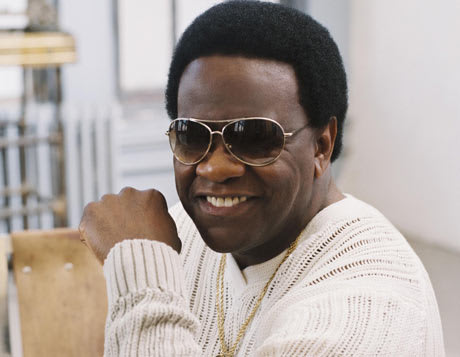

Its almost too easy to describe the story of Al Green as a struggle between the sacred and the profane. Its an American music cliché, but since Green is one of the great American vocalists, he positively owns it. Greens range, his expression, and his natural touch with soul, blues, rock and gospel is inimitable. Yet following a torrid run of success in the early 70s, he bought a church and became the Reverend Al. Religion dominates his life, but unlike so many of his peers, Green has been able to balance the twin pulls of the secular and the spiritual. Though his musical output since the late 70s has only occasionally found a mainstream audience, it remains relatively strong work, and has reached another peak with the release his brilliant new effort, Lay It Down.

1946 to 1960

Al Greene is born in Dansby, Arkansas in 1946, the sixth of ten children to Robert and Cora Greene. Raised in nearby Jacknash, the Greene family are sharecroppers eking out a living. As Green would explain in his 2000 autobiography Take Me to the River, the two churches in town are places of worship and social centres: "To say that church was the hub in which our lives revolved is to state a fact so true for so many black people in America, country born or city bred it was in church that our hopes were elevated, our community consolidated and our spirits regenerated. Years later, Green will speak of his role as Reverend as a means of expressing his personal relationship with Jesus within a community dynamic of worship. His parents move to Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1955, seeking better opportunities for the family. With his fathers guidance, he forms a gospel group called the Greene Brothers at age nine and they achieve moderate success in the Midwest. However, urban life soon introduces Green to the pleasures of rhythm and blues. He sneaks records into the house to avoid the wrath of his father; when the senior Greene discovers his son listening to Jackie Wilson, he throws him out.

1960 to 1967

In 1961, Green joins local R&B band the Creations. They scuffle for a few years, playing a few gigs with Junior Walker and the All Stars as a backup band and then change their name to the Soul Mates. In 1967, two members of the group form a label called Hot Line Music Journal. The groups first single, "Back Up Train hits big, reaching number five in early 1968. "Back up Train shows Greens vocal dexterity even at this early stage, despite the pedestrian musical backing. The Soul Mates play the Apollo and are called back for nine encores of the song. All of their subsequent releases flop and the line-up crumbles.

