Through Studio Ghibli — the legendary studio founded in 1985 — Hayao Miyazaki has written and directed some of the most revered and beloved animated films of the last 30 years, including My Neighbor Totoro, Porco Rosso, Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away. Known for their inventive narrative techniques, gorgeous and intricate illustrations, and humanist and ecological themes, his works have deservedly found their place among the greatest films ever made.

Although he announced his retirement after the release of The Wind Rises in 2013, Miyazaki has returned 10 years later with The Boy and the Heron, his profound and personal 12th feature film.

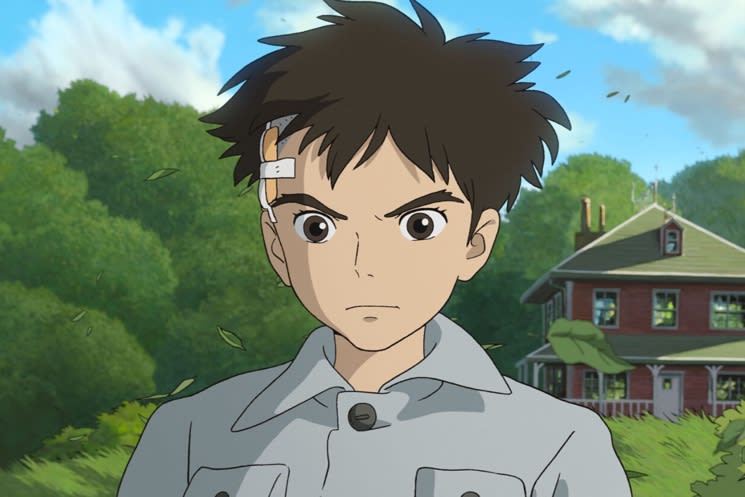

The Boy and the Heron takes place during the Pacific War and follows Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki), a young boy who moves to a small town with his father (Takuya Kimura) after his mother's death. Greeting them in their new home is his father's pregnant new wife, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), who also happens to be his late mother's younger sister. Mahito attempts to deal with his grief, his new surroundings and his new mother, all while being pestered by the large Gray Heron (Masaki Suda). One day, while wandering the expansive grounds, Mahito discovers an abandoned and overgrown tower leading into a fantastical world.

In this world, absolutely nothing is as it seems. In Miyazaki's capable hands, we are presented with a fantastical fever dream of a film reminiscent of a Dantean journey through a bright, lush and cacophonous underworld that takes its iconography from various subjects and genres, including religion, architecture, science fiction, fairy tales and Greek myths. Imaginative and wondrous, the film explores numerous domains and settings, all with unique designs and personalities.

At its core, The Boy and the Heron is a coming-of-age story about death and grief. The film also serves as an autobiography, with various plot points closely resembling Miyazaki's own childhood: Mahito's father being involved in the manufacturing of fighter plane parts, the family's migration from city life into the country, and the loss of a strong mother figure.

As always, Miyazaki is sincere, respecting his characters, the audience and the conceit of the film. Although there's an epic quality to the proceedings, it also revels in the minutia of day-to-day life, with rich yet minimal details, even in the more action-oriented scenes. Joe Hisaishi's gentle, twinkling score accentuates each aspect of the film, big and small, and offers a gorgeous accompaniment that recalls the work of composer Arvo Pärt.

There are moments that are serene, meditative and hushed, but these are always juxtaposed by violence, cacophony and the ever-present Miyazaki Grotesqueries: a gaggle of wrinkled and charmingly misshapen old maids, man-eating parakeets, and the Gray Heron's horrific mouth (you'll get it when you see it). Even the smallest of details thrive within this contrast, such as the Gray Heron's talons clacking on a roof before taking off and Mahito's tears absorbing into the pages of a book.

Similarly, while the film contains fun Miyazaki-isms (including rotund, malleable and ghostly creatures called Warawaras and an insta-classic Miyazaki food scene that is unsurprisingly scrumptious), the innocent naïveté and imagination of childhood in The Boy and the Heron is brutally countered with death, war, the demise of planet Earth, and the need to grow up too quickly.

Once Mahito enters the fantastical realm, Miyazaki's maximalist tendencies are on full display, and, as the film turns overtly political, The Boy and the Heron quickly becomes allegorically overloaded. While the film focuses on the life and death cycle, there's also an ecological element that shows up later on and, with it, a cynicism that has very rarely appeared in Miyazaki's work.

The Boy and the Heron depicts the relationship between humans and nature as particularly precarious — a somewhat harmonious connection that could tip into ruin and abomination at the drop of a block. While Miyazaki isn't eagerly awaiting this fate (he isn't nihilistic after all), he isn't holding out much hope for a positive reconciliation between the two. Miyazaki attempts to say a lot, but his desire to tackle many disparate subjects simultaneously means that not every topic gets its due.

