Is this Sufjan Stevens album gay, or about God — or is it grief? The answer is, as devoted fans have unspokenly known for decades, all of the above. His most vulnerable work of art since 2015's Carrie & Lowell, Stevens's 10th studio album Javelin is dedicated to his late partner Evans Richardson, who died six months prior to its release. With this dedication came Stevens's first public recognition of his romantic proclivities; his unconfirmed queerness has always been at the heart of his most cherished works, but that extra bit of representation is all the more devastating given the context.

That's all unbelievably bittersweet, but to make matters worse, the singer-songwriter became hospitalized with a rare autoimmune disorder the summer before Javelin's release. He would later go on to recognize himself as a sort of "poster child of pain, loss, and loneliness" amid all the suffering. An understatement.

Even still, he remains a beacon of light among listeners, followers of his lone internet transmissions (on Tumblr, no less), music critics and fellow musicians. Nearing a quarter-century into his career, Stevens is arguably among his generation's best songwriters, spanning multiple genres over his sprawling catalogue, trying on electronic, folk, pop, classical and the savoury bits betwixt like one of his many signature teetering baseball hats — always pulling it off despite how goofy it might appear to the unindoctrinated. His catalogue, with its early-millennium pioneering baroque pop and twee, is proof of both an adaptation strategy from an artist who began his career all the way back in the late '90s, and his enduring creative curiosity.

The enormity of these influences coalesces in Javelin, a record whose weight often feels like a bookend, the final gasp of a tired soul's plea to the forces that be — giving in without giving up. Before the world at large learned of Richardson's passing, critics assumed that Stevens was about to deliver a breakup album, having launched the collection with "So You Are Tired" and following up with "Will Anybody Ever Love Me?" He sings in the former's final verse, "So you are tired of me / So rest your head / Turning back all that we had in our life / While I return to death," whereas he sings, "Chase away my heart and heartache / Run me over, throw me over, cast me out," in the latter's opening, before begging for love without grievance. Misdirects? Maybe.

But heartrending all the same. Stevens uttered similar appeals to higher powers on 2020's apocalyptic The Ascension, during an era in which he described himself as an "artist of particulars, specificities and the minutia" and revealed that he was done making music for at least five years. (We know better by now than to assume Stevens will ever be done with us; since he promised that break, he's released four albums.) It's that dichotomy — of a sensitive creative's attention to the art of being, and simultaneously wanting to "cast" himself out — that creates such dynamic records. He can be soft. He can be loud. Angry, heartbroken, ashamed, proud. He can be all at once. And yet, we'll never know for sure how much of the album is informed by his life's recent tragedies.

Part of that comes from being a purposefully elusive songwriter, a skill no doubt honed over the years to further obfuscate his private life. Javelin finds Stevens at his most vulnerable, yes, but like Carrie & Lowell, he paradoxically hides behind a wall of references and metaphor (many of which I'm sure are biblical in nature, discreetly whizzing past my woefully secular ears). Now posited in plainer language than ever before, he makes its cipher even more challenging to crack. That's what makes these records so healing to their audiences, though: the universality. It's that element that conversely begs for the album's backstory to fade from its identity over time. Stevens himself is practically asking for time to forget on both our behalf and his.

Fittingly, the album's opening track, "Goodbye Evergreen," appeals to a broad sense of angst: "I'm drowning in my self-defence / Now punish me," Stevens sings, before ending the verse, "Pressed out in the rain / Deliver me from the poison pain." The choral singing (props to guest vocalists Megan Lui, Hannah Cohen, Pauline Delassus, Nedelle Torrisi and adrienne maree brown), whimsical flute, atmospheric strings, the anxious, building, shattered synths — it's all emblematic of Stevens's unique talent for introductions. (He's probably great at parties!)

That luminosity is the counterpart to another of the multifaceted artist's alter egos: that which plucks on guitar strings like a harp-bearing angel descending from the skies. Conjuring the choral accompaniment of Illinois, the quaint imagery of Michigan and the deceptively complex arrangements of Seven Swans, track two, the hopelessly hopeful "A Running Start," turns its head from the sharpness of its prelude, instead asking gently for a kiss — a request repeated in vain throughout the record with greater pain upon each delivery.

