Often considered the greatest band to ever emerge from the country of Wales, Manic Street Preachers have lived as many lives as they've released albums in their 30-year history. In the beginning, they were brazen anarchists caked in makeup and draped in leopard print, declaring they hated Slowdive "more than Hitler" and that they'd sell 16 million copies of their debut and then break up. When NME journalist Steve Lamacq called them out as posers, guitarist Richey James Edwards took a razor and hacked "4 REAL" into his arm [NSFW].

The Manics learned to evolve, shedding their bombastic glam image to become a voice for the everyman. They disguised their intensely cerebral, political and personal music as penetrating anthems, which turned them into one of the UK's biggest bands over the last two decades.

Their success, however, came with a turn of fate. In February 1995, Edwards, who was struggling with severe depression and bouts of self-harm, disappeared without a trace. As one of the band's two lyricists and the main architect of 1994's The Holy Bible, the loss was as devastating professionally as it was personally. Instead of packing it in or filling the hole, remaining members James Dean Bradfield, Sean Moore and Nicky Wire continued as a trio out of respect for their lost brother, and their comeback album, 1996's mature Everything Must Go, was an absolute triumph both critically and commercially.

Across the subsequent albums, the Manics would continuously refuse to buck trends in order to revolutionize their music, from the adult alternative This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours to the "post-punk disco-rock" of Futurology.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Everything Must Go, which the band are commemorating with a special edition reissue and a European tour performing the album in full. On top of that, the Manics are also backing the Welsh football team for its run in Euro 2016 with a commissioned anthem called "Together Stronger (C'mon Wales)."

With all of this in mind, here's Exclaim!'s Essential Guide to Manic Street Preachers.

Essential Albums:

5. Send Away the Tigers

(2007)

After two disappointing releases — the politically abrasive Know Your Enemy and the sophisti-pop-leaning Lifeblood — the Manics were in need of another refresh. Solo albums by Bradfield and Wire helped get the band's songwriting back on track, but it was their decision to begin writing more loudly and anthemic again that made Send Away the Tigers such a return to form. Going with impulse over deliberation, the Manics let their inhibitions go to strike a fine balance between the glam rock riffage of Generation Terrorists and the poignant songwriting of Everything Must Go.

Clocking in at a concise 38 minutes, Tigers brims with confidence and more beefy hooks than ever, best exemplified by the sweeping melodies of "Autumnsong," the rollicking chug of "Underdogs" and the pure pop prowess of Bradfield's buoyant duet with the Cardigans' Nina Persson, "Your Love Alone Is Not Enough." Tigers is the sound of the Manics discovering the joy of making records again after suffering something of a creative slump.

4. Futurology

(2014)

Few bands survive to make a 12th album, and even fewer bands have the creative juices to make it one of their best. But the Manics didn't just turn in one of their best efforts 28 years into their career; they also turned in their most audacious effort to date.

Futurology arrived as a companion to Rewind the Film just nine months later, but it presented a far more radical vision. Where Rewind was, according to Wire, "a harrowing 45-year-old looking in the mirror," Futurology was a restless album exploring "the idea that any kind of art can transport you to a different universe." Here were the Manics taking bold creative leaps, throwing out a disco-rock stomper sung in half-German ("Europa Geht Durch Mich"), a Krautrock banger ("The Next Jet to Leave Moscow") and a prog odyssey named after an early 20th century Russian poet ("Mayakovsky"), like a band with nothing to lose.

3. Journal for Plague Lovers

(2009)

Go figure — the Manics followed the stadium-ready rock of Send Away the Tigers with a relentlessly exploratory piece of art rock. The band felt it was important to use Richey's remaining lyrics as a way of finding closure, and as such, Journal for Plague Lovers feels like a heartfelt tribute to their late guitarist. Released without any commercial singles, it continued the darker lyrical themes that Richey explored on The Holy Bible, so it came as no surprise when many fans began regarding Journal as a sequel to their 1994 classic.

Steve Albini was a wise choice to engineer the majority of the tracks, as he wrapped these songs in barbed wire and gave them the guttural effect they deserved. As an obsessive fan of Nirvana's In Utero, there's no question Richey would have been ecstatic about Albini's involvement.

