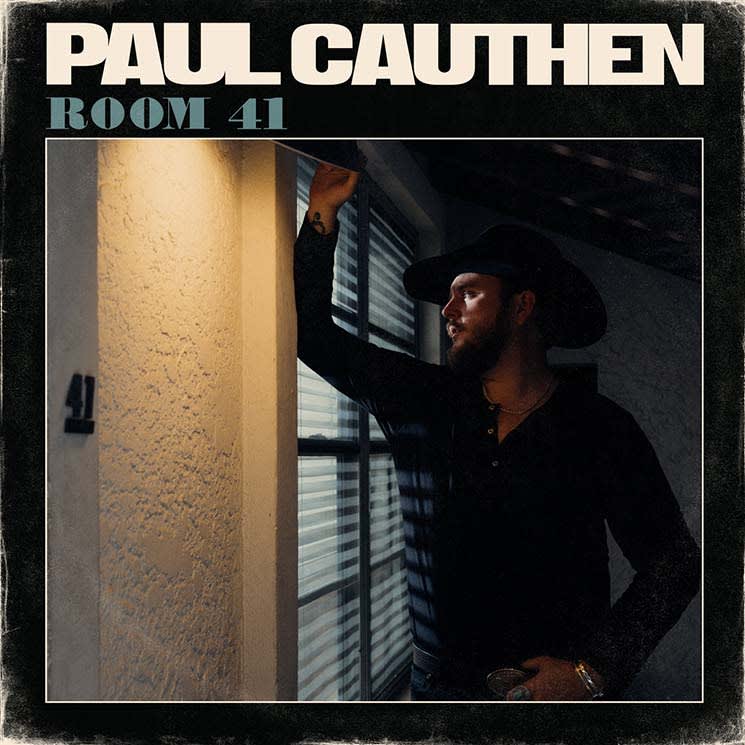

Paul Cauthen claims that making Room 41 nearly killed him; according to the album's liner notes, Cauthen wrote the album during the "harrowing" two-year period he lived in Dallas's Belmont Hotel, embarking on a "white-knuckle journey to the brink and back."

Is Room 41 heart-wrenching? Sometimes. Does the album reflect living out of a hotel room and doing a bunch of drugs? Sure. Is it a groundbreaking? No. This kind of "outlaw country" genre experimentation has been done before, and frankly, has been done better.

Dubbed "Big Velvet" for his "smooth baritone voice," Cauthen's vocals are gorgeous; his rich vibrato invites comparisons to Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard. His passionate pleas in "Give 'Em Peace" and "Holy Ghost Fire" deliver genuine goosebumps. Unfortunately, Cauthen's vocals are the only thing "country" in the album, and often sound out of place among hip-hop beats or funk-infused B3 organ solos.

Room 41 serves as a cautionary tale against unrestrained creativity: Cauthen blends so many styles, he doesn't sound like anything. The album is over-produced. Its concept — the romanticizing of drug abuse for the sake of artistry — is over-done. Cauthen may label himself "outlaw country," but the album lacks the frank honesty of Chris Stapleton, the tongue-in-cheek awareness of David Allan Coe, and the authenticity of Hank 3.

Cauthen's fans will probably find something of value here, but those looking for a fresh take on alt-country will be disappointed.

(Lightning Rod)Is Room 41 heart-wrenching? Sometimes. Does the album reflect living out of a hotel room and doing a bunch of drugs? Sure. Is it a groundbreaking? No. This kind of "outlaw country" genre experimentation has been done before, and frankly, has been done better.

Dubbed "Big Velvet" for his "smooth baritone voice," Cauthen's vocals are gorgeous; his rich vibrato invites comparisons to Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings and Merle Haggard. His passionate pleas in "Give 'Em Peace" and "Holy Ghost Fire" deliver genuine goosebumps. Unfortunately, Cauthen's vocals are the only thing "country" in the album, and often sound out of place among hip-hop beats or funk-infused B3 organ solos.

Room 41 serves as a cautionary tale against unrestrained creativity: Cauthen blends so many styles, he doesn't sound like anything. The album is over-produced. Its concept — the romanticizing of drug abuse for the sake of artistry — is over-done. Cauthen may label himself "outlaw country," but the album lacks the frank honesty of Chris Stapleton, the tongue-in-cheek awareness of David Allan Coe, and the authenticity of Hank 3.

Cauthen's fans will probably find something of value here, but those looking for a fresh take on alt-country will be disappointed.