Though Joni Mitchell now undeniably stands as one of music's most acclaimed songwriters, she once thought of herself simply as "a painter derailed by circumstance." In addition to her own illustrations that adorned the covers of Song to a Seagull, Ladies of the Canyon and The Hissing of Summer Lawns, Mitchell's self-portraits served as the art for 1969's Clouds, 1994's Turbulent Indigo and 1998's Taming the Tiger.

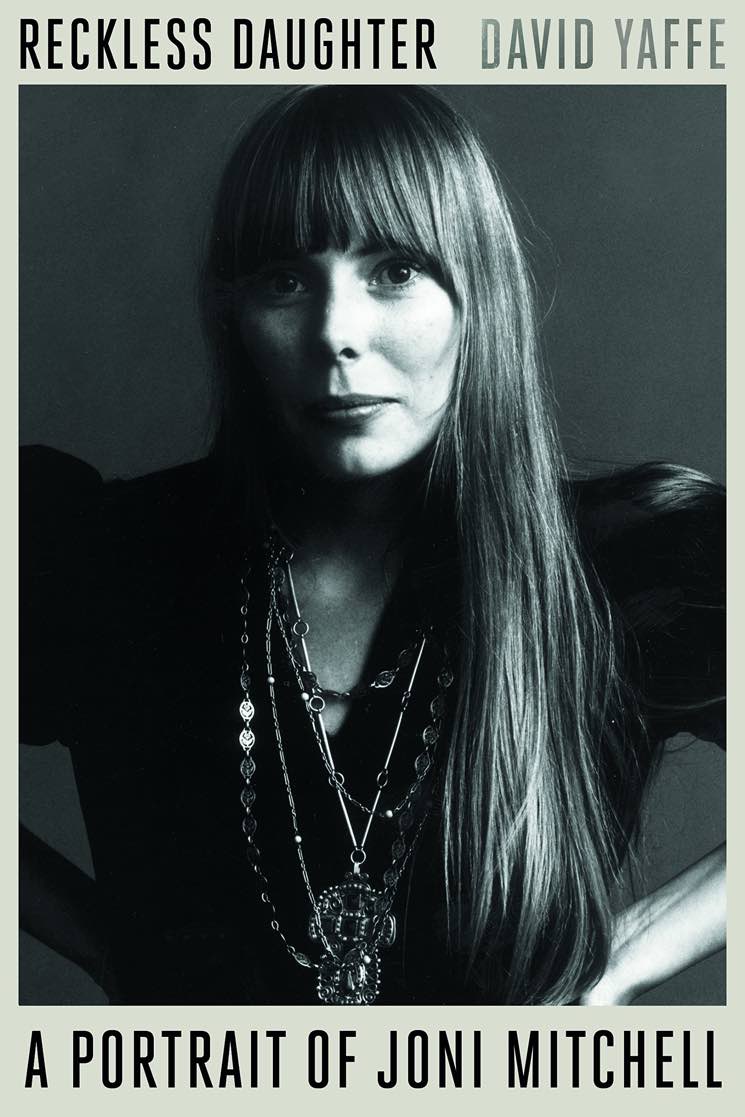

With Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell, author David Yaffe has rendered his own stunning depiction of the artist born Roberta Joan Anderson, sparing little detail in an effort to "understand the mind" behind some of popular music's greatest work. Primarily drawing from a series of interviews he conducted with Mitchell herself, in addition to childhood friends, lovers and musical contemporaries, Yaffe remains unflinching yet fair in charting his subject's unique career arc.

Yaffe begins with Mitchell's childhood in Saskatchewan, where she developed polio at age 10 and was forced to leave her conservative parents to be isolated in a polio colony outside of Saskatoon. Living with the possibility of never walking again, she prayed to "a spirit of destiny or something. I said, 'Give me back my legs and I'll make it up to you.'" It wasn't long before she was walking again.

A short stint in art school led to Mitchell learning to play guitar through a Pete Seeger instructional LP, and in between performing in Calgary's clubs, she became pregnant after sleeping with a classmate. Joni then made the choice to move to Toronto, forming a duo with Chuck Mitchell before marrying him and taking his surname. Their relationship didn't last, with Joni leaving Chuck and putting her newborn daughter up for adoption.

In conversation with Yaffe, Mitchell refers to Chuck as "my first major exploiter." Many of the men that would come to know and work with Mitchell throughout the formative years of her career would become the same. David Crosby found himself in the producer's chair for Mitchell's 1968 debut Song to a Seagull, though his recording techniques resulted in a middling sonic product, leaving Mitchell to credit herself as sole producer on each record until 1985's Dog Eat Dog. After playing the iconic Blue for Kris Kristofferson, he allegedly told Mitchell, "Oh, Joni. Save something for yourself." She was a victim of domestic abuse from her percussionist partner Don Alias, who also once left her alone with idol Miles Davis only to have the jazz legend pass out clutching her ankles after trying to make a move.

