Maggie Rogers never asked to be put on a pedestal. But, like with most pop stars, once her music began resonating with fans all over the world, those fans started looking to her for spiritual guidance.

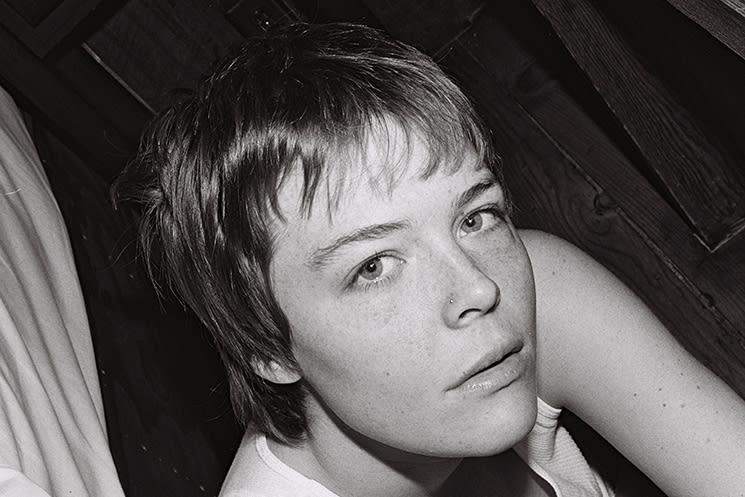

"There was definitely a time in my career where I wanted to be able to help," Rogers tells Exclaim! from New York City over Zoom. (Perhaps that time coincided with when she sold merch that depicted her as one of the Magi.) "I think maybe the greatest lesson is, you can't help anyone else until you help yourself and can't be everything to everyone," she says, easily modulating between earnest conviction and letting throaty laughter burst forth in constellations doubled by her freckles. "The place where I'm coming to now, I feel a lot more relaxed, I think, because I'm just being like, 'I don't know.'"

That may not have been what she went to grad school to figure out, but it seems to have helped regardless. Burned out from many months of touring before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Rogers was craving structure. In 2021, she enrolled in the pilot year of Harvard Divinity School's Religion and Public Life graduate program and recently earned her certificate, fulfilling part of the degree requirement with her performance at this year's Coachella.

"Live music is the most spiritual thing in the world to me," she says, and while studies show that practicing religion in a traditional sense has become increasingly less common, she knows that people are seeking a sense of belief now more than ever — and they often look to musicians to find it.

Rogers herself is no exception: "I'm such a music fan, and have always been a fan first, so I look to artists in the same way," she explains, echoing an aching lament for the loss of David Bowie at the frenetic crux of "Shatter," from her forthcoming sophomore album, Surrender, out tomorrow (July 29) on Capitol Records.

"I take the responsibility of the stage really seriously," she says. "I grew up in a super rural area where I had to travel really far to see music," noting that, coming from a non-musical family, it's always been something she's had to fight for.

"I think that what artists do is feel really deeply," she continues, noting the sense of being overwhelmed by "so much feeling in the world right now and so much to feel about the world right now" elsewhere in our conversation. The radical vulnerability of creating and performing often acts as a vehicle for audiences to access their own emotions; musicians give us permission and embolden us to express ourselves in their mirror image.

But it's a two-way mirror: "It's a very classic songwriting trope that the most personal is the most universal," Rogers offers. "And in that way, I feel a sense of community. I feel connection because I write about my most personal and intimate feelings, and then when someone says, 'I've felt that way, too,' it means that my experience is human and that I wasn't alone in feeling like the world was fucked." And that's the groundwork for peace — both within one's own consciousness and in the world at large, which closing track "Different Kind of World" is a plea for.

If making the album was world-building, her work in grad school was about how to bring the world she'd built out into the world at large. (The parallels surely aren't lost on her — her new album shares its title with her Master's thesis.)