By exorcising Richey's ghost, the Manics were finally putting the past behind them while adhering to their habit of being fresh and unpredictable. Journal for Plague Lovers is a raw gut punch that somehow achieves accessibility despite its attempts to fight commerciality — just how Richey would have done it.

2. Everything Must Go

(1996)

On their fourth album, the Manic Street Preachers were in search of catharsis — and they found it.

They had to. After mysteriously losing Richey the year before, the remaining band members waited two months before deciding on their future. Few people would have guessed Wire, Bradfield and Moore would make such a triumphant return, but it was impossible not to feel overcome with emotion upon hearing those strings come crashing in on the album's first single, "A Design for Life." Gone were the screaming guitars and distressing lyrics, replaced by magnificent, hopeful modern rock songs — like "No Surface All Feeling" and the moving title track — that were fine-tuned for the masses.

There was a fateful sense of irony in the Manics attaining their commercial breakthrough without Richey by their side, but with Britpop at its peak, fame and success were inevitable. Richey was there in spirit though; he received songwriting credits on five tracks, and it's impossible not to feel his presence on the elegiac "Small Black Flowers That Grow in the Sky."

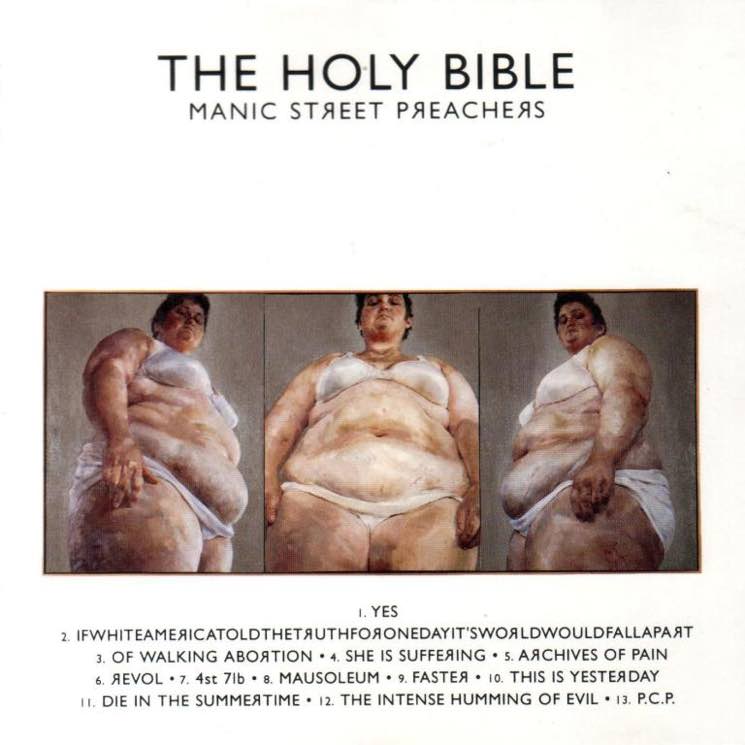

1. The Holy Bible

(1994)

Those who like their pub singalongs will always consider Everything Must Go the Manics' essential album, but in general there's no contest: The Holy Bible is the one. It was the lynchpin of the band's career, reinventing the band after Gold Against the Soul's sullen glam rock left them feeling empty, setting up the resurrection two years later and acting as Richey's farewell letter to the world.

The writing was on the wall with The Holy Bible. This was Richey's album; he wrote three-quarters of the lyrics, which reflected on a range of grim subjects — "prostitution, American consumerism, British imperialism, freedom of speech, the Holocaust, self-starvation, serial killers, the death penalty, political revolution, childhood, fascism and suicide" — that should have immediately raised red flags about his emotional and mental state.

Richey was severely depressed and drinking heavily, spending most of his time in the studio too inebriated to play guitar. His self-harm had also gotten out of control, and he was suffering from anorexia nervosa (at one point his weight dropped to approximately 85 pounds, as documented in "4st 7lbs"). It was all laid out in the album's opening cut, "Yes": "I eat and I dress and I wash and I still can say thank you / Puking, shaking, sinking / Can't shout, can't scream, I hurt myself to get pain out."