1968 to 1970

While playing a series of one-nighters in Texas in 1968, Green meets Willie Mitchell. Mitchell is a veteran bandleader in Memphis in the twilight of his performing career; hes also a producer for Hi Records in Memphis. At the time Hi is a minor label putting out competent rockabilly, country and soul sides; hed begun playing a larger role in the labels output and would become its vice-president the following year. Mitchell shapes the labels soul sound with a studio band composed of his stage players teenaged Hodges brothers, Mabon "Teenie, Charles, and Leroy whom he moulds into consummate team players. Their straightforward sound is hard edged and spare, not unlike behind-the-beat country blues with heavier bass. Mitchell describes the encounter with Green to Mojo: "In the summer of 1968 we were booked into Midland, Texas, a huge place that held about 2,500 people. When we pulled up, this cat comes over and says he stranded down there and needs some money to get home to Michigan could he sing a couple of songs? I said maybe, and he started singing a Sam and Dave song. When I heard him sing, I suggested he come back to Memphis with me and cut a record. He said, How long will it take before I become a star? I told him about 18 months. He said, I dont have that long. Green returns to Michigan with a $1,500 loan from Mitchell. Months later, Green shows up on Mitchells doorstep ready to check out what the producer has to offer. Mitchells home base is Royal Recordings in Memphis, a downscale eight-track studio that can only track four tracks at a time; Green will cut all his definitive albums in this humble facility. The first recordings Green does for Hi Records show the pieces of his timeless sound almost already in place. The Hodges brothers, augmented by Booker T and the MGs drummer Al Jackson, make the Deep South sound of the Muscle Shoals (Aretha Franklin) rhythm section seem ornate by comparison. Given the bands economy, Green is free to unleash his young and wild vocals over a dependable groove. Greens first single for Hi (which drops the "e from his last name) is an unlikely cover of "I Want To Hold Your Hand in a manner befitting Otis Reddings take on "Satisfaction, but slower and sexier. His first album, Green Is Blues, released in 1969, is mostly covers, but the odd choice of material makes for interesting listening in retrospect, especially a deeply funky version of the Box Tops "The Letter. Al Green Gets Next To You comes out the following year and shows tremendous improvement in the comfort level between singer, producer and band. Cover versions remain frequent on this release, including an acid blues rework of the Temptations "I Cant Get Next To You, which becomes his first hit. His original material, still in thrall of the great soul shouters, is as hard-driving as he would ever record. The real breakthrough, though, is the plaintive "Tired Of Being Alone, where Green finally dials down his Otis-isms. This song also features the rich accompaniment of backing vocalists Sandra Rhodes, Charles Chalmers and Donna Rhodes, who sound more like Elvis Presleys Jordanaires than a gospel-informed backing trio. The song is both bluesy and smooth, highlighted by Greens silken vocals and it becomes the first of four consecutive gold singles. Following the success of this song, both Hi and Bell Records release collections of Greens Hot Line material.

1971 to 1973

With momentum building, Mitchell and Green release another album within months: Lets Stay Together. The title song needs no introduction to anyone whos attended a North American wedding in the last 35 years, and the album is just as extraordinary. Greens vocal control is magnificent. His originals blend tunefulness with surprising chord changes, and he utterly transforms cover tunes. Case in point is his epic, heartbreaking rendition of the Bee Gees otherwise maudlin "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart in which he literally rises from a whisper to a scream. In a few short years, Mitchell has devised a sound that is tough and symphonic, catchy yet complex. At its heart is hypnotically repetitive kit drumming featuring a damp, boxy snare sound. The sound is built up with punchy horns, melodramatic strings and jazzy guitar obligatos. Every song seems happy and sad all at once. Greens music features neither the massive grandeur of Isaac Hayes, nor a well-oiled studio machine like Marvin Gaye, nor the rumbling funk of Curtis Mayfield. It seems simple and intimate by comparison, though it is highly deliberate and daring in its own way. Green is no longer incendiary like his precursors Jackie Wilson and Otis Redding, but smouldering. Im Still In Love With You is released in mid 1972, less than a year after its predecessor. Its cover, featuring a white-suited, black-socked Al in a white wicker chair is one of the indelible images of the 1970s. The album reaches #4 on the pop charts, and spawns two more hits. One of the most influential tracks is "Love and Happiness, which becomes a sensation in Jamaica, where its guitar intro is worked into many reggae classics of the time. Call Me, from 1973, is another stunning album that marks a change in Greens lyric style. The title track is deeply ambivalent; it beseeches a lover to come back to him, but in a minor key that suggests indecision. "You Ought To Be With Me, another #1 hit, is a shining example of Green and Mitchells style; its typically chugging rhythm section disguises the songs experimentation. Mitchell says, "If you knew all the chords in that song you wouldnt believe it. The chords was so weird, they made it a million seller. Green is a huge concert draw, and his magnetism with women is unquestioned. He enjoys the high life in every sense, with access to women, finery and free flowing party favours. In the summer of 1973 Green is playing shows on the west coast when a life-changing event occurs in Anaheim. While staying in a Disneyland hotel, Green is born again. As he later relates in his autobiography, "About 4:30 that morning, man, I woke up praising and rejoicing. And I had never felt like that before, and I have never felt like that again. So many things were changing so fast, and I had this input, like a charge of electricity. Green continues to play secular music, but begins sermonising on stage. "I was at a club and [I open] up the Bible to Deuteronomy and start reading. I never saw a club clear out so fast in all my life.

