The last time I saw Mitski, there wasn’t much to remember. At least, not in comparison to the rest of the day, which included fourth-year classes at the University of Guelph followed by me and my friend Diana taking a bus to Toronto to see Lorde and Run the Jewels with the tickets we’d bought from some guy at the local mall. I had yet to be put onto Mitski, and didn’t take much away from whatever brief chunk of her set we arrived in time to see in the mostly-empty arena. This was 2018, and later that same year, she would release Be the Cowboy and make me live with regret for not paying more attention.

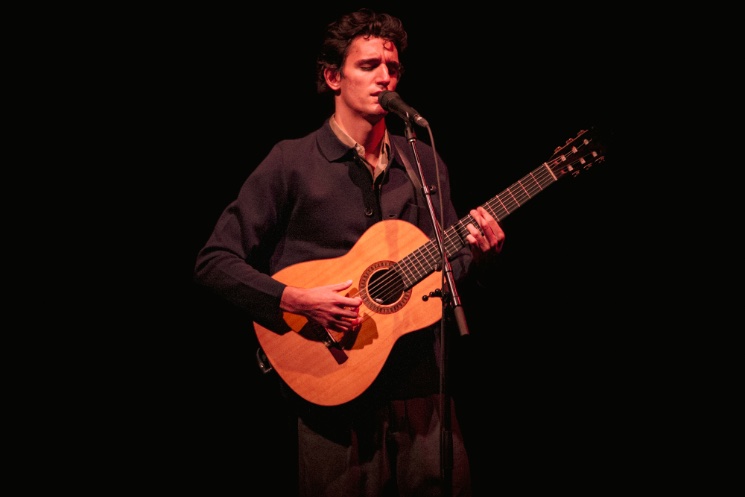

In an effort to rectify the mistakes of 2018, I arrived at Massey Hall in time to catch Mitski’s opener. There’s an ancientness to Tamino’s songs. They’re less about what’s being sung than how it’s being delivered; like how a conduit for holiness appears not to preach any specific gospel, but to affirm that holiness itself exists. It’s about belief — and under a single amber-hued spotlight, he made everyone in the room a believer. As a shepherd might inquire about the source of the heavenly light, the crowd’s stark, pin-drop silence was only interrupted early in the set by a voice asking, “What’s your name?” (Which was swiftly followed by another proclaiming, “You’re so fucking gorgeous!”)

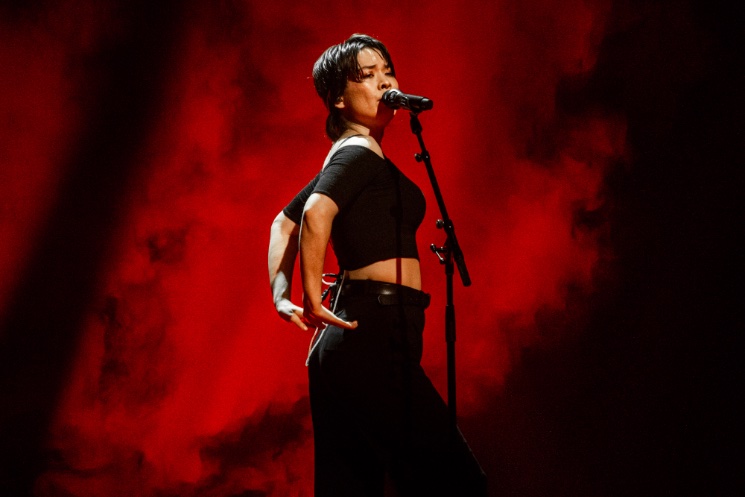

Mirroring my nonchalant jump-scare into caring about her music, Mitski started her show unassumingly. She entered the stage as a background player with the rest of her band, dressed plainly in stagehand black and investigating a giant circular curtain at centre stage when she began to sing “Everyone” from 2022’s Laurel Hell. Before the end of the song, she found herself inside the curtain, casting a looming shadow before dropping the drapes to reveal herself on a raised platform while she sang, “Sometimes I think I am free / Until I find I’m back in line again.”

Mitski’s struggle with being in the public eye has long been part of her lore, adding to her complexity as a performer. There’s a sense that, in some ways, she feels like a puppet on a string. In other moments, she finds herself lost inside the performance, giving her resistance over to the rhythm. This tension is further exacerbated by the fact that, here and now, she’s at the absolute peak of her popularity on the back of her seventh album, The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We. “My Love Mine All Mine” has become a viral hit on TikTok and, everything considered, Mitski is absolutely not the type of singer-songwriter to be excited about this coveted achievement of the present-day music industry.

As such, there’s been much ado about how crowds at her recent shows have been acting, with these newfangled Gen-Z Mitski fans expressing their excitement by yelling things like, “Mother is mothering!” during the performance. I was nervous about this, and those nerves proved unfounded: mercifully, the Toronto audience was respectful, adding fuel to the artist’s monologue about loving this city (and its Asian food) and wanting to move here.

