The LIVE (Large Interactive Virtual Environment) Lab is undoubtedly one of Canada's most impressive studios, and you've probably never heard of it. As part of McMaster University in Hamilton, ON, the LIVELab is a hyper-tech facility, where science dovetails with sound.

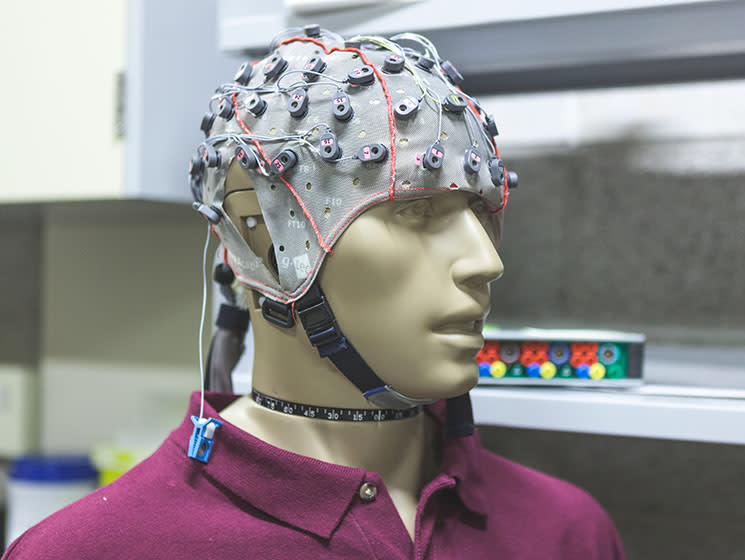

Their goal is to research the many ways in which humans interact with music, consciously and unconsciously. They achieve this by using the spectacular array of equipment at their disposal: the Lab boasts gear that can measure movement, brain responses (EEG), muscle tension and sweating responses, as well as heart-rate and breathing. All of these devices can be hooked up to both audience members and performers to answer questions like: How do musicians read each other while playing? Is movement in the audience contagious? And, ultimately, why do we spend so much time and resources on musical activity?

While the Lab is technically a research facility, it's also a concert venue (catering to 106 people, or about 200 if they take the seats out), which is open to the public. In the past, they've held shows by acts like Orphx, Larnell Lewis, and a release party for Ian Thornley — they even recorded a Terra Lightfoot album there. A recent show featuring pianist Gordon Monahan and dancer Bill Coleman was a prime example of the Lab's most unique quality: its interconnectivity. While Coleman was dancing, he wore an EEG cap, allowing him to control certain aspects of the show, like the amount of reverb from Monahan's piano, and even the lighting, with his mind.

"We also had him do some direct sonification," says Dan Bosnyak, PhD, the Technical Director of LIVELab. "A narrow band of frequencies from his brainwaves were transposed up to the audible range. Normally, brainwaves don't even happen much above 40 hertz, so they aren't really audible, but we pitch-shifted them up to around 200 Hz and added some modulators. So the pianist was essentially playing over the dancer's brainwaves."

At a different performance by local band Illitry, motion detectors were attached to an inflated beach ball, which was then tossed into the crowd. The movement of the ball then determined which of the studio's 75 speakers generated sound, while its height in the air triggered certain filters. In this sense, a LIVELab audience can influence the show in a very real way.

Just standing in the space itself, can be a jaw-dropping experience. Upon first entering the highly-insulated studio, you might assume you're hearing everyone's voice at regular levels, but it's actually a digital interpretation of a "normal" room, fabricated by the active acoustic controls. Once all the systems are turned down, sounds disappear in an instant — a loud clap seems to get swallowed into the ether as soon as it's formed. Conversely, the reverberation can also be turned up to levels that make it sound like a vast cathedral, with a simple flick of the fader. Basically, it can be as small and dead as it is, or as big and echoey as you like.

It's also incredible at recreating specific environments. At one point Bosnyak made it seem like a bee was hovering close by, and because of the number of speakers on hand, the sound of it darting around the room was eerily life-like. He also ran some audio that gave the impression of being in a crowded restaurant, which highlights the treatment aspect of the Lab. Simulating environments like a restaurant can be used to test hearing aids, giving the Lab some real-life, practical use. They also use their muscle tension monitors to look at anxiety in pianists, along with potential treatment, and they're even tackling Parkinson's disease too.

"The link between movement and sound is built into your brain somehow," explains Bosnyak. "Moving to a beat is a lot easier than moving to nothing. When you're ability to initiate movement is damaged by Parkinson's, the beat can get you going when you're unable to. There seems to be a different pathway for creating voluntary movement, so it isn't necessarily a conscious effort. You can obviously decide not to move, but what we've found is that there's some sort of special access between sound and movement, especially in songs with a strong beat."

From their research, the LIVELab have also garnered results, from an experiment with children, about why you might feel a connectedness with your fellow concert-goer.

