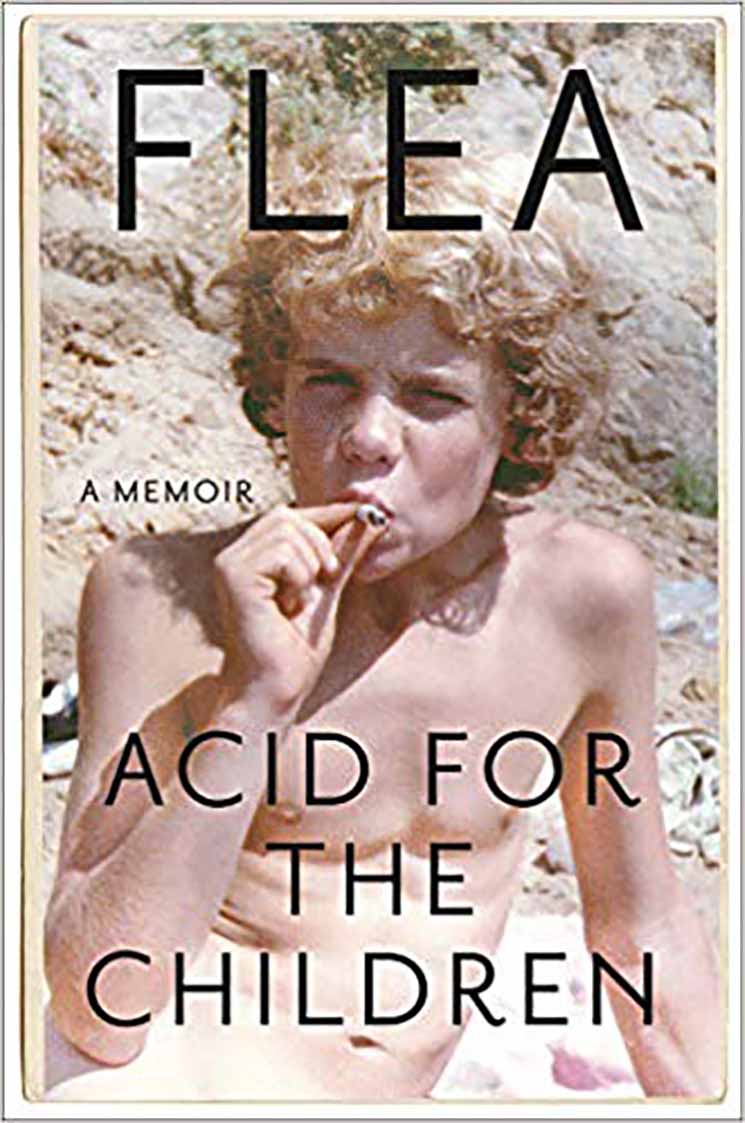

Flea has long been the merry jokester of Red Hot Chilli Peppers — a loveable weirdo known for cartoonish bass slapping, manic onstage energy and frequent nudity. His memoir, Acid for the Children, reveals his dark side.

The book covers his devil-may-care childhood in Australia, his emotionally rocky preadolescence in New York, and his wild teenage years in Los Angeles. His RHCP career is completely omitted — but even though there's no juicy celebrity gossip about the band, there are plenty of fascinating revelations about Flea's early years.

He had a harrowing lack of adult support as a kid, and much of Acid for the Children focus on his emotionally detached mother and harsh, hyper-masculine father. After his parents' divorce, the boy born Michael Balzary then had to contend with a mentally ill, drug-addicted stepfather who was equally prone to tender sweetness and violent meltdowns.

Even when talking about his cruellest moments of lost innocence, Flea writes with a wide-eyed wonderment that splits the difference between hard-earned wisdom and naïveté. He uses hippie-dippy phrases like "deep groove sophistication" and "divine and cosmic rhythm," which might be embarrassingly hokey if they weren't written with such conviction. He seemingly holds nothing back — he describes masturbation in TMI detail, reveals the cruel undercurrent of his friendship with RHCP singer Anthony Kiedis, and gives alarmingly detailed accounts of drug use. Flea never struggled with addiction to the same degree as some of his bandmates, but he still recounts frighteningly dangerous behaviour. During one particularly shocking passage, he describes sharing a dull meth needle with a bunch of people at a party.

The fascinating story is especially vivid thanks to Flea's freewheeling, anything-goes writing style. Some chapters are only a couple of sentences long, and he often foregoes linear narration in favour of a string of roughly chronological anecdotes. At one moment, he'll be describing his group of friends in junior high; the next, he'll devote a three-sentence chapter called "My Little Homies" to The Hobbit. There will be sudden, all-italicized flashes forward to the present day, including one 2016 anecdote that reads like a diary entry. He writes in sentence fragments, full of made-up words and all-caps outbursts — the prosaic equivalent of the playful blasts of frantic funk that have characterized his musical output.

Acid for the Children is bound to be compared to Kiedis's 2004 memoir, Scar Tissue. And while Flea's book is less salacious than his bandmate's, it's stranger, more vulnerable, and every bit as riveting.

(Grand Central Publishing)The book covers his devil-may-care childhood in Australia, his emotionally rocky preadolescence in New York, and his wild teenage years in Los Angeles. His RHCP career is completely omitted — but even though there's no juicy celebrity gossip about the band, there are plenty of fascinating revelations about Flea's early years.

He had a harrowing lack of adult support as a kid, and much of Acid for the Children focus on his emotionally detached mother and harsh, hyper-masculine father. After his parents' divorce, the boy born Michael Balzary then had to contend with a mentally ill, drug-addicted stepfather who was equally prone to tender sweetness and violent meltdowns.

Even when talking about his cruellest moments of lost innocence, Flea writes with a wide-eyed wonderment that splits the difference between hard-earned wisdom and naïveté. He uses hippie-dippy phrases like "deep groove sophistication" and "divine and cosmic rhythm," which might be embarrassingly hokey if they weren't written with such conviction. He seemingly holds nothing back — he describes masturbation in TMI detail, reveals the cruel undercurrent of his friendship with RHCP singer Anthony Kiedis, and gives alarmingly detailed accounts of drug use. Flea never struggled with addiction to the same degree as some of his bandmates, but he still recounts frighteningly dangerous behaviour. During one particularly shocking passage, he describes sharing a dull meth needle with a bunch of people at a party.

The fascinating story is especially vivid thanks to Flea's freewheeling, anything-goes writing style. Some chapters are only a couple of sentences long, and he often foregoes linear narration in favour of a string of roughly chronological anecdotes. At one moment, he'll be describing his group of friends in junior high; the next, he'll devote a three-sentence chapter called "My Little Homies" to The Hobbit. There will be sudden, all-italicized flashes forward to the present day, including one 2016 anecdote that reads like a diary entry. He writes in sentence fragments, full of made-up words and all-caps outbursts — the prosaic equivalent of the playful blasts of frantic funk that have characterized his musical output.

Acid for the Children is bound to be compared to Kiedis's 2004 memoir, Scar Tissue. And while Flea's book is less salacious than his bandmate's, it's stranger, more vulnerable, and every bit as riveting.