"A lot of what I was doing at school was about sort of preparing to reenter the public sphere or preparing to release the record," she tells me of the musical and scholarly companion pieces. The former was "a lot of thinking about how to bring people together and what I think the ethics of that power is and the responsibility of artists," she says, having deeply considered the boundaries necessary to protect the sanctity of making art.

In what has become the central piece of the myth of Maggie Rogers, the Maryland native shot to viral fame in 2016 after a video of Pharrell Williams's awestruck reaction to an early demo of her song "Alaska" in an NYU masterclass, landing her a major label deal. That song got its lightning-in-a-bottle moment, but it took her the majority of her undergraduate degree to write. Even in the pressure cooker of the pop machine, Rogers has continued to defy the demands of an audience primed for instant gratification by taking until January 2019 to release Heard It in a Past Life. She knew they'd wait.

The new record seems to pick up precisely where its predecessor left off, answering the call of final track "Back in My Body" — so as to foreshadow her next move; as if she knew all of this was coming. Three years on from an album about past lives and she's more grounded in the present moment than ever.

That sense of physicality is Surrender's driving force. The larger-than-life, oil-slick grit of changeling lead single "That's Where I Am" immediately showed new teeth — a repeated image throughout the album — in Rogers. "There [are] these big drums and distorted guitars because I needed frequency that could shock me back into my body," she says, recounting being overcome by numbness amid "so much dystopia." She found comfort in distortion as a chaos she could control, having never experimented with it before because, she says, it didn't feel accessible to her as a woman.

This was the singer-songwriter's response to the softness that marked many comfort-forward early pandemic releases, which made her miss the experience of being a fan, beer-drunk at a British music festival. "I was, like, fiending for feeling the bass in my collarbones," Rogers says, and that hunger helped her unlock a darker sonic palette at times worlds away from her airy, free-flowing debut.

Going to grad school when most of the record had already been recorded (between her parents' garage in Maine, Peter Gabriel's Real World Studios in the English countryside and Electric Lady in NYC) also made her realize that the world she'd built was missing something. "It was just this weird hang-up," Rogers recalls, having been haunted by the sense that the B-side – the half of the record that is ironically more about questioning than the declaratory statements of its counterpart — needed one more track. On her Thanksgiving break, she found it in "Honey."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the song sums up her biggest takeaway from studying religion: if she knew the answer, she'd tell you.

"These are all systems to organize the chaos of the world, and to find a sense of calm within it and reason behind it," she says of spiritual practices, "but at the end of the day, there's literally no answer."

And she's finding a greater sense of ease beneath cloud of unknowing. "Joy is an act of rebellion or resistance in a time that continues to ask us to make ourselves smaller," she says, more assured in both what is and is not her responsibility as an artist. "Like, this is what I believe in," Rogers shrugs. The rest is up to you.

"There was definitely a time in my career where I wanted to be able to help," Rogers tells Exclaim! from New York City over Zoom. (Perhaps that time coincided with when she sold merch that depicted her as one of the Magi.) "I think maybe the greatest lesson is, you can't help anyone else until you help yourself and can't be everything to everyone," she says, easily modulating between earnest conviction and letting throaty laughter burst forth in constellations doubled by her freckles. "The place where I'm coming to now, I feel a lot more relaxed, I think, because I'm just being like, 'I don't know.'"

That may not have been what she went to grad school to figure out, but it seems to have helped regardless. Burned out from many months of touring before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Rogers was craving structure. In 2021, she enrolled in the pilot year of Harvard Divinity School's Religion and Public Life graduate program and recently earned her certificate, fulfilling part of the degree requirement with her performance at this year's Coachella.

"Live music is the most spiritual thing in the world to me," she says, and while studies show that practicing religion in a traditional sense has become increasingly less common, she knows that people are seeking a sense of belief now more than ever — and they often look to musicians to find it.

Rogers herself is no exception: "I'm such a music fan, and have always been a fan first, so I look to artists in the same way," she explains, echoing an aching lament for the loss of David Bowie at the frenetic crux of "Shatter," from her forthcoming sophomore album, Surrender, out tomorrow (July 29) on Capitol Records.