1974 to 1979

After the treadmill of recording and performing of the last several years, Green wants to change things up and take a vacation in the Bahamas with the "Hi Rhythm Section, as the Hodges brothers are now known. Mitchell nixes the plans, and all return to work on Living For You, a solid but stand-pat album. Throughout 1974, Green grows closer to Mary Woodson, who, unbeknownst to him, has left her family to be with him. She is a mysterious woman who unsettles Green with a prediction that he will buy a church and become a minister. On October 17, 1974, Woodson sneaks into Greens residence in Memphis and boils a pot of grits. She dumps the hot grits all over Greens naked flesh as he comes out of a shower, and then goes into another room and shoots herself, leaving a note that reads: "the more I trust you, the more you let me down. Green suffers extensive burns and undergoes multiple skin grafts. His rehab lasts eight months, but the emotional scarring is profound. Following these personal upheavals, Greens songwriting grows even more conflicted. He often expresses duelling points of view in his narratives, whether singing about love or, increasingly, the Lord. Al Green Is Love (1975), his first post-grits album, is not the light-hearted affair its title suggests. With the percussion-fuelled "Love Ritual, Greens vocalising suggests speaking in tongues throughout a wickedly funky track. The following year, Green is driving through Memphis when he feels compelled to drive the back roads not far from Graceland. He comes upon a rundown church and decides to buy it, naming it Al Greens Full Gospel Tabernacle Church. A seat in the first pew is dedicated to Woodson. He spends years studying to become a minister, often doing correspondence courses on the road. By 1976, soul music has changed and funk and disco sounds are sweeping aside the deep soul in which Green specialised. Green adapts with the percolating "Full Of Fire, one of his last collaborations with Mitchell. Mitchell sees what is happening with Green on a personal level and is adamant that he will not produce gospel music. Both sense that its time to move on in their respective careers. By the time they split, they have been responsible for 40 million record sales. Green assumes production duties for The Belle Album (1977), something of a concept album exploring his conflict between secular and religious music, summed up in the title tracks couplet: "its you that I want/but its Him that I need. Recorded with a new band at Memphis American Music Studios, which Green had refurbished, the sound is both more downbeat and explicitly funkier as Green proves deft at arranging the new players contributions. Belle is hailed as one of his greatest albums. In 1979, during a stop in Cincinnati on yet another tour, Green falls off the stage and seriously injures himself. He interprets this as a sign from God to stop performing secular music altogether. He receives his ministers license and begins preaching at the Tabernacle full time.

1979 to 1988

Dedicating himself to gospel music, he switches labels from Hi to Myrrh, a small Christian label in Texas. Feeling no pressure to pursue pop production, his records go back to basics, with a small, live band playing straight up soul/funk/gospel grooves with crowd-pleasing slap bass. His voice is undiminished, and the grooves have considerable appeal to middle-aged black audiences, though they dont cross over in the slightest due to their religious content. The 2000 collection Al Greens Greatest Gospel Hits does an excellent job selecting some of his best tracks from the 80s. At the time, rock critics who were still paying attention to Green criticised these low budget efforts, but for latter day funk collectors, each of the albums of this period contains at least a half-dozen serviceable breakbeats. Early 80s albums never sink too low due to the locked-in, live rhythm section, which by and large resist the earthly temptations of cheap digital technology and increasingly pop-oriented R&B production. The complex emotional shades of his classic years are gone, but he can still write a damn good tune with many of the unusual, soulful changes that so characterise his work. His 1981 release, The Lord Will Make A Way, wins him his first Grammy, but the following years Higher Plane is the high water mark of his gospel recordings. Also in 1982, he appears as a minister in the Broadway production Your Arms Too Short To Box With God, which also stars Patti Labelle. In 1984, a film called The Gospel According To Al Green appears, profiling his switch from secular to sacred music. Although Mitchell swore he would never make a gospel record with Green, he relents, and in 1985 He Is The Light comes out on A&M. Mitchell has a few new tricks up his sleeve, including half decent synthesizer work and de rigueur electronic handclaps. Being on a major label, Green leans back towards the mainstream. In 1988, he scores his first top ten hit in more than a decade, a duet on Jackie DeShannons "Put A Little Love In Your Heart with Annie Lennox from the film Scrooged.

