Theres something Ill never forget Fred Eaglesmith saying in the middle of one of his shows about how someday southern Ontario will be regarded as highly as Texas for producing the best singer-songwriters in the world. Although he didnt refer to any specifically by name, Eaglesmith was surely thinking of Willie P. Bennett, his longtime band-mate and inconspicuous inspiration to dozens of other artists over his 40-year performing career. Bennett died at his home in Peterborough, Ontario on February 15, while still in the process of recovering from a heart attack that kept him off the road for close to a year.

What Bennett leaves behind is a relatively slim catalogue of five albums under his own name, yet all of them have come to be treasured as contemporary Canadian folk classics. His honest, rough-hewn, and at the same time deeply poetic style always steered clear of popular trends, which resulted in Bennetts reputation mostly being trumpeted by his peers, including Eaglesmith, Bruce Cockburn, and his first producer, David Essig. In fact, Bennett didnt really achieve widespread notoriety until the late 90s when Tom Wilson, Stephen Fearing and Colin Linden formed Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, and released their first album, High Or Hurtin, largely comprised of Bennetts songs. Following this, he made his first solo album in over a decade, Heartstrings, which won a Juno Award in 1999.

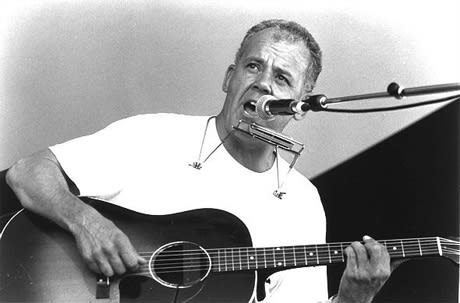

Still, Bennett never courted fame. Instead, he often went through long periods of developing other musical skills aside from his tremendous songwriting gifts, leading to frequent stretches as a sideman. Scott Merritt, who worked peripherally on Heartstrings and produced many of Eaglesmiths records, says Bennetts greatest attribute was "a natural sense of time. The one thing I remember vividly is the way his heel would rock when he played. It rocked the right way, and it was a beautiful thing when you noticed it. You could hear the same thing in his voice. Whatever he sang was immediately believable. It could hit you like an arrow, and thats a really rare thing.

Bennett emerged from the late 60s Toronto folk scene, and first gained attention when his song "White Line was covered by David Wiffen on his acclaimed 1973 Cockburn-produced album Coast To Coast Fever. After a period of playing bluegrass with the Bone China Band, Bennett recorded "White Line himself two years later, including it on his debut album Tryin To Start Out Clean, which he released on his own label, Woodshed Records. This heralded his most prolific period as he made two more albums, 1977s Hobos Taunt and 1978s Blackie and the Rodeo King, in quick succession at Hamiltons Grant Avenue Studios with fledgling engineers Bob and Daniel Lanois.

However, by then Bennett was drawn back into playing bluegrass, where for the next several years he played harmonica with London, Ontarios the Dixie Flyers. In the early 80s he began playing as a duo with Colin Linden who remembers those days as an important part of his musical education. "We were almost inseparable for about six years, and I played his music more than I did my own, Linden says. "Although hed made a conscious decision before then not to fall into that treadmill of continually trying to build yourself up and keep going for bigger gigs, I wouldnt say he wasnt ambitious. In fact, he was very productive as far as songwriting went. I guess what I learned most from that time was that the more you play certain songs you love, the more that the truths contained in those songs begin to resonate within your own life. That kind of stuff never goes away, it just continues to get bigger.

Bennett wound up recording some of that early 80s material on The Lucky Ones, originally put out on cassette before given a proper release on Duke Street Records in 1989. A year later, Prairie Oysters version of the track "Goodbye, So Long, Hello, co-written with that bands front-man Russell de Carle, was named the Canadian Country Music Associations Song of the Year. Once again though, Bennett seemingly refused to build upon this momentum, opting instead to put his energy into mastering the mandolin. By the early 90s, he was a full-time member of Fred Eaglesmiths band, the Flying Squirrels, and often handling road-managing duties as well.

Although Eaglesmiths work could stand on its own, most fans considered the addition of Bennett to the mix a dream combination. Scott Merritt concurs, saying, "On the last few albums, Fred just sent me the tracks and gave me a lot of leeway to do what I wanted with them. Id start listening to them individually, and whenever Id get to Willies parts, it would be like this light coming through the speakers. People often wondered why he remained so loyal to Fred, but I can sympathise with wanting to just experience the joy of playing music without having to attend to all the other aspects of the business. I think he knew he had this natural gift and he wanted to protect it.

