When Lana Del Rey burst onto the scene in 2011, critics had a hard time buying her diamond-encrusted sad-girl shtick. Her 2012 major label debut, Born to Die, was derided as a cliché-riddled dreamscape, and as Lana continued with Ultraviolence, Honeymoon and Lust for Life, it was hard to tell whether her patriotic beach-ballads of romance and recklessness were cheeky, honest, or both.

But by 2019, she had found a newly graceful stride chronicling the ecstatic agony of searching for freedom in America's self-indulgent coastal imagination. That year's Norman Fucking Rockwell! topped numerous year-end lists, including our own.

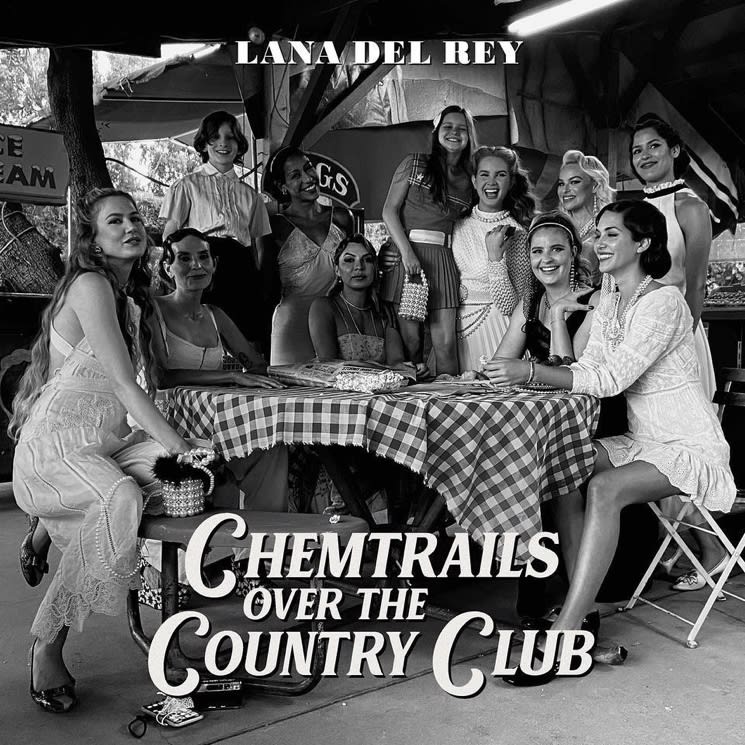

Her sixth studio album, Chemtrails over the Country Club, swaps NFR!'s adored orchestral grandeur for delicate depth. Produced again with Jack Antonoff, it is folksier, centring Lana's poetic voice in a stripped-down version of the world she's spent her career building. Thin layers of trip-hop ambience are woven into acoustic twang and breezy vocals. Lana ponders God, simple romance and wanderlust.

The album's most gorgeous moments are its most timid, its most tragic. In opener "White Dress," Lana's crackling falsetto mourns the distance between her and "simpler days" when feeling eyes on her as she waited tables was enough. "It made me feel like a God," she sings. "It was such a scene / and I felt seen."

Over the course of her first four albums, Lana embraced a hollow fantasy of American exceptionalism coloured by white lines, pretty beaches and broken men. Norman Fucking Rockwell! did the same, but with more wit and truth. The authenticity of Chemtrails makes it once and for all impossible to believe that Lana's longing reflections on the romance of Americana-dreaming are ironic.

In the past, many wondered whether Lana was for real, and to what extent "Lanaland" had been fabricated for consumption. On Chemtrails, it becomes clear that this is the wrong question to ask. Even if the world of Lana is artifice, it is real in these songs. Dripping with nostalgia and a tender desperation, Chemtrails pleads: what if this is all there is? And if it isn't, then what?

Lana's music is a perfect product of the American Dream. And it is a dream that has never felt more dangerous, as America's faulty foundations crumble before our eyes.

Like any product of the American Dream, Lana and her work are riddled with white-washed wilful ignorance: an ignorance as pleasant for the privileged to escape into as it is harmful for everyone else. In the last year, she has been criticized for racist remarks, a tone-deaf statement that Trump's presidency was "necessary," and for posting clips of looters during Black Lives Matter protests. She has been scrutinized for the ways she has spoken about womanhood and abuse, saying that modern feminism lacks space for "fragility" and women like her.