1989 to 1995

At this point in his career there is an uneasy balance between his secular and religious sides. His interviews are idiosyncratic, with constant references to himself in third person. Despite the boost to his profile from his recent top ten hit, he mostly sticks to gospel music, though with better distribution than before. In 1993, he records an album for the European market composed mainly of tracks produced by Andy Cox and David Steele (Fine Young Cannibals) and Arthur Baker. The album finds his vocals hemmed in by the unconvincing backing tracks. At a time when Mariah Carey is opening up new avenues for the kind of vocal melisma for which he is renowned, Green hangs back. The album isnt released in America (retitled Your Hearts In Good Hands) for another two years. More mainstream success falls into his lap when he duets with Lyle Lovett in 1994 on a reprise of the cover of Willie Nelsons "Funny How Time Slips Away, which Green originally covered on Call Me. This earns him his ninth Grammy, his first in a non-religious category. He is inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995.

1996 to 2003

While Green had always kept up a steady recording schedule, following his induction into the hall of fame, he puts out only one disc in seven years. He always maintained that after he became born again, the motivation of putting records out for the sake of financial reward was no longer there; this long stretch proves it. During this time, he says in his autobiography he "has his hands full, preaching a sermon on Sunday morning and teaching Bible study on Wednesday night. Nevertheless, he also admits that sometimes, "God will use sexy Al to call His people to Him. He appreciates that people come down to the church hoping hell sing love songs during his three-hour sermons, but obviously refuses to do so. But he still pleases crowds with reworkings of hits like "Full of Fire for Jesus. The anthologising of his career begins in earnest during this time, though Al Greens Greatest Hits (1975) remains the titan among greatest hits albums, and has never stopped selling since its release. These new anthologies bring different aspects of his personality to light. Anthology (1996), though flawed, issues some of his mid-70s preaching from the stage for the first time. The Hi Singles As And Bs (2000) represents what an Arkansas jukebox operator would remember of Greens career, outside of the context of the original albums. Green takes a brief detour into contemporary pop culture with a multi-episode guest spot on Ally McBeal in 1999.

2003 to 2008

In 2003, seemingly out of the blue, Mitchell and Green reunite to work on a secular album, their first collaboration since the 80s. Why then? Green is typically noncommittal, telling CBS News "Its feeling, its emotion. It aint nothing you can talk about. Its just I know when it comes. Billed as a return to the formula that produced so many hits, I Cant Stop is produced at Royal Recordings, featuring the Hodges brothers. Despite all the same ingredients, and septuagenarian Mitchell obviously thrilled to have realised the album for which hed been waiting 30 years, the album doesnt gel. It is critically praised, but its a far cry from the sensitive mixes of his classic albums. Overly resonant drums and nondescript guitar hooks make these strong songs less than the sum of their parts. The album and its successor, 2005s Everythings OK sound like stage band exercises, their MOR productions ignoring the subtle, hip-hop friendly touches that had so marked his classic material. In 2007, according to Billboard, ?uestlove of the Roots boasts to EMI VP Eli Wolf: "You want a real Al Green album? Come see me. He does. ?uestlove states "If it were up to me, I would live all my derivative fantasies out on this record. It would be 1974 all over again, sonically. Three years of effort pay off in Lay It Down, a milestone album for Green. It does indeed sound like 1974 again, though less emotionally fraught. Its tempting to say Green is back on top. However, he may well turn away from his current acclaim and return to the needs of the Tabernacle. The reconciliation between his two sides has been hard won. Hell likely follow his instinct on how to proceed from here; material success will not be a motivating factor for whatever happens next in his life. In a sense his music career has had a happy ending compared to other artists who never found equilibrium between their faith and earthly concerns, like Marvin Gaye. Green has succeeded in reminding the world that his voice is undiminished, and that he can serve the Lord while still thrilling his fans.

