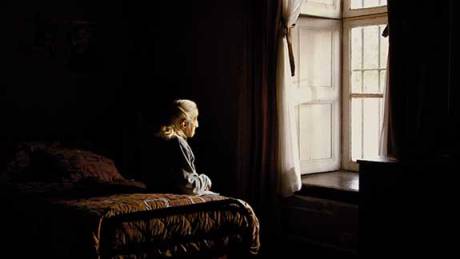

The relevance of comparisons to the works of painter Vilhelm Hammershoi are clear during the opening montage of The Last Station. The residents of Father Hurtado's nursing home in Chile sit silently in dimly lit hallways and bedrooms, staring out windows and looking into an unseen distance with natural light adding shadows and depth of form to their already forlorn and world-weathered faces.

Each image bleeds into the next with the same natural palette exploiting the browns and greys of the starkly decorated facility with the grey skies and leafless trees lining the courtyard. This autumn colour scheme merely reinforces the fall of life, where those living out their last days are shipped off by the living, described by one resident—a radio broadcaster that lists obituaries daily—as trash thrown to the curb, awaiting the death that accompanies us for life.

The rare dialogue uttered throughout this montage of still life imagery reflects the nature of the end: two friends discuss the pain of being left in a home to die alone and a man recites a story about a dimly lit star whose light is unable to reach those around it. These moments, like the carefully considered composition and gradual waiting game of mourning and increasing mortal awareness, are placed deliberately at key moments throughout The Last Station by filmmaking team Cataline Vergara and Cristian Soto, directing the trajectory of futility, patience and the passage of time.

And while the subject matter tends towards the morose, watching a group of elderly people sit around an overcrowded nursing home waiting for their turn to die, the gorgeous imagery and attention to detail surrounding them suggests a lust for life and worldly beauty. The contemplative nature of the photography—in one scene a snail climbs a tree in the foreground while a woman stands motionless and out of focus in the background—reflects the process of life itself.

As the world spins forward, awareness of an ending to it all makes time the enemy; life becomes a reflection of imposed disappointments and concessions. Soto and Vergara frame their film like life itself, doting on the scenery for a while before approaching the evening of it all when death presents and characters collectively grasp onto notions of the afterlife as a means of coping. The brisk, almost incidental, handling of funerals merely adds some context to the frivolity of patiently waiting for that ultimate moment, reiterating that even though death is something we have no control over, doting on its inevitability is like forcing the hand of time and giving up too early.

(Globo Rojo)Each image bleeds into the next with the same natural palette exploiting the browns and greys of the starkly decorated facility with the grey skies and leafless trees lining the courtyard. This autumn colour scheme merely reinforces the fall of life, where those living out their last days are shipped off by the living, described by one resident—a radio broadcaster that lists obituaries daily—as trash thrown to the curb, awaiting the death that accompanies us for life.

The rare dialogue uttered throughout this montage of still life imagery reflects the nature of the end: two friends discuss the pain of being left in a home to die alone and a man recites a story about a dimly lit star whose light is unable to reach those around it. These moments, like the carefully considered composition and gradual waiting game of mourning and increasing mortal awareness, are placed deliberately at key moments throughout The Last Station by filmmaking team Cataline Vergara and Cristian Soto, directing the trajectory of futility, patience and the passage of time.

And while the subject matter tends towards the morose, watching a group of elderly people sit around an overcrowded nursing home waiting for their turn to die, the gorgeous imagery and attention to detail surrounding them suggests a lust for life and worldly beauty. The contemplative nature of the photography—in one scene a snail climbs a tree in the foreground while a woman stands motionless and out of focus in the background—reflects the process of life itself.

As the world spins forward, awareness of an ending to it all makes time the enemy; life becomes a reflection of imposed disappointments and concessions. Soto and Vergara frame their film like life itself, doting on the scenery for a while before approaching the evening of it all when death presents and characters collectively grasp onto notions of the afterlife as a means of coping. The brisk, almost incidental, handling of funerals merely adds some context to the frivolity of patiently waiting for that ultimate moment, reiterating that even though death is something we have no control over, doting on its inevitability is like forcing the hand of time and giving up too early.