligence techniques (something particularly topical). Ex Machina is just as much a cautionary tale about the dangers of giving up privacy for modern conveniences.

Garland is also very interested in the psychological component of Nathan's experiment: How does Ava perceive Caleb? What do isolation and a potentially volatile environment do to Caleb? What does a God complex mean for Nathan? How does Caleb interpret Ava's sexual curiosity? Does she genuinely have feelings for him or is she manipulating him? These are all questions that make these character exchanges and interplay fascinating. If there's a flaw, it's that Caleb's transformation is a tad too dramatic for the one-week timeline, but this doesn't hinder the effectiveness of the narrative build-up and eventual payoff.

It's also true that some of the more complex analytical talking points are muted and glossed over for the sake of appealing to a populist audience. They aren't sacrificed — they're there — but Ex Machina is (effectively) balancing the needs of a general audience with the curiosities of a shrewder viewer. Some minor risks are taken — mostly with the score from Portishead's Geoff Barrow and composer Ben Salisbury — but for every intriguing question brought up, there's an effort to maintain the tone and trajectory of a highly competent thriller template.

Regardless, this clever, claustrophobic, sci-fi psychological horror is a cut above most. It's refreshing to be entertained by a movie that doesn't feel the need to patronize and placate the viewer.

(Mongrel Media)From the outset, the world-encompassing Ex Machina is limited and controlled. After winning a workplace lottery, of sorts, Caleb is brought by helicopter to Nathan's underground research complex where the search engine magnate lives alone with mute servant Kyoko (Sonoya Mizuno), drinking himself into a stupor every night and working out obsessively every morning.

Garland's tone is perpetually foreboding. Even when Caleb wins the lottery, it's not presented as an exciting moment; it's muted, subdued and reflective. There's an abundance of clean, empty space in each scene and a lot of opportunity for the score to build momentum and the actors to demonstrate a range of contradictory emotions, which is why the little hiccups — an unnecessarily threatening non-disclosure contract, a tendency for the power to cut at the research facility and Nathan's lack of interest in Caleb taking an analytical approach to assessing Ava — raise so many red flags. As an audience, we're constantly scrutinizing Nathan's words and behaviours and trying to determine what's really going on with Ava, particularly when she reveals far more consciousness and capability than he's seemingly aware of.

Emotionally, Ex Machina is entirely successful. It's an engrossing journey that effectively builds a palpable sense of dread and maintains a compelling tone throughout. But what's more interesting are the psychological and sociological discussion points that Garland raises in the periphery.

Obviously, the main discussion is the potential danger of developing a functional artificial intelligence. The text works as a fairly standard admonition in the tradition of science fiction explorations of technological advancement, but there's more than that. It's not arbitrary that Nathan owns a Google-like enterprise and has access to information throughout the world; it's even mentioned early on that he utilized a back door component of mobile devices throughout the world to help develop Ava's speech and facial expression complexity. Beyond the danger of developing A.I. that could technically make the Terminator movies into a reality, there's also some dialogue about the application of modern surveillance and intelligence techniques (something particularly topical). Ex Machina is just as much a cautionary tale about the dangers of giving up privacy for modern conveniences.

Garland is also very interested in the psychological component of Nathan's experiment: How does Ava perceive Caleb? What do isolation and a potentially volatile environment do to Caleb? What does a God complex mean for Nathan? How does Caleb interpret Ava's sexual curiosity? Does she genuinely have feelings for him or is she manipulating him? These are all questions that make these character exchanges and interplay fascinating. If there's a flaw, it's that Caleb's transformation is a tad too dramatic for the one-week timeline, but this doesn't hinder the effectiveness of the narrative build-up and eventual payoff.

It's also true that some of the more complex analytical talking points are muted and glossed over for the sake of appealing to a populist audience. They aren't sacrificed — they're there — but Ex Machina is (effectively) balancing the needs of a general audience with the curiosities of a shrewder viewer. Some minor risks are taken — mostly with the score from Portishead's Geoff Barrow and composer Ben Salisbury — but for every intriguing question brought up, there's an effort to maintain the tone and trajectory of a highly competent thriller template.

Regardless, this clever, claustrophobic, sci-fi psychological horror is a cut above most. It's refreshing to be entertained by a movie that doesn't feel the need to patronize and placate the viewer.