The band's decision to assume a violent post-punk sound was an obvious reaction to the traumatizing, caustic lyrics, but also demonstrated just how little they cared about their place in the British music scene at the time. While Britpop was rising (Definitely Maybe was released the same day), the Manics were offering the polar opposite: a bleak, uncompromising work that wanted nothing to do with the party.

It's hard not to get chills hearing Bradfield inhabit Richey's mind and singing about wasting away on "4st 7lbs," but the angular noise that surrounds his voice evokes a sense of comfort in terrifying circumstances.

That goes for just about everything on The Holy Bible. Somehow, the band took some of the most gruesome lyrics ever put to paper and turned them into an intensely captivating album full of unlikely anthems like "Faster," "Yes" and "Revol." As startling as it is to hear, this is the Manics on the brink of collapse — and at their very best.

What to Avoid:

Truth be told, Manic Street Preachers haven't experienced the artistic lows that most musicians have suffered. That might sound like a copout, but it's hard to really single out any of the band's releases that should be avoided; all 12 albums are part of their fascinating narrative.

That said, there are some releases that aren't quite as strong as others. Unfortunately for Gold Against the Soul (1993), it was sandwiched in between the band's outrageous debut and stone cold classic. You can hear the band struggling to find an identity, and it came at an awkward time for the band — they were the supporting act for Bon Jovi on tour circa Keep the Faith. Brushing off the glam image of Generation Terrorists and not quite developed into the paranoid persona of The Holy Bible, the album was a glorified mess that sounded half written for the radio, half written to please fans of wanky guitar solos. Still, it did produce three of the band's best singles: "From Despair to Where," "Roses in the Hospital" and "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)."

Know Your Enemy (2001) suffers because it was an obvious attempt to reclaim the edge they lost after Everything Must Go and This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours. All of a sudden, the Manics were as big as they initially imagined they'd be — adorning their album covers with photos of them decked out in white GAP wear, for example — and they needed to stir the pot again. By releasing the blistering politico-punk single "The Masses Against the Classes," they reclaimed much of their anarcho-spirit, but not enough of that focus spilled over into Know Your Enemy. While it was exciting to hear them be impulsive again, the album was too erratic, uneven and bloated, not to mention it clocked in at a draining 75 minutes.

Originally described by Wire as sounding like "heavy metal Tamla Motown, Van Halen playing The Supremes!," Postcards from a Young Man (2010) could have been another profound reinvention. Alas, Wire's ambition proved too much for the band's abilities and it didn't live up to that promise. The Manics playing it a little too safe — which is understandable, especially coming after the brutally raw Journal for Plague Lovers. It feels a little unfair including Postcards as something to avoid, because it's a well-rounded effort, but against the rest of the catalogue, it doesn't quite measure up.

Further Listening:

Generation Terrorists (1992) has aged about as well as their style — which was all about hairspray, lipstick (everywhere) and spray paint-stencilled clothing — but Manic Street Preachers' debut album remains a lot of fun. Inspired by the gluttony and glam of Guns N' Roses' Appetite for Destruction, Generation Terrorists is full of Slash-inspired solos ("Motorcycle Emptiness"), narcissistic rockers ("You Love Us," "Stay Beautiful") and drugs ("Methadone Pretty"). The fact that it sounds dated is part of its charm — a guest vocal by Traci Lords on "Little Baby Nothing" is deliciously passé. Sure, it didn't go on to sell the 16 million they facetiously predicted, but the Manics fired on all cylinders and delivered everything else they were promising at the time.

Their best-selling album to date, This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours (1998) was the only moment where the Manics decided against changing up their sound. If anything, This Is My Truth delved deeper into the mature sound that Everything Must Go established: the strings were more ostentatious ("The Everlasting"), the rock anthems more anthemic ("You Stole the Sun from My Heart") and the introspective ballads more intimate ("Be a Girl"). And of course, there was the ridiculously named "If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next," which contained a chorus that had no business being infectious, but is anyway.