"I take the responsibility of the stage really seriously," she says. "I grew up in a super rural area where I had to travel really far to see music," noting that, coming from a non-musical family, it's always been something she's had to fight for.

"I think that what artists do is feel really deeply," she continues, noting the sense of being overwhelmed by "so much feeling in the world right now and so much to feel about the world right now" elsewhere in our conversation. The radical vulnerability of creating and performing often acts as a vehicle for audiences to access their own emotions; musicians give us permission and embolden us to express ourselves in their mirror image.

But it's a two-way mirror: "It's a very classic songwriting trope that the most personal is the most universal," Rogers offers. "And in that way, I feel a sense of community. I feel connection because I write about my most personal and intimate feelings, and then when someone says, 'I've felt that way, too,' it means that my experience is human and that I wasn't alone in feeling like the world was fucked." And that's the groundwork for peace — both within one's own consciousness and in the world at large, which closing track "Different Kind of World" is a plea for.

If making the album was world-building, her work in grad school was about how to bring the world she'd built out into the world at large. (The parallels surely aren't lost on her — her new album shares its title with her Master's thesis.)

"A lot of what I was doing at school was about sort of preparing to reenter the public sphere or preparing to release the record," she tells me of the musical and scholarly companion pieces. The former was "a lot of thinking about how to bring people together and what I think the ethics of that power is and the responsibility of artists," she says, having deeply considered the boundaries necessary to protect the sanctity of making art.

In what has become the central piece of the myth of Maggie Rogers, the Maryland native shot to viral fame in 2016 after a video of Pharrell Williams's awestruck reaction to an early demo of her song "Alaska" in an NYU masterclass, landing her a major label deal. That song got its lightning-in-a-bottle moment, but it took her the majority of her undergraduate degree to write. Even in the pressure cooker of the pop machine, Rogers has continued to defy the demands of an audience primed for instant gratification by taking until January 2019 to release Heard It in a Past Life. She knew they'd wait.

The new record seems to pick up precisely where its predecessor left off, answering the call of final track "Back in My Body" — so as to foreshadow her next move; as if she knew all of this was coming. Three years on from an album about past lives and she's more grounded in the present moment than ever.

That sense of physicality is Surrender's driving force. The larger-than-life, oil-slick grit of changeling lead single "That's Where I Am" immediately showed new teeth — a repeated image throughout the album — in Rogers. "There [are] these big drums and distorted guitars because I needed frequency that could shock me back into my body," she says, recounting being overcome by numbness amid "so much dystopia." She found comfort in distortion as a chaos she could control, having never experimented with it before because, she says, it didn't feel accessible to her as a woman.

This was the singer-songwriter's response to the softness that marked many comfort-forward early pandemic releases, which made her miss the experience of being a fan, beer-drunk at a British music festival. "I was, like, fiending for feeling the bass in my collarbones," Rogers says, and that hunger helped her unlock a darker sonic palette at times worlds away from her airy, free-flowing debut.

Going to grad school when most of the record had already been recorded (between her parents' garage in Maine, Peter Gabriel's Real World Studios in the English countryside and Electric Lady in NYC) also made her realize that the world she'd built was missing something. "It was just this weird hang-up," Rogers recalls, having been haunted by the sense that the B-side – the half of the record that is ironically more about questioning than the declaratory statements of its counterpart — needed one more track. On her Thanksgiving break, she found it in "Honey."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the song sums up her biggest takeaway from studying religion: if she knew the answer, she'd tell you.

"These are all systems to organize the chaos of the world, and to find a sense of calm within it and reason behind it," she says of spiritual practices, "but at the end of the day, there's literally no answer."

And she's finding a greater sense of ease beneath cloud of unknowing. "Joy is an act of rebellion or resistance in a time that continues to ask us to make ourselves smaller," she says, more assured in both what is and is not her responsibility as an artist. "Like, this is what I believe in," Rogers shrugs. The rest is up to you.