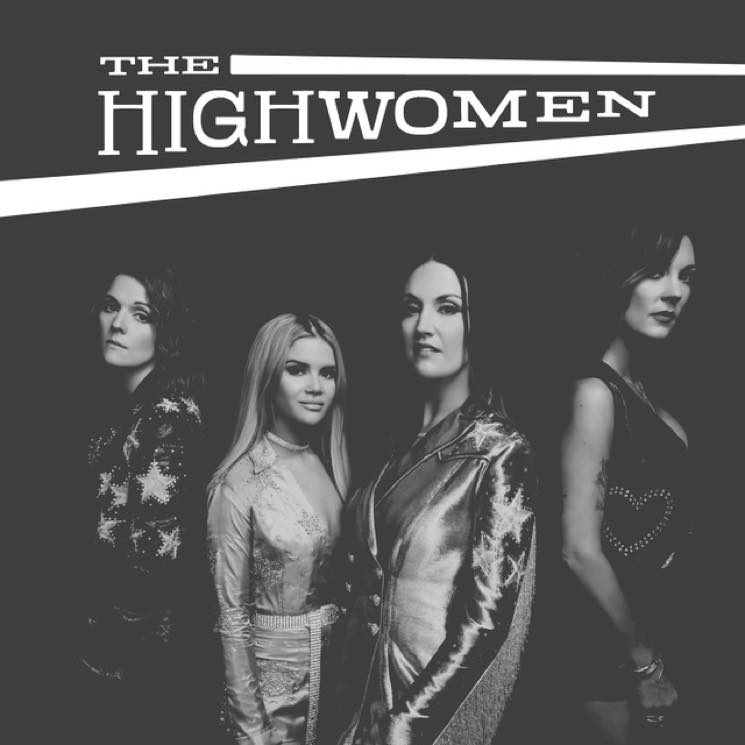

The Highwomen came to be in 2016, when Amanda Shires had the idea to put together an all-female country supergroup, partly in response to the prevalent gender bias of country music radio. Maren Morris, Natalie Hemby and Brandi Carlile gradually joined Shires and the group project was a go.

But the Highwomen want to be more than a musical supergroup. As Carlile explained in a Rolling Stone interview, the Highwomen want to be "a movement." "The Highwomen has become an adjective for any transcendent women's group," she said. "For anyone who wants to step aside and amplify the women to the left and right, and not compete."

The camaraderie that Carlile denotes as the ethos of the Highwomen is the heart of their debut record. It's felt most intensely on the harmonious ballad "Crowded Table," where the band advocate for inclusiveness and kindness: "everyone belongs," they repeat. On the bluesy "Don't Call Me," the Highwomen come together to fend off a dirtbag, and on the album's catchy, anthemic single, "Redesigning Women," they celebrate powerful women who do it all, "raisin' eyebrows and a new generation."

The Highwomen is steeped in country traditions and with it, a good dose of corniness, like "Heaven Is a Honky Tonk," which could be paired perfectly with a wagon wheel-adorned bar, or the Morris-led, radio-ready track "Loose Change." But like any good Elvis festival, there's a lot of fun to be had amongst the corn.

The album is at its best when the Highwomen subvert country tropes. On the opening track, "Highwomen," they nod to their namesake and put their own spin on "Highwayman," a song by the 1980s country supergroup the Highwaymen, made up of Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson. The original song featured each band member channelling a different macho, all-American hero who died in his line of work. The Highwomen's version follows women who have been persecuted and killed throughout history — a doctor, for instance or a Freedom Rider who is embodied by guest vocalist, and British country-soul singer-songwriter, Yola — and the resulting track is breathtaking.

Midway through the record, on "If She Ever Leaves Me," Carlile belts out a love ballad for the ages. In this magnificently queer country song, a woman reflects on her love for another woman while imagining losing her. But, addressing a man who is probably a lot like the male country music traditionalist rolling his eyes at the idea of the Highwomen, Carlile sharply guarantees that, "if she ever gives her careful heart to somebody new, well it won't be for a cowboy like you."

The Highwomen arrives when various country artists (Kacey Musgraves, Lil Nas X, Orville Peck and all of the Highwomen individually) are offering stories that are distinct from the genre's predominately straight white male narratives. The album is both a call for change and a celebration of women in country music. At the Highwomen's table, chairs are left empty and they encourage anybody who doesn't see themselves in country music to take a seat and to tell their own story.

(Low Country Sound / Elektra)But the Highwomen want to be more than a musical supergroup. As Carlile explained in a Rolling Stone interview, the Highwomen want to be "a movement." "The Highwomen has become an adjective for any transcendent women's group," she said. "For anyone who wants to step aside and amplify the women to the left and right, and not compete."

The camaraderie that Carlile denotes as the ethos of the Highwomen is the heart of their debut record. It's felt most intensely on the harmonious ballad "Crowded Table," where the band advocate for inclusiveness and kindness: "everyone belongs," they repeat. On the bluesy "Don't Call Me," the Highwomen come together to fend off a dirtbag, and on the album's catchy, anthemic single, "Redesigning Women," they celebrate powerful women who do it all, "raisin' eyebrows and a new generation."

The Highwomen is steeped in country traditions and with it, a good dose of corniness, like "Heaven Is a Honky Tonk," which could be paired perfectly with a wagon wheel-adorned bar, or the Morris-led, radio-ready track "Loose Change." But like any good Elvis festival, there's a lot of fun to be had amongst the corn.

The album is at its best when the Highwomen subvert country tropes. On the opening track, "Highwomen," they nod to their namesake and put their own spin on "Highwayman," a song by the 1980s country supergroup the Highwaymen, made up of Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson. The original song featured each band member channelling a different macho, all-American hero who died in his line of work. The Highwomen's version follows women who have been persecuted and killed throughout history — a doctor, for instance or a Freedom Rider who is embodied by guest vocalist, and British country-soul singer-songwriter, Yola — and the resulting track is breathtaking.

Midway through the record, on "If She Ever Leaves Me," Carlile belts out a love ballad for the ages. In this magnificently queer country song, a woman reflects on her love for another woman while imagining losing her. But, addressing a man who is probably a lot like the male country music traditionalist rolling his eyes at the idea of the Highwomen, Carlile sharply guarantees that, "if she ever gives her careful heart to somebody new, well it won't be for a cowboy like you."

The Highwomen arrives when various country artists (Kacey Musgraves, Lil Nas X, Orville Peck and all of the Highwomen individually) are offering stories that are distinct from the genre's predominately straight white male narratives. The album is both a call for change and a celebration of women in country music. At the Highwomen's table, chairs are left empty and they encourage anybody who doesn't see themselves in country music to take a seat and to tell their own story.