Javelin's most lyrically potent tracks are perhaps also its sleepers: "Genuflecting Ghost," "My Red Little Fox" and "Shit Talk" each represent Stevens at his songwriting best. "Fox," in particular, is instrumentally sparse, with its words alluding to a yearning tug-of-war. Our narrator, desiring a union ("Don't start with your camouflage"); his sparrer, imbued with defiant respiratory essence Stevens wishes to harness ("Kiss me like the wind that flows within your veins"), are in a one-sided battle. "Shit Talk" finds the same narrator more in a fighting mood — and Stevens is empowered to win here, with the song's eight-minute runtime bolstering his attack: "Our romantic second chance is dead / I buried it with the hatchet / Quit your antics / Put them at the foot of the bed / And set it on fire."

The album largely finds Stevens between worlds, a vessel for the apparition, which is where his work is most vital — when he outstretches an arm along the astral plane as if to vandalize it with his otherworldly observations and complaints. The minutia deployed in the historical footnotes of his abandoned 50 states project, in romanticizing the planets of our solar system, the Chinese zodiac, classic cinema, Christmas and other such external influences are, of course, among his best work — but it's these more personal meditations where he is at his most affecting and ageless. In going inward over the years, he has created space for those grieving the death of a parent, those questioning the purpose of existence in the face of apocalypse, those wrestling with their faith, with whom they love, and ultimately with the loss of that love.

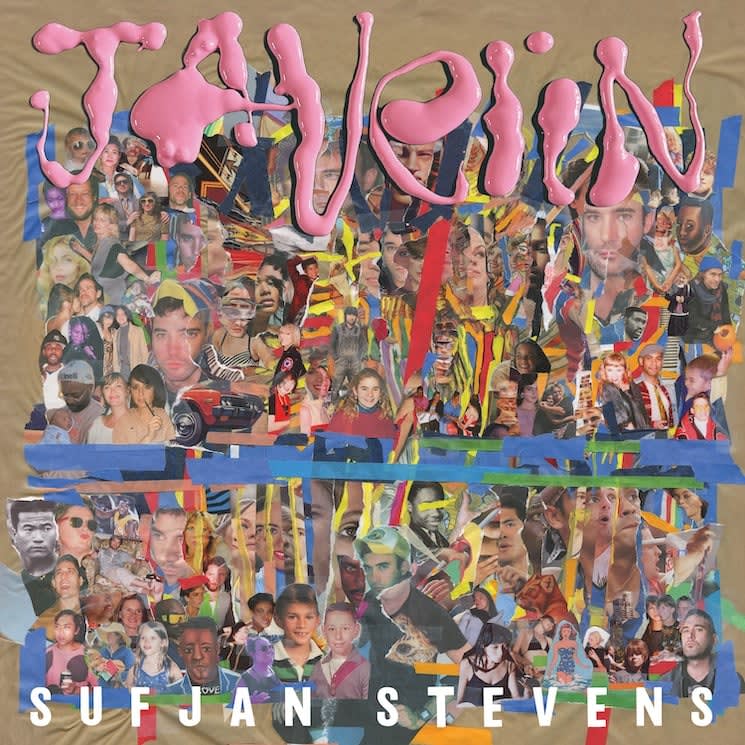

(Asthmatic Kitty)That's all unbelievably bittersweet, but to make matters worse, the singer-songwriter became hospitalized with a rare autoimmune disorder the summer before Javelin's release. He would later go on to recognize himself as a sort of "poster child of pain, loss, and loneliness" amid all the suffering. An understatement.

Even still, he remains a beacon of light among listeners, followers of his lone internet transmissions (on Tumblr, no less), music critics and fellow musicians. Nearing a quarter-century into his career, Stevens is arguably among his generation's best songwriters, spanning multiple genres over his sprawling catalogue, trying on electronic, folk, pop, classical and the savoury bits betwixt like one of his many signature teetering baseball hats — always pulling it off despite how goofy it might appear to the unindoctrinated. His catalogue, with its early-millennium pioneering baroque pop and twee, is proof of both an adaptation strategy from an artist who began his career all the way back in the late '90s, and his enduring creative curiosity.

