Why did Steven Soderbergh, a director who tends to craft films with allegorical underpinnings or tongue-in-cheek irony, decide to portray the loosely biographical tale of Channing Tatum's stripper past?

Is Magic Mike a parable about the economy (there are a few cursory references to the mismanagement of funds, to the collapse of the financial world, to Rich Dad Poor Dad, a book that differentiates the rich from the middle class by how the former make their money work for them)? Is it a critique on capitalism? Is it a continuation of Soderbergh's interest in the commodification of bodies, sexuality and intimacy? Or is it — can it really be — a straightforward crowd-pleaser about the world of male stripping meant to appeal to a certain type of woman and homosexual man?

Whatever intentions informed the making of Magic Mike, the result is a predictable, clichéd story that fails to either titillate or provoke much reflection. The movie follows the titular character, a self-professed entrepreneur who spends negligible time on said entrepreneurial interests, as he strips, beds women and tries to figure out his future.

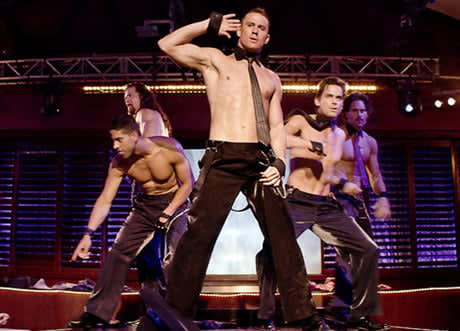

Magic Mike features plenty of strip-club performances involving cheesy choreographed dance routines, impossibly toned bare asses and the dry-humping of various animate and inanimate objects. The actors are enthusiastic and game during these silly sequences, none more so than Channing Tatum, who displays an impressive amount of kinaesthetic intelligence and some self-awareness as he gyrates on the stage.

In fact, Tatum might well be the best thing about this movie, which is surprising. His delivery of lines, particularly when luring women to the strip club or playfully disparaging his protégé, Adam (Alex Pettyfer), is often amusing and natural sounding, and he occasionally exhibits something akin to charisma.

But so what? Tatum's presence isn't enough to carry this movie for anyone interested in something more than a flash of flesh. With a script lacking in originality and insight (including a dreadful drug subplot and a questionable romance addendum), a decidedly tame overall tone, as well as a canned resolution, Magic Mike proves hollow. The few references to the economy are so perfunctory that they can't viably be considered subtext. The movie fails to properly address notions of narcissism and voyeurism, and only superficially handles the expendability of talent in fields that trade on physicality (e.g., stripping and modeling).

As the director, editor and pseudonymous cinematographer of Magic Mike, Soderbergh's involvement in this generic feeling, quasi-genre experiment remains curious. The meagre special features include extended dance scenes and a fleeting behind-the-scenes trip with cast and crew. Supplemental bonus material, such as an in-depth interview with Soderbergh about why he chose to make Magic Mike, or commentary tracks with the director and the cast (it would be great to hear them discuss a mise-en-scène involving a penile enhancement device or why Cody Horn, the daughter of the former President/COO of Warner Brothers, was cast), would prove revealing.

(Warner)Is Magic Mike a parable about the economy (there are a few cursory references to the mismanagement of funds, to the collapse of the financial world, to Rich Dad Poor Dad, a book that differentiates the rich from the middle class by how the former make their money work for them)? Is it a critique on capitalism? Is it a continuation of Soderbergh's interest in the commodification of bodies, sexuality and intimacy? Or is it — can it really be — a straightforward crowd-pleaser about the world of male stripping meant to appeal to a certain type of woman and homosexual man?

Whatever intentions informed the making of Magic Mike, the result is a predictable, clichéd story that fails to either titillate or provoke much reflection. The movie follows the titular character, a self-professed entrepreneur who spends negligible time on said entrepreneurial interests, as he strips, beds women and tries to figure out his future.

Magic Mike features plenty of strip-club performances involving cheesy choreographed dance routines, impossibly toned bare asses and the dry-humping of various animate and inanimate objects. The actors are enthusiastic and game during these silly sequences, none more so than Channing Tatum, who displays an impressive amount of kinaesthetic intelligence and some self-awareness as he gyrates on the stage.

In fact, Tatum might well be the best thing about this movie, which is surprising. His delivery of lines, particularly when luring women to the strip club or playfully disparaging his protégé, Adam (Alex Pettyfer), is often amusing and natural sounding, and he occasionally exhibits something akin to charisma.

But so what? Tatum's presence isn't enough to carry this movie for anyone interested in something more than a flash of flesh. With a script lacking in originality and insight (including a dreadful drug subplot and a questionable romance addendum), a decidedly tame overall tone, as well as a canned resolution, Magic Mike proves hollow. The few references to the economy are so perfunctory that they can't viably be considered subtext. The movie fails to properly address notions of narcissism and voyeurism, and only superficially handles the expendability of talent in fields that trade on physicality (e.g., stripping and modeling).

As the director, editor and pseudonymous cinematographer of Magic Mike, Soderbergh's involvement in this generic feeling, quasi-genre experiment remains curious. The meagre special features include extended dance scenes and a fleeting behind-the-scenes trip with cast and crew. Supplemental bonus material, such as an in-depth interview with Soderbergh about why he chose to make Magic Mike, or commentary tracks with the director and the cast (it would be great to hear them discuss a mise-en-scène involving a penile enhancement device or why Cody Horn, the daughter of the former President/COO of Warner Brothers, was cast), would prove revealing.