They've gathered some interesting data on non-verbal cues between performers too. That one in particular was accomplished by experimenting with leadership roles amongst a string quartet. Before each song, the musicians were given a card identifying them as "Leader" or "Not a Leader," in order to research visual communication, but it goes a step beyond even that.

"We had one condition where none of them was the leader, but they didn't know that, they just assumed someone was," says Bosnyak. "And it probably took them ten seconds before they started laughing and stopped playing. They knew pretty much immediately that none of them was the leader. They had the score, but they knew something wasn't right. So, obviously they have some way of communicating non-verbally, which is pretty cool. That's the type of thing we're trying to figure out here — that unspoken coordination music brings out."

If you'd like to read LIVELab's academic paper on body sway, you can do so here.

Their upcoming events can found on their website.

Their goal is to research the many ways in which humans interact with music, consciously and unconsciously. They achieve this by using the spectacular array of equipment at their disposal: the Lab boasts gear that can measure movement, brain responses (EEG), muscle tension and sweating responses, as well as heart-rate and breathing. All of these devices can be hooked up to both audience members and performers to answer questions like: How do musicians read each other while playing? Is movement in the audience contagious? And, ultimately, why do we spend so much time and resources on musical activity?

While the Lab is technically a research facility, it's also a concert venue (catering to 106 people, or about 200 if they take the seats out), which is open to the public. In the past, they've held shows by acts like Orphx, Larnell Lewis, and a release party for Ian Thornley — they even recorded a Terra Lightfoot album there. A recent show featuring pianist Gordon Monahan and dancer Bill Coleman was a prime example of the Lab's most unique quality: its interconnectivity. While Coleman was dancing, he wore an EEG cap, allowing him to control certain aspects of the show, like the amount of reverb from Monahan's piano, and even the lighting, with his mind.

"We also had him do some direct sonification," says Dan Bosnyak, PhD, the Technical Director of LIVELab. "A narrow band of frequencies from his brainwaves were transposed up to the audible range. Normally, brainwaves don't even happen much above 40 hertz, so they aren't really audible, but we pitch-shifted them up to around 200 Hz and added some modulators. So the pianist was essentially playing over the dancer's brainwaves."

At a different performance by local band Illitry, motion detectors were attached to an inflated beach ball, which was then tossed into the crowd. The movement of the ball then determined which of the studio's 75 speakers generated sound, while its height in the air triggered certain filters. In this sense, a LIVELab audience can influence the show in a very real way.

Just standing in the space itself, can be a jaw-dropping experience. Upon first entering the highly-insulated studio, you might assume you're hearing everyone's voice at regular levels, but it's actually a digital interpretation of a "normal" room, fabricated by the active acoustic controls. Once all the systems are turned down, sounds disappear in an instant — a loud clap seems to get swallowed into the ether as soon as it's formed. Conversely, the reverberation can also be turned up to levels that make it sound like a vast cathedral, with a simple flick of the fader. Basically, it can be as small and dead as it is, or as big and echoey as you like.

It's also incredible at recreating specific environments. At one point Bosnyak made it seem like a bee was hovering close by, and because of the number of speakers on hand, the sound of it darting around the room was eerily life-like. He also ran some audio that gave the impression of being in a crowded restaurant, which highlights the treatment aspect of the Lab. Simulating environments like a restaurant can be used to test hearing aids, giving the Lab some real-life, practical use. They also use their muscle tension monitors to look at anxiety in pianists, along with potential treatment, and they're even tackling Parkinson's disease too.

"The link between movement and sound is built into your brain somehow," explains Bosnyak. "Moving to a beat is a lot easier than moving to nothing. When you're ability to initiate movement is damaged by Parkinson's, the beat can get you going when you're unable to. There seems to be a different pathway for creating voluntary movement, so it isn't necessarily a conscious effort. You can obviously decide not to move, but what we've found is that there's some sort of special access between sound and movement, especially in songs with a strong beat."

From their research, the LIVELab have also garnered results, from an experiment with children, about why you might feel a connectedness with your fellow concert-goer.

They've gathered some interesting data on non-verbal cues between performers too. That one in particular was accomplished by experimenting with leadership roles amongst a string quartet. Before each song, the musicians were given a card identifying them as "Leader" or "Not a Leader," in order to research visual communication, but it goes a step beyond even that.

"We had one condition where none of them was the leader, but they didn't know that, they just assumed someone was," says Bosnyak. "And it probably took them ten seconds before they started laughing and stopped playing. They knew pretty much immediately that none of them was the leader. They had the score, but they knew something wasn't right. So, obviously they have some way of communicating non-verbally, which is pretty cool. That's the type of thing we're trying to figure out here — that unspoken coordination music brings out."

If you'd like to read LIVELab's academic paper on body sway, you can do so here.

Their upcoming events can found on their website.