The most divisive album in the Manics' discography is unquestionably Lifeblood (2004). Both critics and fans — and eventually the band themselves — were lukewarm to the album's polished, soft-edged sound, which bears resemblance to that of both U2 and Coldplay. But seeing as it came after the confusing mess of Know Your Enemy, you can hardly blame them for trying something so easy on the ear. Lifeblood, though, is a fine example of how the Manics can tip the spectrum when they want: this is as opposite to The Holy Bible as it can get. Complaints of being too AOR-friendly were loud and clear, but Lifeblood is deeply misunderstood. The album found the band experimenting with an extravagance they'd never put to tape before, which might have something to do with co-producer Tony Visconti (who, strangely enough, did not produce the Bowie-esque "Always/Never").

Finally there's the mostly acoustic Rewind the Film (2013), and though it often gets overshadowed by its more ambitious companion, Futurology, it's really the yin to that album's yang. Where Futurology was all about pushing their ambition to the max, Rewind the Film was a simpler album that reflect on life as a 40-something. And while it could very well have been a midlife crisis record, Rewind is too lovely and hopeful to deserve that categorization. It's a gorgeously arranged collection of modern pop music that proves the Manics will age gracefully — whenever they're ready to.

The Manics learned to evolve, shedding their bombastic glam image to become a voice for the everyman. They disguised their intensely cerebral, political and personal music as penetrating anthems, which turned them into one of the UK's biggest bands over the last two decades.

Their success, however, came with a turn of fate. In February 1995, Edwards, who was struggling with severe depression and bouts of self-harm, disappeared without a trace. As one of the band's two lyricists and the main architect of 1994's The Holy Bible, the loss was as devastating professionally as it was personally. Instead of packing it in or filling the hole, remaining members James Dean Bradfield, Sean Moore and Nicky Wire continued as a trio out of respect for their lost brother, and their comeback album, 1996's mature Everything Must Go, was an absolute triumph both critically and commercially.

Across the subsequent albums, the Manics would continuously refuse to buck trends in order to revolutionize their music, from the adult alternative This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours to the "post-punk disco-rock" of Futurology.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Everything Must Go, which the band are commemorating with a special edition reissue and a European tour performing the album in full. On top of that, the Manics are also backing the Welsh football team for its run in Euro 2016 with a commissioned anthem called "Together Stronger (C'mon Wales)."

With all of this in mind, here's Exclaim!'s Essential Guide to Manic Street Preachers.

Essential Albums:

5. Send Away the Tigers

(2007)

After two disappointing releases — the politically abrasive Know Your Enemy and the sophisti-pop-leaning Lifeblood — the Manics were in need of another refresh. Solo albums by Bradfield and Wire helped get the band's songwriting back on track, but it was their decision to begin writing more loudly and anthemic again that made Send Away the Tigers such a return to form. Going with impulse over deliberation, the Manics let their inhibitions go to strike a fine balance between the glam rock riffage of Generation Terrorists and the poignant songwriting of Everything Must Go.

Clocking in at a concise 38 minutes, Tigers brims with confidence and more beefy hooks than ever, best exemplified by the sweeping melodies of "Autumnsong," the rollicking chug of "Underdogs" and the pure pop prowess of Bradfield's buoyant duet with the Cardigans' Nina Persson, "Your Love Alone Is Not Enough." Tigers is the sound of the Manics discovering the joy of making records again after suffering something of a creative slump.

4. Futurology

(2014)

Few bands survive to make a 12th album, and even fewer bands have the creative juices to make it one of their best. But the Manics didn't just turn in one of their best efforts 28 years into their career; they also turned in their most audacious effort to date.

Futurology arrived as a companion to Rewind the Film just nine months later, but it presented a far more radical vision. Where Rewind was, according to Wire, "a harrowing 45-year-old looking in the mirror," Futurology was a restless album exploring "the idea that any kind of art can transport you to a different universe." Here were the Manics taking bold creative leaps, throwing out a disco-rock stomper sung in half-German ("Europa Geht Durch Mich"), a Krautrock banger ("The Next Jet to Leave Moscow") and a prog odyssey named after an early 20th century Russian poet ("Mayakovsky"), like a band with nothing to lose.

