On the eighth trip Gayance took to Brazil, she had a spiritual epiphany. She found herself seeing altars everywhere — in the street, a back alley, a forest — and people would come up to her in prayer. "It was very special," the artist (born Aïsha Vertus) tells Exclaim! over Zoom, "and the work is like the origin story of myself."

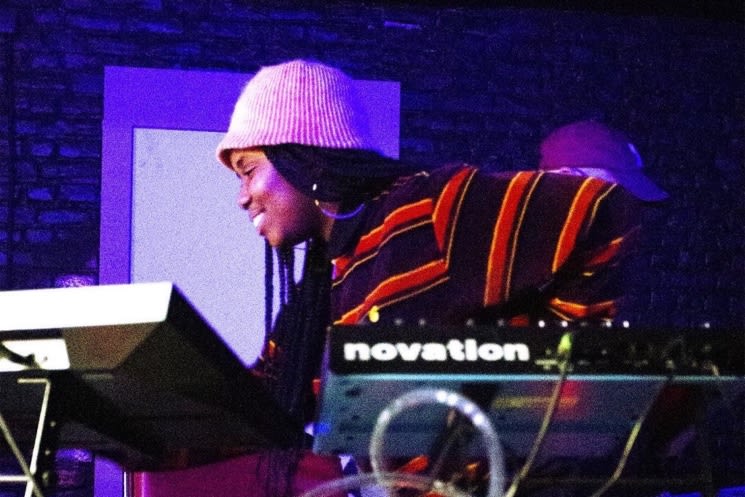

The work in question is the forthcoming debut album from the storied DJ — who got her start in 2013 because she wanted to make her first love a mixtape — as a producer, which she traveled to South America to work on after receiving her first-ever artist's grant.

Ironically, it wasn't until the thick of the pandemic in November 2020 that Gayance began her journey in production: following nearly a decade of recounting and playing a part in elevating the musical landscape of Montreal and its global reputation, she released her first EP, No Toning Down, in 2021.

"I think that was my most depressed. I needed something to hold on [to] — and I could not express my feelings, so I just opened Ableton," she recalls. She called her friend, Moscow-born, Montreal-based DJ and producer Dapapa, who got her set up by putting "the cracked version of Ableton" in her computer.

Another friend, Belgian producer Peter Clinton, explained the basics to her over some Zoom sessions, making use of the feature that allows one participant to control another's cursor. "Then YouTube [tutorials] explained the rest," she shrugs. "I was dedicated and I was like, 'You know what? I'm going to express those feelings.'"

Gayance represents a new wave of pandemic-era producers, many of whom also have taken non-traditional routes into audio and the intersecting worlds of studio and DIY recording.

"The pandemic has definitely forced an already creative industry to get a lot more creative," observes longtime producer Spencer Bleasdale, who has an engineering credit on Elvis Costello and the Imposters' Grammy-winning Look Now and was part of the Bruno Mars recording session for "Uptown Funk" early in his decade working out of Vancouver's heralded Armoury Studios. "But I think the biggest change to come out of all this is that pretty much every session player I know now has at least some sort of home recording setup."

The pandemic also brought him back to his alma mater — Vancouver's Nimbus School of Recording & Media — as a studio recording instructor, teaching students how analog gear works out of the historic old Little Mountain Sound Studios space.

"I think a lot of students come in thinking that professional studio recording is a thing of the past and they don't really need to learn about it, because they have a laptop — but that couldn't be further from the truth," Bleasdale tells Exclaim! "The current reality is that most of the top artists in the world to some extent still work out of professional recording studios."

But he realizes that a lot of his students will do work out of home studios, so he shows them digital parallels to analog techniques. "I'll demonstrate how to set up parallel compression on the SSL [Solid State Logic] console and also without the console in Pro Tools," he says as an example, adding that it's important to note that a home studio can be incredibly similar to a "professional" one if you invest hundreds of thousands of dollars (or more).

"Other than having the comforts of home nearby, I'm not sure if there's anything you can do at a home studio that you couldn't do at a professional studio," Bleasdale admits. However, he's certain of the inverse — like recording a live 40-piece orchestra.

In his own practice as a producer and engineer, he says probably 95 percent of what he records is done at the Armoury — but with mixing, it's more of a 50-50 blend between home and studio.