1946 to 1960

Al Greene is born in Dansby, Arkansas in 1946, the sixth of ten children to Robert and Cora Greene. Raised in nearby Jacknash, the Greene family are sharecroppers eking out a living. As Green would explain in his 2000 autobiography Take Me to the River, the two churches in town are places of worship and social centres: "To say that church was the hub in which our lives revolved is to state a fact so true for so many black people in America, country born or city bred it was in church that our hopes were elevated, our community consolidated and our spirits regenerated. Years later, Green will speak of his role as Reverend as a means of expressing his personal relationship with Jesus within a community dynamic of worship. His parents move to Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1955, seeking better opportunities for the family. With his fathers guidance, he forms a gospel group called the Greene Brothers at age nine and they achieve moderate success in the Midwest. However, urban life soon introduces Green to the pleasures of rhythm and blues. He sneaks records into the house to avoid the wrath of his father; when the senior Greene discovers his son listening to Jackie Wilson, he throws him out.

1960 to 1967

In 1961, Green joins local R&B band the Creations. They scuffle for a few years, playing a few gigs with Junior Walker and the All Stars as a backup band and then change their name to the Soul Mates. In 1967, two members of the group form a label called Hot Line Music Journal. The groups first single, "Back Up Train hits big, reaching number five in early 1968. "Back up Train shows Greens vocal dexterity even at this early stage, despite the pedestrian musical backing. The Soul Mates play the Apollo and are called back for nine encores of the song. All of their subsequent releases flop and the line-up crumbles.

1968 to 1970

While playing a series of one-nighters in Texas in 1968, Green meets Willie Mitchell. Mitchell is a veteran bandleader in Memphis in the twilight of his performing career; hes also a producer for Hi Records in Memphis. At the time Hi is a minor label putting out competent rockabilly, country and soul sides; hed begun playing a larger role in the labels output and would become its vice-president the following year. Mitchell shapes the labels soul sound with a studio band composed of his stage players teenaged Hodges brothers, Mabon "Teenie, Charles, and Leroy whom he moulds into consummate team players. Their straightforward sound is hard edged and spare, not unlike behind-the-beat country blues with heavier bass. Mitchell describes the encounter with Green to Mojo: "In the summer of 1968 we were booked into Midland, Texas, a huge place that held about 2,500 people. When we pulled up, this cat comes over and says he stranded down there and needs some money to get home to Michigan could he sing a couple of songs? I said maybe, and he started singing a Sam and Dave song. When I heard him sing, I suggested he come back to Memphis with me and cut a record. He said, How long will it take before I become a star? I told him about 18 months. He said, I dont have that long. Green returns to Michigan with a $1,500 loan from Mitchell. Months later, Green shows up on Mitchells doorstep ready to check out what the producer has to offer. Mitchells home base is Royal Recordings in Memphis, a downscale eight-track studio that can only track four tracks at a time; Green will cut all his definitive albums in this humble facility. The first recordings Green does for Hi Records show the pieces of his timeless sound almost already in place. The Hodges brothers, augmented by Booker T and the MGs drummer Al Jackson, make the Deep South sound of the Muscle Shoals (Aretha Franklin) rhythm section seem ornate by comparison. Given the bands economy, Green is free to unleash his young and wild vocals over a dependable groove. Greens first single for Hi (which drops the "e from his last name) is an unlikely cover of "I Want To Hold Your Hand in a manner befitting Otis Reddings take on "Satisfaction, but slower and sexier. His first album, Green Is Blues, released in 1969, is mostly covers, but the odd choice of material makes for interesting listening in retrospect, especially a deeply funky version of the Box Tops "The Letter. Al Green Gets Next To You comes out the following year and shows tremendous improvement in the comfort level between singer, producer and band. Cover versions remain frequent on this release, including an acid blues rework of the Temptations "I Cant Get Next To You, which becomes his first hit. His original material, still in thrall of the great soul shouters, is as hard-driving as he would ever record. The real breakthrough, though, is the plaintive "Tired Of Being Alone, where Green finally dials down his Otis-isms. This song also features the rich accompaniment of backing vocalists Sandra Rhodes, Charles Chalmers and Donna Rhodes, who sound more like Elvis Presleys Jordanaires than a gospel-informed backing trio. The song is both bluesy and smooth, highlighted by Greens silken vocals and it becomes the first of four consecutive gold singles. Following the success of this song, both Hi and Bell Records release collections of Greens Hot Line material.

