Annie Clark has become a modern guitar hero precisely for the fact that half the time, you'd hardly know she was playing guitar. From the blast of purple distortion that detonates in the middle of "Northern Lights" to the pixelated serpent that twists and slithers across the back half of "Rattlesnake," her guitar playing is unfamiliar and difficult, a subversion of the self-indulgent axe-mastery of yore. In its physical shape on stage — gripped tightly and pulled close to the body — the guitar is familiar, a bone thrown to the cantankerous rockists that suggests maybe guitar music isn't really dead and gone. But in its incorporeal presence, squealing and glitching and precise, it becomes unfamiliar again — the sound from the uncanny valley, ricocheting up the mountainside.

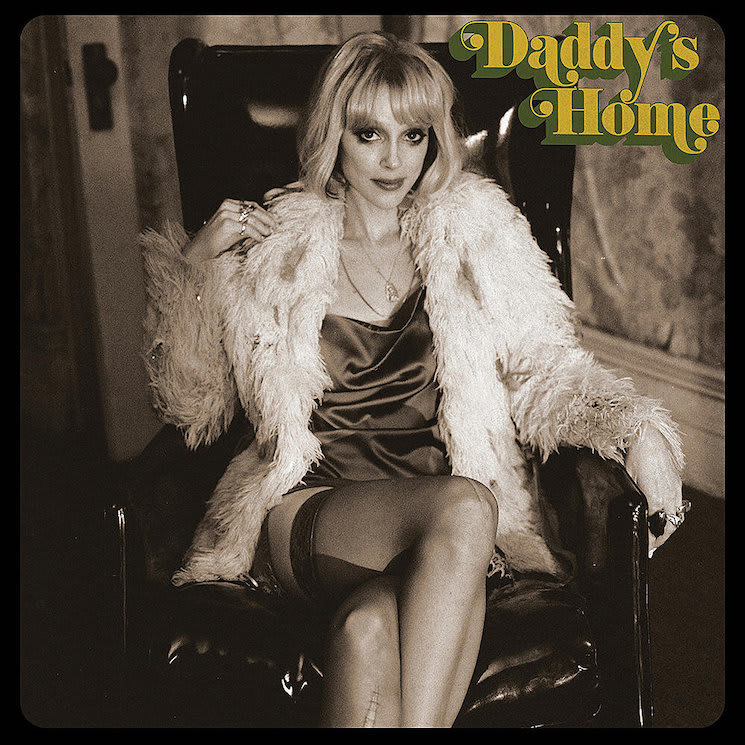

That dichotomy has come to embody the character of St. Vincent on a larger scale too, a shapeshifting rock star who lives in the echo between familiarity and strangeness, sincerity and coldness, expression and calculation. So what happens when the tension is released and the guitar simply becomes a guitar? When the character is no longer severe but severely chill, when the stricture becomes softness? You get Daddy's Home, a great record and a bit of a lesson in the pitfalls of control.

Clark seems to approach each promotional cycle with a loose script of sorts, a protective barrier that ensures there will always be an answer, regardless of the question. For 2014's self-titled album, the language was near-future cult leaders and paramount grooves. For 2017's MASSEDUCTION, it was subjugation and power and slide guitar. It's a pretty understandable antidote to the emotional fatigue of back-to-back-to-back interviews, and a way to keep the conversation manageable and on one's own terms. The trouble comes when the script fails to account for the questions being raised, when the narrative becomes too unwieldy even for its creator.

Daddy's Home is a record about many things — the Sheena Easton-interpolating "My Baby Wants a Baby" breathes new life into a sweet, anticipatory love song by swapping the perspective and twisting all the yearning into a frightened spiral on selfishness, commitment and the weight of legacy. The fingerpicked swirl of "Somebody Like Me" is a treatise on the terrifying rush of love, the risk inherent in giving yourself over to someone and the responsibility in being given over to. "Down" is pure rage, snarling with a funkified version of the incandescent cruelty that powered 2012's "Krokodil" single. It's a rich and complex collection of songs, though you'd hardly know it given the online chatter that surrounds it.