Coupling her distaste for the spotlight with the characteristic intensity of her music, it’s easy to assume that Mitski would be self-serious and kind of shy — which made it all the more charming that she was charismatic, silly and playful when she addressed the audience.

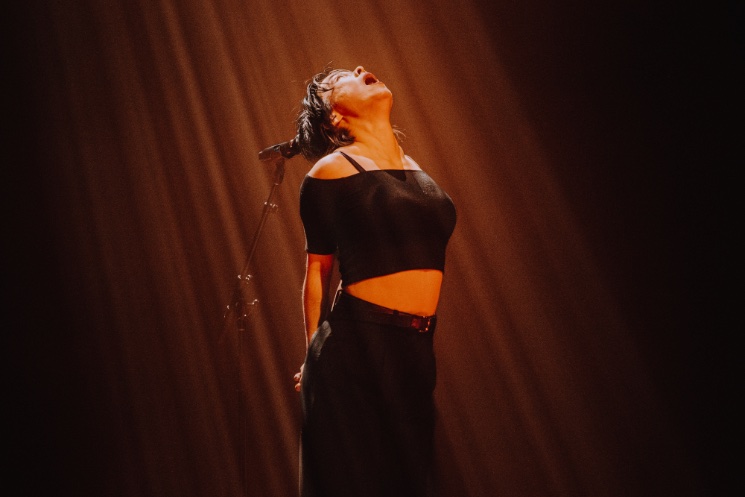

If you’ve seen any photos of her performing, you know that whenever the mic stand comes out at a Mitski show, you’re in for the arm choreography. I was most struck by an early iteration, where she used her free hands to cover her own eyes and then turn outward-facing palms to the crowd, as if to cover ours. There’s discomfort in this seeing and being seen, she says wordlessly. But there’s also a sense of object permanence in her belief — “I have a hope and though she’s blind with no name / She shits where she’s supposed to, feeds herself while I’m away” — as she sang “Buffalo Replaced.”

This expanded into pantomime banjo (it could be any stringed instrument, I suppose, but I’m taking artistic liberties here) on “The Frost,” which is also about being witness-less. A foremost interpretive dancer of our time, Mitski’s performance made me think of a high school girl using a chair for choreography to “Fever” by Peggy Lee, and it’s annoyingly good. And, probably more so than Lady Gaga at the piano in the NYU cafeteria, the girl is too talented (and endearing) for disdain. Mitski stood on said chair during “I Love Me After You” as she sang, “I’m king of all the land,” looking down from her noble vantage point — just to immediately be dethroned by “First Love / Late Spring” from 2014’s Bury Me at Makeout Creek: “One word from you and I would / Jump off of this ledge I’m on, baby.”

Here, the simple set design was amplified by the lighting choices, with Mitski transfixed by a single light beam, which proceeded to multiply like a night sky for “Star.” For obvious reasons, the single beam returned for “Heaven,” then multiplied again — but instead of stars, they became bars entrapping the artist for “I Don’t Like my Mind.”

The peak moment of this triumphantly understated spectacle came during the viral hit “My Love Mine All Mine.” A baby mobile-like structure hung with what appeared to be jagged shards of mirrored glass descended from the ceiling. Then, the jellyfish tentacles slowly re-ascended at her touch during “Last Words of a Shooting Star,” as she sang, “And did you know the liberty bell is a replica / Silently housed in its original walls? And while its dreams played music in the night / Quietly, it was told to believe.”

The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We is a sonic departure for Mitski, especially after the synth-heavy, disco-inspired Laurel Hell. The live arrangements revealed the threads of country music that’ve long been present in her back catalogue, with slight alterations bringing out the twang of beloved staples like “I Bet on Losing Dogs” and “Geyser.” However, Mitski went full honky-tonk bar multiple times, too, rearranging Puberty 2’s “Happy” and “Fireworks,” as well as Be the Cowboy’s “Pink in the Night” and Laurel Hell’s “Love Me More” becoming upbeat, line dancing numbers in the now-Nashvillian’s cabaret.

It was only the encore performances of “Nobody” and “Washing Machine Heart” that the artists toned down the countrification and played the arrangements true to their original recordings. The former is a song so potent that hearing it in a Gap factory outlet could be a religious experience, where those wince-inducing fluorescents could encircle you like the lights shining around Mitski as she stood in the centre of Massey Hall’s stage, perhaps forgetting that we were even watching. Big and small and big and small and big and small again.

That pulsating heart is life-force in Mitski’s songs — where the nebulous force that is love acts as a salve from the inescapable ache of loneliness. After all, this existence is inhospitable. One good movie kiss can save your life, as can brushing your hair naked, laughing in the mirror. It’s this sense of belief that thrusts Mitski into motion as a performer, whether she’s twirling around dreamily, writhing in the fetal position, or crawling like a dog. “You believe me like a god,” she sings on “I’m Your Man,” her voice glassy and clear-eyed, “I’ll betray you like a man.”

Because, as she’s profusely reminded us, she’s only human.