1971 to 1973

With momentum building, Mitchell and Green release another album within months: Lets Stay Together. The title song needs no introduction to anyone whos attended a North American wedding in the last 35 years, and the album is just as extraordinary. Greens vocal control is magnificent. His originals blend tunefulness with surprising chord changes, and he utterly transforms cover tunes. Case in point is his epic, heartbreaking rendition of the Bee Gees otherwise maudlin "How Can You Mend A Broken Heart in which he literally rises from a whisper to a scream. In a few short years, Mitchell has devised a sound that is tough and symphonic, catchy yet complex. At its heart is hypnotically repetitive kit drumming featuring a damp, boxy snare sound. The sound is built up with punchy horns, melodramatic strings and jazzy guitar obligatos. Every song seems happy and sad all at once. Greens music features neither the massive grandeur of Isaac Hayes, nor a well-oiled studio machine like Marvin Gaye, nor the rumbling funk of Curtis Mayfield. It seems simple and intimate by comparison, though it is highly deliberate and daring in its own way. Green is no longer incendiary like his precursors Jackie Wilson and Otis Redding, but smouldering. Im Still In Love With You is released in mid 1972, less than a year after its predecessor. Its cover, featuring a white-suited, black-socked Al in a white wicker chair is one of the indelible images of the 1970s. The album reaches #4 on the pop charts, and spawns two more hits. One of the most influential tracks is "Love and Happiness, which becomes a sensation in Jamaica, where its guitar intro is worked into many reggae classics of the time. Call Me, from 1973, is another stunning album that marks a change in Greens lyric style. The title track is deeply ambivalent; it beseeches a lover to come back to him, but in a minor key that suggests indecision. "You Ought To Be With Me, another #1 hit, is a shining example of Green and Mitchells style; its typically chugging rhythm section disguises the songs experimentation. Mitchell says, "If you knew all the chords in that song you wouldnt believe it. The chords was so weird, they made it a million seller. Green is a huge concert draw, and his magnetism with women is unquestioned. He enjoys the high life in every sense, with access to women, finery and free flowing party favours. In the summer of 1973 Green is playing shows on the west coast when a life-changing event occurs in Anaheim. While staying in a Disneyland hotel, Green is born again. As he later relates in his autobiography, "About 4:30 that morning, man, I woke up praising and rejoicing. And I had never felt like that before, and I have never felt like that again. So many things were changing so fast, and I had this input, like a charge of electricity. Green continues to play secular music, but begins sermonising on stage. "I was at a club and [I open] up the Bible to Deuteronomy and start reading. I never saw a club clear out so fast in all my life.