3. Journal for Plague Lovers

(2009)

Go figure — the Manics followed the stadium-ready rock of Send Away the Tigers with a relentlessly exploratory piece of art rock. The band felt it was important to use Richey's remaining lyrics as a way of finding closure, and as such, Journal for Plague Lovers feels like a heartfelt tribute to their late guitarist. Released without any commercial singles, it continued the darker lyrical themes that Richey explored on The Holy Bible, so it came as no surprise when many fans began regarding Journal as a sequel to their 1994 classic.

Steve Albini was a wise choice to engineer the majority of the tracks, as he wrapped these songs in barbed wire and gave them the guttural effect they deserved. As an obsessive fan of Nirvana's In Utero, there's no question Richey would have been ecstatic about Albini's involvement.

By exorcising Richey's ghost, the Manics were finally putting the past behind them while adhering to their habit of being fresh and unpredictable. Journal for Plague Lovers is a raw gut punch that somehow achieves accessibility despite its attempts to fight commerciality — just how Richey would have done it.

2. Everything Must Go

(1996)

On their fourth album, the Manic Street Preachers were in search of catharsis — and they found it.

They had to. After mysteriously losing Richey the year before, the remaining band members waited two months before deciding on their future. Few people would have guessed Wire, Bradfield and Moore would make such a triumphant return, but it was impossible not to feel overcome with emotion upon hearing those strings come crashing in on the album's first single, "A Design for Life." Gone were the screaming guitars and distressing lyrics, replaced by magnificent, hopeful modern rock songs — like "No Surface All Feeling" and the moving title track — that were fine-tuned for the masses.

There was a fateful sense of irony in the Manics attaining their commercial breakthrough without Richey by their side, but with Britpop at its peak, fame and success were inevitable. Richey was there in spirit though; he received songwriting credits on five tracks, and it's impossible not to feel his presence on the elegiac "Small Black Flowers That Grow in the Sky."

1. The Holy Bible

(1994)

Those who like their pub singalongs will always consider Everything Must Go the Manics' essential album, but in general there's no contest: The Holy Bible is the one. It was the lynchpin of the band's career, reinventing the band after Gold Against the Soul's sullen glam rock left them feeling empty, setting up the resurrection two years later and acting as Richey's farewell letter to the world.

The writing was on the wall with The Holy Bible. This was Richey's album; he wrote three-quarters of the lyrics, which reflected on a range of grim subjects — "prostitution, American consumerism, British imperialism, freedom of speech, the Holocaust, self-starvation, serial killers, the death penalty, political revolution, childhood, fascism and suicide" — that should have immediately raised red flags about his emotional and mental state.

Richey was severely depressed and drinking heavily, spending most of his time in the studio too inebriated to play guitar. His self-harm had also gotten out of control, and he was suffering from anorexia nervosa (at one point his weight dropped to approximately 85 pounds, as documented in "4st 7lbs"). It was all laid out in the album's opening cut, "Yes": "I eat and I dress and I wash and I still can say thank you / Puking, shaking, sinking / Can't shout, can't scream, I hurt myself to get pain out."

The band's decision to assume a violent post-punk sound was an obvious reaction to the traumatizing, caustic lyrics, but also demonstrated just how little they cared about their place in the British music scene at the time. While Britpop was rising (Definitely Maybe was released the same day), the Manics were offering the polar opposite: a bleak, uncompromising work that wanted nothing to do with the party.

It's hard not to get chills hearing Bradfield inhabit Richey's mind and singing about wasting away on "4st 7lbs," but the angular noise that surrounds his voice evokes a sense of comfort in terrifying circumstances.

That goes for just about everything on The Holy Bible. Somehow, the band took some of the most gruesome lyrics ever put to paper and turned them into an intensely captivating album full of unlikely anthems like "Faster," "Yes" and "Revol." As startling as it is to hear, this is the Manics on the brink of collapse — and at their very best.

What to Avoid:

Truth be told, Manic Street Preachers haven't experienced the artistic lows that most musicians have suffered. That might sound like a copout, but it's hard to really single out any of the band's releases that should be avoided; all 12 albums are part of their fascinating narrative.