The enormity of these influences coalesces in Javelin, a record whose weight often feels like a bookend, the final gasp of a tired soul's plea to the forces that be — giving in without giving up. Before the world at large learned of Richardson's passing, critics assumed that Stevens was about to deliver a breakup album, having launched the collection with "So You Are Tired" and following up with "Will Anybody Ever Love Me?" He sings in the former's final verse, "So you are tired of me / So rest your head / Turning back all that we had in our life / While I return to death," whereas he sings, "Chase away my heart and heartache / Run me over, throw me over, cast me out," in the latter's opening, before begging for love without grievance. Misdirects? Maybe.

But heartrending all the same. Stevens uttered similar appeals to higher powers on 2020's apocalyptic The Ascension, during an era in which he described himself as an "artist of particulars, specificities and the minutia" and revealed that he was done making music for at least five years. (We know better by now than to assume Stevens will ever be done with us; since he promised that break, he's released four albums.) It's that dichotomy — of a sensitive creative's attention to the art of being, and simultaneously wanting to "cast" himself out — that creates such dynamic records. He can be soft. He can be loud. Angry, heartbroken, ashamed, proud. He can be all at once. And yet, we'll never know for sure how much of the album is informed by his life's recent tragedies.

Part of that comes from being a purposefully elusive songwriter, a skill no doubt honed over the years to further obfuscate his private life. Javelin finds Stevens at his most vulnerable, yes, but like Carrie & Lowell, he paradoxically hides behind a wall of references and metaphor (many of which I'm sure are biblical in nature, discreetly whizzing past my woefully secular ears). Now posited in plainer language than ever before, he makes its cipher even more challenging to crack. That's what makes these records so healing to their audiences, though: the universality. It's that element that conversely begs for the album's backstory to fade from its identity over time. Stevens himself is practically asking for time to forget on both our behalf and his.

Fittingly, the album's opening track, "Goodbye Evergreen," appeals to a broad sense of angst: "I'm drowning in my self-defence / Now punish me," Stevens sings, before ending the verse, "Pressed out in the rain / Deliver me from the poison pain." The choral singing (props to guest vocalists Megan Lui, Hannah Cohen, Pauline Delassus, Nedelle Torrisi and adrienne maree brown), whimsical flute, atmospheric strings, the anxious, building, shattered synths — it's all emblematic of Stevens's unique talent for introductions. (He's probably great at parties!)

That luminosity is the counterpart to another of the multifaceted artist's alter egos: that which plucks on guitar strings like a harp-bearing angel descending from the skies. Conjuring the choral accompaniment of Illinois, the quaint imagery of Michigan and the deceptively complex arrangements of Seven Swans, track two, the hopelessly hopeful "A Running Start," turns its head from the sharpness of its prelude, instead asking gently for a kiss — a request repeated in vain throughout the record with greater pain upon each delivery.

Javelin's most lyrically potent tracks are perhaps also its sleepers: "Genuflecting Ghost," "My Red Little Fox" and "Shit Talk" each represent Stevens at his songwriting best. "Fox," in particular, is instrumentally sparse, with its words alluding to a yearning tug-of-war. Our narrator, desiring a union ("Don't start with your camouflage"); his sparrer, imbued with defiant respiratory essence Stevens wishes to harness ("Kiss me like the wind that flows within your veins"), are in a one-sided battle. "Shit Talk" finds the same narrator more in a fighting mood — and Stevens is empowered to win here, with the song's eight-minute runtime bolstering his attack: "Our romantic second chance is dead / I buried it with the hatchet / Quit your antics / Put them at the foot of the bed / And set it on fire."

The album largely finds Stevens between worlds, a vessel for the apparition, which is where his work is most vital — when he outstretches an arm along the astral plane as if to vandalize it with his otherworldly observations and complaints. The minutia deployed in the historical footnotes of his abandoned 50 states project, in romanticizing the planets of our solar system, the Chinese zodiac, classic cinema, Christmas and other such external influences are, of course, among his best work — but it's these more personal meditations where he is at his most affecting and ageless. In going inward over the years, he has created space for those grieving the death of a parent, those questioning the purpose of existence in the face of apocalypse, those wrestling with their faith, with whom they love, and ultimately with the loss of that love.