"The SSL console has a sound you can't replicate at home and I love to use it anytime I can for mixing, but it can be tough for artists to come up with the budget to pay for studio time on top of regular mixing rates," he explains, sometimes doing the majority of a mix at home ahead of having an artist pay for a few hours of studio time to finish it off with analog gear. "It's sort of a best-of-both-worlds approach, and more accessible for indie artists," says Bleasdale.

As an indie artist who has crowdfunded a number of projects over the years, such sacrifices are something Gayance knows too well. "The only thing I can work [on] remotely is a remix," she says, describing her distaste for the COVID-19 era necessity. "I feel like it's very draining to collaborate online because [the sound's] bugging – there's always that technical aspect."

Her ambition as a producer has since taken her from Zoom to various studios around the world, eschewing remote collaborations for in-person meetups whenever possible.

"I'm very boosted by meeting up with people in other settings. Seeing someone working [in the studio], it inspires me — like, that's interesting," Gayance elaborates, "but not as much as real life outside of the studio: talking to people, listening to the music. Especially in Brazil — music is everywhere in the streets," she says, with Brazilian-inspired chord shapes grounding her UK grime-, house- and jungle-infused broken beat music in her own Haitian roots.

Other than knowing 12 scales from going to a music-focused elementary school and learning piano, Gayance has had no real musical training. She's recently thought about pursuing a formal education in audio. "I would like that, but part of me is a school dropout," she laughs, but reiterates that it's eventually going to be her path.

"When I was a student at Nimbus, the main focus was still traditional studio roles and analog gear, mixed with a bit of the digital side of things," Bleasdale recalls of his own time in school — back when the industry was caught in the crossfire of illegal downloading and the explosion of home recording, and there were a lot of questions about the future viability of professional studios. "There's now a relatively clear and established role for home and professional studios in the industry. Both are relevant and will be around for a long time, in ever-evolving forms," he says, with the school's Music Production, Recording and Business program curriculum reflecting the current enmeshment of analog, digital and business worlds.

After all, playing a singular role in the music industry has become a rarity. "A lot of people are their own writers, engineers, producers, managers, social media managers, etc.," Bleasdale explains, emphasizing the importance of understanding all facets — and of showing up, as both he and his mountain of credits will tell you.

"I enjoy working in different positions on different projects, so I definitely encourage versatility in the students," he says, adding that the creative process is always rewarding. "There have been times in the past when I've been the producer on an album for an artist on Monday, and then been the runner, scrubbing floors and making coffee for an artist on Tuesday."

As well as additional gigs in film and curation, Gayance is also a teacher, lending her expertise in DJing and music history to teenagers in high schools and youth centres. They teach her about their reality, while she tells them stories about her friends — among them some of Canada's top electronic music producers like KNLO, Kaytranada, High Klassified and Vince Carter — succeeding while coming from the same neighbourhoods and backgrounds as them.

Gayance admits that her closeness to supernovas in the community made her feel intimidated to start producing herself. "But I was always around that scene to push music," she says of her eclectic, exploratory DJ style.

"I want to live music," she effuses. "I'm not a studio rat. I really want to make music that people can live."

The work in question is the forthcoming debut album from the storied DJ — who got her start in 2013 because she wanted to make her first love a mixtape — as a producer, which she traveled to South America to work on after receiving her first-ever artist's grant.

Ironically, it wasn't until the thick of the pandemic in November 2020 that Gayance began her journey in production: following nearly a decade of recounting and playing a part in elevating the musical landscape of Montreal and its global reputation, she released her first EP, No Toning Down, in 2021.

"I think that was my most depressed. I needed something to hold on [to] — and I could not express my feelings, so I just opened Ableton," she recalls. She called her friend, Moscow-born, Montreal-based DJ and producer Dapapa, who got her set up by putting "the cracked version of Ableton" in her computer.

Another friend, Belgian producer Peter Clinton, explained the basics to her over some Zoom sessions, making use of the feature that allows one participant to control another's cursor. "Then YouTube [tutorials] explained the rest," she shrugs. "I was dedicated and I was like, 'You know what? I'm going to express those feelings.'"

Gayance represents a new wave of pandemic-era producers, many of whom also have taken non-traditional routes into audio and the intersecting worlds of studio and DIY recording.

"The pandemic has definitely forced an already creative industry to get a lot more creative," observes longtime producer Spencer Bleasdale, who has an engineering credit on Elvis Costello and the Imposters' Grammy-winning Look Now and was part of the Bruno Mars recording session for "Uptown Funk" early in his decade working out of Vancouver's heralded Armoury Studios. "But I think the biggest change to come out of all this is that pretty much every session player I know now has at least some sort of home recording setup."