Yaffe not only celebrates Mitchell's musical genius, but writes about what makes it so for those not overly familiar with theory: her bout with polio forced experimentation with open tunings, which served better for her fretting hand. A love of jazz music paved the way for her forays into the genre in the late '70s, with her own vocal jazz vocal phrasing improving even as her voice deepened from her smoking habit (which began at nine years old, at one point reached four packs a day). He also gives deserved examinations of the handful of jazz players that helped shape Joni's late-career sound — Jaco Pastorius, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Brian Blade among them.

While many men tried to control her genius, Joni had plenty of admirers, too. Yaffe quotes a journal entry from Jimi Hendrix in which he describes Mitchell as a "fantastic girl with heaven words" while they both played in Ottawa one night in the '60s. He tells of a young Prince Rogers Nelson writing Mitchell fan mail as a boy before befriending her later in life.

Of course, Mitchell is also not without her own contentious points. Her belief of having an "inner black person" led to her dressing up in Blackface for both a Halloween party and the cover of 1977's Don Juan's Reckless Daughter; in both instances, no one realized it was her. And though it feels somewhat glossed over, Mitchell's alleged harassment of her housekeeper (for which she settled out of court) is also mentioned.

Yaffe ends the book with the events after Mitchell's 2015 brain aneurysm, after which she's appeared in public only twice, including once this year (2017). It goes without saying that Mitchell's legacy will live on, but Reckless Daughter does well in taking fans of her work beyond the beloved catalogue staples.

(Harper Collins)With Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell, author David Yaffe has rendered his own stunning depiction of the artist born Roberta Joan Anderson, sparing little detail in an effort to "understand the mind" behind some of popular music's greatest work. Primarily drawing from a series of interviews he conducted with Mitchell herself, in addition to childhood friends, lovers and musical contemporaries, Yaffe remains unflinching yet fair in charting his subject's unique career arc.

Yaffe begins with Mitchell's childhood in Saskatchewan, where she developed polio at age 10 and was forced to leave her conservative parents to be isolated in a polio colony outside of Saskatoon. Living with the possibility of never walking again, she prayed to "a spirit of destiny or something. I said, 'Give me back my legs and I'll make it up to you.'" It wasn't long before she was walking again.

A short stint in art school led to Mitchell learning to play guitar through a Pete Seeger instructional LP, and in between performing in Calgary's clubs, she became pregnant after sleeping with a classmate. Joni then made the choice to move to Toronto, forming a duo with Chuck Mitchell before marrying him and taking his surname. Their relationship didn't last, with Joni leaving Chuck and putting her newborn daughter up for adoption.

In conversation with Yaffe, Mitchell refers to Chuck as "my first major exploiter." Many of the men that would come to know and work with Mitchell throughout the formative years of her career would become the same. David Crosby found himself in the producer's chair for Mitchell's 1968 debut Song to a Seagull, though his recording techniques resulted in a middling sonic product, leaving Mitchell to credit herself as sole producer on each record until 1985's Dog Eat Dog. After playing the iconic Blue for Kris Kristofferson, he allegedly told Mitchell, "Oh, Joni. Save something for yourself." She was a victim of domestic abuse from her percussionist partner Don Alias, who also once left her alone with idol Miles Davis only to have the jazz legend pass out clutching her ankles after trying to make a move.

Yaffe not only celebrates Mitchell's musical genius, but writes about what makes it so for those not overly familiar with theory: her bout with polio forced experimentation with open tunings, which served better for her fretting hand. A love of jazz music paved the way for her forays into the genre in the late '70s, with her own vocal jazz vocal phrasing improving even as her voice deepened from her smoking habit (which began at nine years old, at one point reached four packs a day). He also gives deserved examinations of the handful of jazz players that helped shape Joni's late-career sound — Jaco Pastorius, Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter and Brian Blade among them.

While many men tried to control her genius, Joni had plenty of admirers, too. Yaffe quotes a journal entry from Jimi Hendrix in which he describes Mitchell as a "fantastic girl with heaven words" while they both played in Ottawa one night in the '60s. He tells of a young Prince Rogers Nelson writing Mitchell fan mail as a boy before befriending her later in life.

Of course, Mitchell is also not without her own contentious points. Her belief of having an "inner black person" led to her dressing up in Blackface for both a Halloween party and the cover of 1977's Don Juan's Reckless Daughter; in both instances, no one realized it was her. And though it feels somewhat glossed over, Mitchell's alleged harassment of her housekeeper (for which she settled out of court) is also mentioned.

Yaffe ends the book with the events after Mitchell's 2015 brain aneurysm, after which she's appeared in public only twice, including once this year (2017). It goes without saying that Mitchell's legacy will live on, but Reckless Daughter does well in taking fans of her work beyond the beloved catalogue staples.