That said, there are some releases that aren't quite as strong as others. Unfortunately for Gold Against the Soul (1993), it was sandwiched in between the band's outrageous debut and stone cold classic. You can hear the band struggling to find an identity, and it came at an awkward time for the band — they were the supporting act for Bon Jovi on tour circa Keep the Faith. Brushing off the glam image of Generation Terrorists and not quite developed into the paranoid persona of The Holy Bible, the album was a glorified mess that sounded half written for the radio, half written to please fans of wanky guitar solos. Still, it did produce three of the band's best singles: "From Despair to Where," "Roses in the Hospital" and "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)."

Know Your Enemy (2001) suffers because it was an obvious attempt to reclaim the edge they lost after Everything Must Go and This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours. All of a sudden, the Manics were as big as they initially imagined they'd be — adorning their album covers with photos of them decked out in white GAP wear, for example — and they needed to stir the pot again. By releasing the blistering politico-punk single "The Masses Against the Classes," they reclaimed much of their anarcho-spirit, but not enough of that focus spilled over into Know Your Enemy. While it was exciting to hear them be impulsive again, the album was too erratic, uneven and bloated, not to mention it clocked in at a draining 75 minutes.

Originally described by Wire as sounding like "heavy metal Tamla Motown, Van Halen playing The Supremes!," Postcards from a Young Man (2010) could have been another profound reinvention. Alas, Wire's ambition proved too much for the band's abilities and it didn't live up to that promise. The Manics playing it a little too safe — which is understandable, especially coming after the brutally raw Journal for Plague Lovers. It feels a little unfair including Postcards as something to avoid, because it's a well-rounded effort, but against the rest of the catalogue, it doesn't quite measure up.

Further Listening:

Generation Terrorists (1992) has aged about as well as their style — which was all about hairspray, lipstick (everywhere) and spray paint-stencilled clothing — but Manic Street Preachers' debut album remains a lot of fun. Inspired by the gluttony and glam of Guns N' Roses' Appetite for Destruction, Generation Terrorists is full of Slash-inspired solos ("Motorcycle Emptiness"), narcissistic rockers ("You Love Us," "Stay Beautiful") and drugs ("Methadone Pretty"). The fact that it sounds dated is part of its charm — a guest vocal by Traci Lords on "Little Baby Nothing" is deliciously passé. Sure, it didn't go on to sell the 16 million they facetiously predicted, but the Manics fired on all cylinders and delivered everything else they were promising at the time.

Their best-selling album to date, This Is My Truth Tell Me Yours (1998) was the only moment where the Manics decided against changing up their sound. If anything, This Is My Truth delved deeper into the mature sound that Everything Must Go established: the strings were more ostentatious ("The Everlasting"), the rock anthems more anthemic ("You Stole the Sun from My Heart") and the introspective ballads more intimate ("Be a Girl"). And of course, there was the ridiculously named "If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next," which contained a chorus that had no business being infectious, but is anyway.

The most divisive album in the Manics' discography is unquestionably Lifeblood (2004). Both critics and fans — and eventually the band themselves — were lukewarm to the album's polished, soft-edged sound, which bears resemblance to that of both U2 and Coldplay. But seeing as it came after the confusing mess of Know Your Enemy, you can hardly blame them for trying something so easy on the ear. Lifeblood, though, is a fine example of how the Manics can tip the spectrum when they want: this is as opposite to The Holy Bible as it can get. Complaints of being too AOR-friendly were loud and clear, but Lifeblood is deeply misunderstood. The album found the band experimenting with an extravagance they'd never put to tape before, which might have something to do with co-producer Tony Visconti (who, strangely enough, did not produce the Bowie-esque "Always/Never").

Finally there's the mostly acoustic Rewind the Film (2013), and though it often gets overshadowed by its more ambitious companion, Futurology, it's really the yin to that album's yang. Where Futurology was all about pushing their ambition to the max, Rewind the Film was a simpler album that reflect on life as a 40-something. And while it could very well have been a midlife crisis record, Rewind is too lovely and hopeful to deserve that categorization. It's a gorgeously arranged collection of modern pop music that proves the Manics will age gracefully — whenever they're ready to.