1974 to 1979

After the treadmill of recording and performing of the last several years, Green wants to change things up and take a vacation in the Bahamas with the "Hi Rhythm Section, as the Hodges brothers are now known. Mitchell nixes the plans, and all return to work on Living For You, a solid but stand-pat album. Throughout 1974, Green grows closer to Mary Woodson, who, unbeknownst to him, has left her family to be with him. She is a mysterious woman who unsettles Green with a prediction that he will buy a church and become a minister. On October 17, 1974, Woodson sneaks into Greens residence in Memphis and boils a pot of grits. She dumps the hot grits all over Greens naked flesh as he comes out of a shower, and then goes into another room and shoots herself, leaving a note that reads: "the more I trust you, the more you let me down. Green suffers extensive burns and undergoes multiple skin grafts. His rehab lasts eight months, but the emotional scarring is profound. Following these personal upheavals, Greens songwriting grows even more conflicted. He often expresses duelling points of view in his narratives, whether singing about love or, increasingly, the Lord. Al Green Is Love (1975), his first post-grits album, is not the light-hearted affair its title suggests. With the percussion-fuelled "Love Ritual, Greens vocalising suggests speaking in tongues throughout a wickedly funky track. The following year, Green is driving through Memphis when he feels compelled to drive the back roads not far from Graceland. He comes upon a rundown church and decides to buy it, naming it Al Greens Full Gospel Tabernacle Church. A seat in the first pew is dedicated to Woodson. He spends years studying to become a minister, often doing correspondence courses on the road. By 1976, soul music has changed and funk and disco sounds are sweeping aside the deep soul in which Green specialised. Green adapts with the percolating "Full Of Fire, one of his last collaborations with Mitchell. Mitchell sees what is happening with Green on a personal level and is adamant that he will not produce gospel music. Both sense that its time to move on in their respective careers. By the time they split, they have been responsible for 40 million record sales. Green assumes production duties for The Belle Album (1977), something of a concept album exploring his conflict between secular and religious music, summed up in the title tracks couplet: "its you that I want/but its Him that I need. Recorded with a new band at Memphis American Music Studios, which Green had refurbished, the sound is both more downbeat and explicitly funkier as Green proves deft at arranging the new players contributions. Belle is hailed as one of his greatest albums. In 1979, during a stop in Cincinnati on yet another tour, Green falls off the stage and seriously injures himself. He interprets this as a sign from God to stop performing secular music altogether. He receives his ministers license and begins preaching at the Tabernacle full time.

1979 to 1988

Dedicating himself to gospel music, he switches labels from Hi to Myrrh, a small Christian label in Texas. Feeling no pressure to pursue pop production, his records go back to basics, with a small, live band playing straight up soul/funk/gospel grooves with crowd-pleasing slap bass. His voice is undiminished, and the grooves have considerable appeal to middle-aged black audiences, though they dont cross over in the slightest due to their religious content. The 2000 collection Al Greens Greatest Gospel Hits does an excellent job selecting some of his best tracks from the 80s. At the time, rock critics who were still paying attention to Green criticised these low budget efforts, but for latter day funk collectors, each of the albums of this period contains at least a half-dozen serviceable breakbeats. Early 80s albums never sink too low due to the locked-in, live rhythm section, which by and large resist the earthly temptations of cheap digital technology and increasingly pop-oriented R&B production. The complex emotional shades of his classic years are gone, but he can still write a damn good tune with many of the unusual, soulful changes that so characterise his work. His 1981 release, The Lord Will Make A Way, wins him his first Grammy, but the following years Higher Plane is the high water mark of his gospel recordings. Also in 1982, he appears as a minister in the Broadway production Your Arms Too Short To Box With God, which also stars Patti Labelle. In 1984, a film called The Gospel According To Al Green appears, profiling his switch from secular to sacred music. Although Mitchell swore he would never make a gospel record with Green, he relents, and in 1985 He Is The Light comes out on A&M. Mitchell has a few new tricks up his sleeve, including half decent synthesizer work and de rigueur electronic handclaps. Being on a major label, Green leans back towards the mainstream. In 1988, he scores his first top ten hit in more than a decade, a duet on Jackie DeShannons "Put A Little Love In Your Heart with Annie Lennox from the film Scrooged.