Understandably, comparisons will be made to Miyazaki's earlier works, particularly the fantasy of Spirited Away and the ecological violence of Princess Mononoke. And while there are definite overlaps, The Boy and the Heron feels much more personal, enigmatic and somewhat bitter, all of which tend to come with age.

Although it stretches itself thin with one too many themes and ideas, The Boy and the Heron nevertheless emerges as one of Hayao Miyazaki's most lyrical, cryptic and ambitious works, an uncompromising bildungsroman and a worthy addition to the Studio Ghibli pantheon, even if it doesn't reach the heights of its best works.

Much like life, The Boy and the Heron is beautifully imperfect.

(Cineplex Pictures)Although he announced his retirement after the release of The Wind Rises in 2013, Miyazaki has returned 10 years later with The Boy and the Heron, his profound and personal 12th feature film.

The Boy and the Heron takes place during the Pacific War and follows Mahito Maki (Soma Santoki), a young boy who moves to a small town with his father (Takuya Kimura) after his mother's death. Greeting them in their new home is his father's pregnant new wife, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), who also happens to be his late mother's younger sister. Mahito attempts to deal with his grief, his new surroundings and his new mother, all while being pestered by the large Gray Heron (Masaki Suda). One day, while wandering the expansive grounds, Mahito discovers an abandoned and overgrown tower leading into a fantastical world.

In this world, absolutely nothing is as it seems. In Miyazaki's capable hands, we are presented with a fantastical fever dream of a film reminiscent of a Dantean journey through a bright, lush and cacophonous underworld that takes its iconography from various subjects and genres, including religion, architecture, science fiction, fairy tales and Greek myths. Imaginative and wondrous, the film explores numerous domains and settings, all with unique designs and personalities.

At its core, The Boy and the Heron is a coming-of-age story about death and grief. The film also serves as an autobiography, with various plot points closely resembling Miyazaki's own childhood: Mahito's father being involved in the manufacturing of fighter plane parts, the family's migration from city life into the country, and the loss of a strong mother figure.

As always, Miyazaki is sincere, respecting his characters, the audience and the conceit of the film. Although there's an epic quality to the proceedings, it also revels in the minutia of day-to-day life, with rich yet minimal details, even in the more action-oriented scenes. Joe Hisaishi's gentle, twinkling score accentuates each aspect of the film, big and small, and offers a gorgeous accompaniment that recalls the work of composer Arvo Pärt.

There are moments that are serene, meditative and hushed, but these are always juxtaposed by violence, cacophony and the ever-present Miyazaki Grotesqueries: a gaggle of wrinkled and charmingly misshapen old maids, man-eating parakeets, and the Gray Heron's horrific mouth (you'll get it when you see it). Even the smallest of details thrive within this contrast, such as the Gray Heron's talons clacking on a roof before taking off and Mahito's tears absorbing into the pages of a book.

Similarly, while the film contains fun Miyazaki-isms (including rotund, malleable and ghostly creatures called Warawaras and an insta-classic Miyazaki food scene that is unsurprisingly scrumptious), the innocent naïveté and imagination of childhood in The Boy and the Heron is brutally countered with death, war, the demise of planet Earth, and the need to grow up too quickly.

Once Mahito enters the fantastical realm, Miyazaki's maximalist tendencies are on full display, and, as the film turns overtly political, The Boy and the Heron quickly becomes allegorically overloaded. While the film focuses on the life and death cycle, there's also an ecological element that shows up later on and, with it, a cynicism that has very rarely appeared in Miyazaki's work.

The Boy and the Heron depicts the relationship between humans and nature as particularly precarious — a somewhat harmonious connection that could tip into ruin and abomination at the drop of a block. While Miyazaki isn't eagerly awaiting this fate (he isn't nihilistic after all), he isn't holding out much hope for a positive reconciliation between the two. Miyazaki attempts to say a lot, but his desire to tackle many disparate subjects simultaneously means that not every topic gets its due.

Understandably, comparisons will be made to Miyazaki's earlier works, particularly the fantasy of Spirited Away and the ecological violence of Princess Mononoke. And while there are definite overlaps, The Boy and the Heron feels much more personal, enigmatic and somewhat bitter, all of which tend to come with age.

Although it stretches itself thin with one too many themes and ideas, The Boy and the Heron nevertheless emerges as one of Hayao Miyazaki's most lyrical, cryptic and ambitious works, an uncompromising bildungsroman and a worthy addition to the Studio Ghibli pantheon, even if it doesn't reach the heights of its best works.

Much like life, The Boy and the Heron is beautifully imperfect.