As has been reported ad infinitum since the album's announcement, Clark's father was sentenced to 12 years in 2010 for his role in a $43 million stock-manipulation scheme. Clark has covered this before — recorded in the immediate aftermath of her father's imprisonment, 2011's Strange Mercy was a pained, constricted record that dealt with themes of bondage, isolation and America in the abstract. Daddy's Home was made on the other side, a more humorous and literal affair that attempts to reclaim Clark's story after it was unearthed by tabloids in the wake of her burgeoning celebrity. It's a frequently beautiful record, stretching and dirtying some of the baroque softness that coloured Marry Me and Actor.

But in choosing such an aesthetics-driven version of her father's story as the leading promotional frame, Clark may have done her own work a disservice. Issues of abolition, state violence, mass incarceration, privilege and transparency — it's possible that Clark didn't expect the record to garner such (understandable and unavoidable) real-world baggage. But to suggest that Clark not write about her father's story is, of course, absurd, and to suggest she write it in more palatable or universal terms is equally so. What do we want from our artists if not an unshakeable belief in their own vision? And do we really need a promo cycle that has Clark, of all people, speaking at length on mass incarceration in America? It's hard to know what we want, or how Clark expected this story to be received. But it's a testament to the inherent risk in such strict narrative management, as the realities and complications of many will inevitably impose on the story of one.

The good and simple news is that Daddy's Home shines through the muck that's accumulated around it. Whatever your opinion of the album's campy visual construct or storytelling perspective, there's little denying that sonically, Clark makes the most of her dive into sweaty '70s shimmer. Songs like "Somebody Like Me" and "Down and Out Downtown" soar with a lightness that her music hasn't really touched since Actor's "Just the Same but Brand New," while "…At the Holiday Party" is one of the most straightforward and beautiful things she's ever written. Six-and-a-half minute epic "Live in the Dream" features the first ever honest-to-god St. Vincent shred-fest, a careening and cocky solo that, this far into her tenure as modern guitar master, feels genuinely earned. And though he's only mentioned once in passing, on "Down and Out Downtown," the entire record feels like a cumulative ode to the mercurial Johnny of "Prince Johnny" and "Happy Birthday, Johnny," an album dedicated to troubled friends and wandering spirits.

The halting funk of the title track is a somewhat uncomfortable fit, though Clark's sideways guitar work rescues it. And while it's a thrill musically, the blunt lyrics in "Down" feel at odds with the rest of the record's self-aware mythmaking. Jack Antonoff's production fingers are less obvious here than they were on the bombastic MASSEDUCTION, as both artists flex some new muscles by way of coppery Wurlitzer, sitar-mimicking guitar and melodies that tend toward resolution over whiplash.

Still, it's hard to ignore that, besides "…At the Holiday Party," the Antonoff co-writes are some of the record's least successful moments. Whether it's always relatable or not, Clark does her best work at arm's length, her outward emotional remove part of her imperious appeal. Antonoff's bald-faced sincerity throws things off their axis — St. Vincent records have always been immensely personal and emotional, but the strange magic is in the way she forces you to bring yourself to the music rather than give herself away.

But while Daddy's Home may not be her best record, it's a bold and rewarding one. And if what we expect from our artists is art — uncompromising, singular, sometimes clumsy and rife with feelings or stories both understandable and not — then few comprehend the exchange quite like St. Vincent.

(Concord)That dichotomy has come to embody the character of St. Vincent on a larger scale too, a shapeshifting rock star who lives in the echo between familiarity and strangeness, sincerity and coldness, expression and calculation. So what happens when the tension is released and the guitar simply becomes a guitar? When the character is no longer severe but severely chill, when the stricture becomes softness? You get Daddy's Home, a great record and a bit of a lesson in the pitfalls of control.

Clark seems to approach each promotional cycle with a loose script of sorts, a protective barrier that ensures there will always be an answer, regardless of the question. For 2014's self-titled album, the language was near-future cult leaders and paramount grooves. For 2017's MASSEDUCTION, it was subjugation and power and slide guitar. It's a pretty understandable antidote to the emotional fatigue of back-to-back-to-back interviews, and a way to keep the conversation manageable and on one's own terms. The trouble comes when the script fails to account for the questions being raised, when the narrative becomes too unwieldy even for its creator.