1989 to 1995

At this point in his career there is an uneasy balance between his secular and religious sides. His interviews are idiosyncratic, with constant references to himself in third person. Despite the boost to his profile from his recent top ten hit, he mostly sticks to gospel music, though with better distribution than before. In 1993, he records an album for the European market composed mainly of tracks produced by Andy Cox and David Steele (Fine Young Cannibals) and Arthur Baker. The album finds his vocals hemmed in by the unconvincing backing tracks. At a time when Mariah Carey is opening up new avenues for the kind of vocal melisma for which he is renowned, Green hangs back. The album isnt released in America (retitled Your Hearts In Good Hands) for another two years. More mainstream success falls into his lap when he duets with Lyle Lovett in 1994 on a reprise of the cover of Willie Nelsons "Funny How Time Slips Away, which Green originally covered on Call Me. This earns him his ninth Grammy, his first in a non-religious category. He is inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995.

1996 to 2003

While Green had always kept up a steady recording schedule, following his induction into the hall of fame, he puts out only one disc in seven years. He always maintained that after he became born again, the motivation of putting records out for the sake of financial reward was no longer there; this long stretch proves it. During this time, he says in his autobiography he "has his hands full, preaching a sermon on Sunday morning and teaching Bible study on Wednesday night. Nevertheless, he also admits that sometimes, "God will use sexy Al to call His people to Him. He appreciates that people come down to the church hoping hell sing love songs during his three-hour sermons, but obviously refuses to do so. But he still pleases crowds with reworkings of hits like "Full of Fire for Jesus. The anthologising of his career begins in earnest during this time, though Al Greens Greatest Hits (1975) remains the titan among greatest hits albums, and has never stopped selling since its release. These new anthologies bring different aspects of his personality to light. Anthology (1996), though flawed, issues some of his mid-70s preaching from the stage for the first time. The Hi Singles As And Bs (2000) represents what an Arkansas jukebox operator would remember of Greens career, outside of the context of the original albums. Green takes a brief detour into contemporary pop culture with a multi-episode guest spot on Ally McBeal in 1999.

2003 to 2008

In 2003, seemingly out of the blue, Mitchell and Green reunite to work on a secular album, their first collaboration since the 80s. Why then? Green is typically noncommittal, telling CBS News "Its feeling, its emotion. It aint nothing you can talk about. Its just I know when it comes. Billed as a return to the formula that produced so many hits, I Cant Stop is produced at Royal Recordings, featuring the Hodges brothers. Despite all the same ingredients, and septuagenarian Mitchell obviously thrilled to have realised the album for which hed been waiting 30 years, the album doesnt gel. It is critically praised, but its a far cry from the sensitive mixes of his classic albums. Overly resonant drums and nondescript guitar hooks make these strong songs less than the sum of their parts. The album and its successor, 2005s Everythings OK sound like stage band exercises, their MOR productions ignoring the subtle, hip-hop friendly touches that had so marked his classic material. In 2007, according to Billboard, ?uestlove of the Roots boasts to EMI VP Eli Wolf: "You want a real Al Green album? Come see me. He does. ?uestlove states "If it were up to me, I would live all my derivative fantasies out on this record. It would be 1974 all over again, sonically. Three years of effort pay off in Lay It Down, a milestone album for Green. It does indeed sound like 1974 again, though less emotionally fraught. Its tempting to say Green is back on top. However, he may well turn away from his current acclaim and return to the needs of the Tabernacle. The reconciliation between his two sides has been hard won. Hell likely follow his instinct on how to proceed from here; material success will not be a motivating factor for whatever happens next in his life. In a sense his music career has had a happy ending compared to other artists who never found equilibrium between their faith and earthly concerns, like Marvin Gaye. Green has succeeded in reminding the world that his voice is undiminished, and that he can serve the Lord while still thrilling his fans.