The pandemic also brought him back to his alma mater — Vancouver's Nimbus School of Recording & Media — as a studio recording instructor, teaching students how analog gear works out of the historic old Little Mountain Sound Studios space.

"I think a lot of students come in thinking that professional studio recording is a thing of the past and they don't really need to learn about it, because they have a laptop — but that couldn't be further from the truth," Bleasdale tells Exclaim! "The current reality is that most of the top artists in the world to some extent still work out of professional recording studios."

But he realizes that a lot of his students will do work out of home studios, so he shows them digital parallels to analog techniques. "I'll demonstrate how to set up parallel compression on the SSL [Solid State Logic] console and also without the console in Pro Tools," he says as an example, adding that it's important to note that a home studio can be incredibly similar to a "professional" one if you invest hundreds of thousands of dollars (or more).

"Other than having the comforts of home nearby, I'm not sure if there's anything you can do at a home studio that you couldn't do at a professional studio," Bleasdale admits. However, he's certain of the inverse — like recording a live 40-piece orchestra.

In his own practice as a producer and engineer, he says probably 95 percent of what he records is done at the Armoury — but with mixing, it's more of a 50-50 blend between home and studio.

"The SSL console has a sound you can't replicate at home and I love to use it anytime I can for mixing, but it can be tough for artists to come up with the budget to pay for studio time on top of regular mixing rates," he explains, sometimes doing the majority of a mix at home ahead of having an artist pay for a few hours of studio time to finish it off with analog gear. "It's sort of a best-of-both-worlds approach, and more accessible for indie artists," says Bleasdale.

As an indie artist who has crowdfunded a number of projects over the years, such sacrifices are something Gayance knows too well. "The only thing I can work [on] remotely is a remix," she says, describing her distaste for the COVID-19 era necessity. "I feel like it's very draining to collaborate online because [the sound's] bugging – there's always that technical aspect."

Her ambition as a producer has since taken her from Zoom to various studios around the world, eschewing remote collaborations for in-person meetups whenever possible.

"I'm very boosted by meeting up with people in other settings. Seeing someone working [in the studio], it inspires me — like, that's interesting," Gayance elaborates, "but not as much as real life outside of the studio: talking to people, listening to the music. Especially in Brazil — music is everywhere in the streets," she says, with Brazilian-inspired chord shapes grounding her UK grime-, house- and jungle-infused broken beat music in her own Haitian roots.

Other than knowing 12 scales from going to a music-focused elementary school and learning piano, Gayance has had no real musical training. She's recently thought about pursuing a formal education in audio. "I would like that, but part of me is a school dropout," she laughs, but reiterates that it's eventually going to be her path.

"When I was a student at Nimbus, the main focus was still traditional studio roles and analog gear, mixed with a bit of the digital side of things," Bleasdale recalls of his own time in school — back when the industry was caught in the crossfire of illegal downloading and the explosion of home recording, and there were a lot of questions about the future viability of professional studios. "There's now a relatively clear and established role for home and professional studios in the industry. Both are relevant and will be around for a long time, in ever-evolving forms," he says, with the school's Music Production, Recording and Business program curriculum reflecting the current enmeshment of analog, digital and business worlds.

After all, playing a singular role in the music industry has become a rarity. "A lot of people are their own writers, engineers, producers, managers, social media managers, etc.," Bleasdale explains, emphasizing the importance of understanding all facets — and of showing up, as both he and his mountain of credits will tell you.

"I enjoy working in different positions on different projects, so I definitely encourage versatility in the students," he says, adding that the creative process is always rewarding. "There have been times in the past when I've been the producer on an album for an artist on Monday, and then been the runner, scrubbing floors and making coffee for an artist on Tuesday."

As well as additional gigs in film and curation, Gayance is also a teacher, lending her expertise in DJing and music history to teenagers in high schools and youth centres. They teach her about their reality, while she tells them stories about her friends — among them some of Canada's top electronic music producers like KNLO, Kaytranada, High Klassified and Vince Carter — succeeding while coming from the same neighbourhoods and backgrounds as them.

Gayance admits that her closeness to supernovas in the community made her feel intimidated to start producing herself. "But I was always around that scene to push music," she says of her eclectic, exploratory DJ style.

"I want to live music," she effuses. "I'm not a studio rat. I really want to make music that people can live."