You might have heard of so sad today, a twitter account that revels in laying bare subjects that we're not supposed to discuss in public: depression, desperation, loneliness. Tweets like "sad tonight," "slept with both of your sons" and "sext: nothing matters" would all seem pretty nihilistic if they weren't so crucial to social discourse. So while the account creator recently admitted she's not always necessarily sad, nobody questions the authenticity of the tweets — they fulfill a powerful social role.

Enter Lana Del Rey, who was lambasted upon the breakout release of her album Born to Die in 2012 for the perceived shallowness of her lyrics and her lack of "authenticity" for having changed her name from Lizzy Grant years earlier. Critics seemed oblivious that Del Rey's put-on retro-Americana drama might be important to some listeners (and, you know, part of pop music's rich tradition), and tended to focus on the authenticity of her persona rather than the music itself.

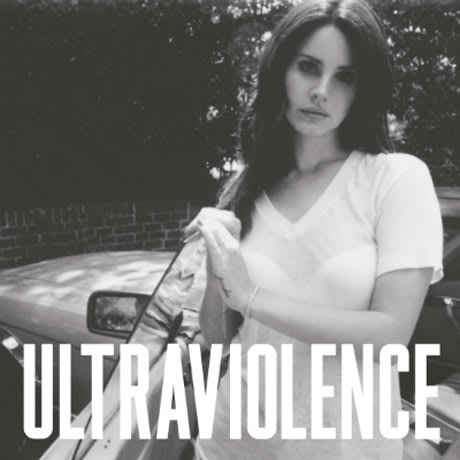

Ultraviolence begins, fearlessly, with hypnotic seven-minute epic "Cruel World," and carries momentum throughout with the St. Vincent-esque waltz of "Shades of Cool" and the nose-thumbing "Fucked My Way Up To The Top." It's all a little more understated than Born to Die, which is a good thing, but it also means that the album tends to run together a little; you can't compare apples and oranges, but on an album full of apples, only the reddest tend to shine.

Those songs, "Pretty When You Cry" and "Money Power Glory," are self-flagellating bits of pop misery that, shallow and self-destructive as they may seem, provide a soundtrack as stylish as it is cathartic. That she cribs liberally — "Old Money" lifts the melody of Nino Rota's Romeo and Juliet classic "A Time For Us" — is incidental to the mood that Del Rey establishes. Ultraviolence prioritizes mood over innovation, classicism over experimentalism, and is better for it.

(Universal)Enter Lana Del Rey, who was lambasted upon the breakout release of her album Born to Die in 2012 for the perceived shallowness of her lyrics and her lack of "authenticity" for having changed her name from Lizzy Grant years earlier. Critics seemed oblivious that Del Rey's put-on retro-Americana drama might be important to some listeners (and, you know, part of pop music's rich tradition), and tended to focus on the authenticity of her persona rather than the music itself.

Ultraviolence begins, fearlessly, with hypnotic seven-minute epic "Cruel World," and carries momentum throughout with the St. Vincent-esque waltz of "Shades of Cool" and the nose-thumbing "Fucked My Way Up To The Top." It's all a little more understated than Born to Die, which is a good thing, but it also means that the album tends to run together a little; you can't compare apples and oranges, but on an album full of apples, only the reddest tend to shine.

Those songs, "Pretty When You Cry" and "Money Power Glory," are self-flagellating bits of pop misery that, shallow and self-destructive as they may seem, provide a soundtrack as stylish as it is cathartic. That she cribs liberally — "Old Money" lifts the melody of Nino Rota's Romeo and Juliet classic "A Time For Us" — is incidental to the mood that Del Rey establishes. Ultraviolence prioritizes mood over innovation, classicism over experimentalism, and is better for it.