Daddy's Home is a record about many things — the Sheena Easton-interpolating "My Baby Wants a Baby" breathes new life into a sweet, anticipatory love song by swapping the perspective and twisting all the yearning into a frightened spiral on selfishness, commitment and the weight of legacy. The fingerpicked swirl of "Somebody Like Me" is a treatise on the terrifying rush of love, the risk inherent in giving yourself over to someone and the responsibility in being given over to. "Down" is pure rage, snarling with a funkified version of the incandescent cruelty that powered 2012's "Krokodil" single. It's a rich and complex collection of songs, though you'd hardly know it given the online chatter that surrounds it.

As has been reported ad infinitum since the album's announcement, Clark's father was sentenced to 12 years in 2010 for his role in a $43 million stock-manipulation scheme. Clark has covered this before — recorded in the immediate aftermath of her father's imprisonment, 2011's Strange Mercy was a pained, constricted record that dealt with themes of bondage, isolation and America in the abstract. Daddy's Home was made on the other side, a more humorous and literal affair that attempts to reclaim Clark's story after it was unearthed by tabloids in the wake of her burgeoning celebrity. It's a frequently beautiful record, stretching and dirtying some of the baroque softness that coloured Marry Me and Actor.

But in choosing such an aesthetics-driven version of her father's story as the leading promotional frame, Clark may have done her own work a disservice. Issues of abolition, state violence, mass incarceration, privilege and transparency — it's possible that Clark didn't expect the record to garner such (understandable and unavoidable) real-world baggage. But to suggest that Clark not write about her father's story is, of course, absurd, and to suggest she write it in more palatable or universal terms is equally so. What do we want from our artists if not an unshakeable belief in their own vision? And do we really need a promo cycle that has Clark, of all people, speaking at length on mass incarceration in America? It's hard to know what we want, or how Clark expected this story to be received. But it's a testament to the inherent risk in such strict narrative management, as the realities and complications of many will inevitably impose on the story of one.

The good and simple news is that Daddy's Home shines through the muck that's accumulated around it. Whatever your opinion of the album's campy visual construct or storytelling perspective, there's little denying that sonically, Clark makes the most of her dive into sweaty '70s shimmer. Songs like "Somebody Like Me" and "Down and Out Downtown" soar with a lightness that her music hasn't really touched since Actor's "Just the Same but Brand New," while "…At the Holiday Party" is one of the most straightforward and beautiful things she's ever written. Six-and-a-half minute epic "Live in the Dream" features the first ever honest-to-god St. Vincent shred-fest, a careening and cocky solo that, this far into her tenure as modern guitar master, feels genuinely earned. And though he's only mentioned once in passing, on "Down and Out Downtown," the entire record feels like a cumulative ode to the mercurial Johnny of "Prince Johnny" and "Happy Birthday, Johnny," an album dedicated to troubled friends and wandering spirits.

The halting funk of the title track is a somewhat uncomfortable fit, though Clark's sideways guitar work rescues it. And while it's a thrill musically, the blunt lyrics in "Down" feel at odds with the rest of the record's self-aware mythmaking. Jack Antonoff's production fingers are less obvious here than they were on the bombastic MASSEDUCTION, as both artists flex some new muscles by way of coppery Wurlitzer, sitar-mimicking guitar and melodies that tend toward resolution over whiplash.

Still, it's hard to ignore that, besides "…At the Holiday Party," the Antonoff co-writes are some of the record's least successful moments. Whether it's always relatable or not, Clark does her best work at arm's length, her outward emotional remove part of her imperious appeal. Antonoff's bald-faced sincerity throws things off their axis — St. Vincent records have always been immensely personal and emotional, but the strange magic is in the way she forces you to bring yourself to the music rather than give herself away.

But while Daddy's Home may not be her best record, it's a bold and rewarding one. And if what we expect from our artists is art — uncompromising, singular, sometimes clumsy and rife with feelings or stories both understandable and not — then few comprehend the exchange quite like St. Vincent.