As the public eye has zoomed in, we have been forced to recall that the glittering peak from which Lana sings is not hypothetical. Raised by New York aristocrats, she has been moulded in part by the glamorous upper middle class her art so melodramatically depicts. Although she was praised during Trump's presidency for breaking her tradition of performing in front of an American flag, it is hard to believe that she doesn't still sleep in one, as she sang in "Cola" in 2012.

She touches on the weight of fame and public scrutiny on Chemtrails. On the record's title track, she declares, "I don't care what they think / drag-racing my little red sports car." "Dark But Just A Game," on the other hand, reveals her discontent, as she sings, "I was a pretty little thing / And got a lot to sing, but / Nothing came from either one but pain." The chorus chimes, "No rose left on the vines / Don't even want what's mine / Much less the fame."

Perhaps Lana's world is now, more than ever, symbolic of America itself: a crumbling landscape of empty yearnings and plastic archetypes which distract, if only for a moment, from the violent truths bubbling beneath the surface. Chemtrails over the Country Club is sultry at times, syrupy sweet at others, and sad in a truer way than we have yet seen from Lana. It is a well-woven escape, but it is harder than ever not to wonder: at what cost?

(Polydor)But by 2019, she had found a newly graceful stride chronicling the ecstatic agony of searching for freedom in America's self-indulgent coastal imagination. That year's Norman Fucking Rockwell! topped numerous year-end lists, including our own.

Her sixth studio album, Chemtrails over the Country Club, swaps NFR!'s adored orchestral grandeur for delicate depth. Produced again with Jack Antonoff, it is folksier, centring Lana's poetic voice in a stripped-down version of the world she's spent her career building. Thin layers of trip-hop ambience are woven into acoustic twang and breezy vocals. Lana ponders God, simple romance and wanderlust.

The album's most gorgeous moments are its most timid, its most tragic. In opener "White Dress," Lana's crackling falsetto mourns the distance between her and "simpler days" when feeling eyes on her as she waited tables was enough. "It made me feel like a God," she sings. "It was such a scene / and I felt seen."

Over the course of her first four albums, Lana embraced a hollow fantasy of American exceptionalism coloured by white lines, pretty beaches and broken men. Norman Fucking Rockwell! did the same, but with more wit and truth. The authenticity of Chemtrails makes it once and for all impossible to believe that Lana's longing reflections on the romance of Americana-dreaming are ironic.

In the past, many wondered whether Lana was for real, and to what extent "Lanaland" had been fabricated for consumption. On Chemtrails, it becomes clear that this is the wrong question to ask. Even if the world of Lana is artifice, it is real in these songs. Dripping with nostalgia and a tender desperation, Chemtrails pleads: what if this is all there is? And if it isn't, then what?

Lana's music is a perfect product of the American Dream. And it is a dream that has never felt more dangerous, as America's faulty foundations crumble before our eyes.

Like any product of the American Dream, Lana and her work are riddled with white-washed wilful ignorance: an ignorance as pleasant for the privileged to escape into as it is harmful for everyone else. In the last year, she has been criticized for racist remarks, a tone-deaf statement that Trump's presidency was "necessary," and for posting clips of looters during Black Lives Matter protests. She has been scrutinized for the ways she has spoken about womanhood and abuse, saying that modern feminism lacks space for "fragility" and women like her.

As the public eye has zoomed in, we have been forced to recall that the glittering peak from which Lana sings is not hypothetical. Raised by New York aristocrats, she has been moulded in part by the glamorous upper middle class her art so melodramatically depicts. Although she was praised during Trump's presidency for breaking her tradition of performing in front of an American flag, it is hard to believe that she doesn't still sleep in one, as she sang in "Cola" in 2012.

She touches on the weight of fame and public scrutiny on Chemtrails. On the record's title track, she declares, "I don't care what they think / drag-racing my little red sports car." "Dark But Just A Game," on the other hand, reveals her discontent, as she sings, "I was a pretty little thing / And got a lot to sing, but / Nothing came from either one but pain." The chorus chimes, "No rose left on the vines / Don't even want what's mine / Much less the fame."

Perhaps Lana's world is now, more than ever, symbolic of America itself: a crumbling landscape of empty yearnings and plastic archetypes which distract, if only for a moment, from the violent truths bubbling beneath the surface. Chemtrails over the Country Club is sultry at times, syrupy sweet at others, and sad in a truer way than we have yet seen from Lana. It is a well-woven escape, but it is harder than ever not to wonder: at what cost?