Sadly, Bennetts heart attack last year had prompted him to start working on a new solo project and to tour again on his own. Linden says hes confident that a portion of unreleased material will come out in some form eventually. Yet, hes also confident that Bennett would be at peace with his legacy. "I think what he was most happy about when we started Blackie and the Rodeo Kings was that it meant his songs would be out there without him having to go out and play them, Linden says. "But then a song like White Line, which he wrote when he was 16 or 17, I still think may be the greatest song ever written about being stranded, whether its somewhere in Canada in the middle of winter, or anywhere else in the world. Theres something so evocative in it about being trapped by your own need for freedom. That kind of thing will ring true forever.

What Bennett leaves behind is a relatively slim catalogue of five albums under his own name, yet all of them have come to be treasured as contemporary Canadian folk classics. His honest, rough-hewn, and at the same time deeply poetic style always steered clear of popular trends, which resulted in Bennetts reputation mostly being trumpeted by his peers, including Eaglesmith, Bruce Cockburn, and his first producer, David Essig. In fact, Bennett didnt really achieve widespread notoriety until the late 90s when Tom Wilson, Stephen Fearing and Colin Linden formed Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, and released their first album, High Or Hurtin, largely comprised of Bennetts songs. Following this, he made his first solo album in over a decade, Heartstrings, which won a Juno Award in 1999.

Still, Bennett never courted fame. Instead, he often went through long periods of developing other musical skills aside from his tremendous songwriting gifts, leading to frequent stretches as a sideman. Scott Merritt, who worked peripherally on Heartstrings and produced many of Eaglesmiths records, says Bennetts greatest attribute was "a natural sense of time. The one thing I remember vividly is the way his heel would rock when he played. It rocked the right way, and it was a beautiful thing when you noticed it. You could hear the same thing in his voice. Whatever he sang was immediately believable. It could hit you like an arrow, and thats a really rare thing.

Bennett emerged from the late 60s Toronto folk scene, and first gained attention when his song "White Line was covered by David Wiffen on his acclaimed 1973 Cockburn-produced album Coast To Coast Fever. After a period of playing bluegrass with the Bone China Band, Bennett recorded "White Line himself two years later, including it on his debut album Tryin To Start Out Clean, which he released on his own label, Woodshed Records. This heralded his most prolific period as he made two more albums, 1977s Hobos Taunt and 1978s Blackie and the Rodeo King, in quick succession at Hamiltons Grant Avenue Studios with fledgling engineers Bob and Daniel Lanois.

However, by then Bennett was drawn back into playing bluegrass, where for the next several years he played harmonica with London, Ontarios the Dixie Flyers. In the early 80s he began playing as a duo with Colin Linden who remembers those days as an important part of his musical education. "We were almost inseparable for about six years, and I played his music more than I did my own, Linden says. "Although hed made a conscious decision before then not to fall into that treadmill of continually trying to build yourself up and keep going for bigger gigs, I wouldnt say he wasnt ambitious. In fact, he was very productive as far as songwriting went. I guess what I learned most from that time was that the more you play certain songs you love, the more that the truths contained in those songs begin to resonate within your own life. That kind of stuff never goes away, it just continues to get bigger.

Bennett wound up recording some of that early 80s material on The Lucky Ones, originally put out on cassette before given a proper release on Duke Street Records in 1989. A year later, Prairie Oysters version of the track "Goodbye, So Long, Hello, co-written with that bands front-man Russell de Carle, was named the Canadian Country Music Associations Song of the Year. Once again though, Bennett seemingly refused to build upon this momentum, opting instead to put his energy into mastering the mandolin. By the early 90s, he was a full-time member of Fred Eaglesmiths band, the Flying Squirrels, and often handling road-managing duties as well.

Although Eaglesmiths work could stand on its own, most fans considered the addition of Bennett to the mix a dream combination. Scott Merritt concurs, saying, "On the last few albums, Fred just sent me the tracks and gave me a lot of leeway to do what I wanted with them. Id start listening to them individually, and whenever Id get to Willies parts, it would be like this light coming through the speakers. People often wondered why he remained so loyal to Fred, but I can sympathise with wanting to just experience the joy of playing music without having to attend to all the other aspects of the business. I think he knew he had this natural gift and he wanted to protect it.

Sadly, Bennetts heart attack last year had prompted him to start working on a new solo project and to tour again on his own. Linden says hes confident that a portion of unreleased material will come out in some form eventually. Yet, hes also confident that Bennett would be at peace with his legacy. "I think what he was most happy about when we started Blackie and the Rodeo Kings was that it meant his songs would be out there without him having to go out and play them, Linden says. "But then a song like White Line, which he wrote when he was 16 or 17, I still think may be the greatest song ever written about being stranded, whether its somewhere in Canada in the middle of winter, or anywhere else in the world. Theres something so evocative in it about being trapped by your own need for freedom. That kind of thing will ring true forever.