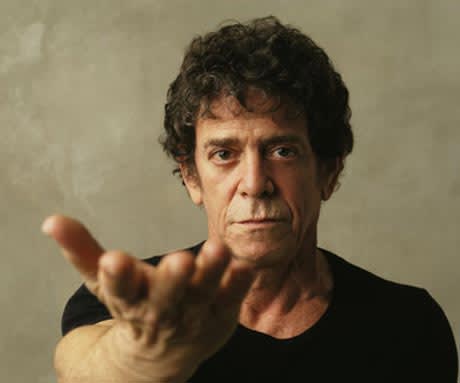

To set the scene: Lou Reed and director Julian Schnabel came to the Toronto International Film Festival in early September for the North American premiere of Lou Reeds Berlin (Schnabel was also here for his new feature film, Le Scaphandre et Le Papillon - The Bell And The Butterfly). The concert film was shot last December at Reeds New York City performances of his notorious 1973 album, Berlin. Reed has long been known as one of the toughest, most intimidating interviewees in rock, as this scribe can attest. Time and perhaps tai chi have seemingly mellowed the enfant terrible. In Toronto, the fit-looking 65 year old sat down for a "roundtable interview with six international journalists. Heres how the conversation went.

Was performing this live for the first time a relief?

I dont understand the question.

You put a lot of energy into the album, and it wasnt critically acclaimed, and now you performed it for the first time. Are you relieved as an artist to finally have brought it to the stage? An artist wants to get his work out there, right?

You know, just to be clear, Ive always loved that album. What critics say means absolutely nothing to me. I worked with some really good people, and we really loved that album. No one can like everything you do, because of, whatever, who knows? Ive never really figured that particular thing out, how you make people like things. But we always loved it. We had originally wanted to stage it and we never had the opportunity to do that. It was great to get that opportunity.

How did that come about?

A friend of mine named Susan Feldman runs a place [in Brooklyn] called St. Anns Warehouse. Before that, it was St. Anns Church. She has always been asking me to perform Berlin. One day I just thought, "That would be the greatest fun, and we set about to do it.

Was it important to have some of the key collaborators back, like producer Bob Ezrin and guitarist Steve Hunter?

Oh yes. Itd have been really difficult not to have Bob or Steve there.

When did Antony [of Antony and the Johnsons] become involved?

Very early on. I asked if hed like to become part of the choir, run the choir and do background vocals.

Could you explain your state of mind back when you wrote Berlin?

I cant, and I wouldnt anyway.

How was it to bring the material into the present?

I didnt have to do anything. It is about jealousy. You ever been jealous? Its about jealousy.

Has that feeling ever changed for you, in 30 years?

I really dont understand that. How would I know?

The album may not have thrilled the critics, but it clearly inspired other artists. Here at the Festival there are two Joy Division films, and both acknowledge you as an influence and inspiration for that band and Ian Curtis. Is that gratifying?

Thats great. I think it is great if anybody responds to the music. I try really hard, I put it out there, and I always hope they like it. I cant do anything if they dont. Im not writing for critics. Im writing for myself and for other people, then I never listen to it. Why would I listen to myself, when I could listen to new things? So when you ask me a lot about old things, I dont know how to respond to you. If you think I sit around thinking about that, its a mistake. I dont understand who you think does that.

Was it difficult to return to those emotions after 30 years?

Do you know what writing is? What acting is? It sounds pretentious, but I thought about Othello. Now youre talking about jealousy. Iago and Desdemona. How can Berlin be a twig on that tree? If you want to know about jealousy, go read Othello, or get a DVD of it. Dont ask me.

Julian Schnabel has said that Berlin always had a very important place in his heart. Were you aware of that?

He has told me that, over and over. Every Tuesday at nine.

Julian used the phrase "a soundtrack to my life. I bought the album in 1973 and wasnt aware it wasnt a critical success. There are phrases in the songs that just keep coming back to me. One of them is the phrase "Im just the waterboy, the real game is over here. Can you explain that?

Thats funny. We just went over a whole thing about the translation of the film for Venice. Usually I stay away from sports and street vernacular, because I dont want to date it. By the time something comes out, language has changed. I was hoping to be around for a while. Like maybe when you write a column, you try not to use a phrase that one month later will sound very old fashioned. Anyway, the waterboy in American sports, pro football, is a guy whos not on the team. Hes a younger guy who sweeps up, brings the players water, but hes not in the game. And yes the metaphor is for someone whos ineffectual, whos impotent.

Youve come up with albums that are somehow inspired by New York or Berlin. If there was a third place to inspire a song cycle, what would it be?

I was asked that before. I was thinking about India. I just saw a movie in New York, at the Cinema Village on 12th Street, but I cant recall the title. It was about a 14th century famous Buddhist yogi mystic/magician/sorcerer. One of their great mythological characters. Set in the mountains of Tibet and it was just amazing. I have done an album of meditation music.

Now the city of Berlin is a unique place. How was it for you, going back there to perform?

Keep in mind that when I wrote Berlin, I had never been there. I wasnt evoking anything. I went to Berlin after I wrote that album, when there still was a Wall. I have friends there; its a very cultural city. So it was interesting, what would Berlin think of Berlin?

What did you think of Julian using his family in the film? [Lola Schnabel made a short film of Caroline integrated in it].

They were really good, werent they? Yes and Alejandro [Garmendia, who contributed a short film of floating furniture]. His work was just amazing. We played some of the music from the old Berlin album against his video, that his brother-in-law made, and it was astonishing. Lola is no slouch! It reminded me a lot of what I liked best about the Exploding Plastic Inevitable with Warhol. The mix of film and colours and sound and things coming in and out of focus. It reminded me of that. It was incredibly beautiful, and it has Julians energy, which is a palpable thing. It is real and there it is on the screen. You need that energy to keep up with the music.

Why did you want to make a film of this?

Because we thought it was beautiful. Is that a good enough reason?

How about the scenes with the character Caroline? Did that correspond with your feelings?

We went through a lot, finding someone who could have that sort of attractive, dangerous quality, that is just going to be trouble.

Was Caroline a composite or a real person?

A composite, the worst of a number of people (laughs), all mixed into one. It is interesting with writing. Pick here, pick there. the real thing is not really that interesting, so you make it. Take four or five women on a bad day, and that makes Caroline. Then you write about her. What else can you do? Its the only way out.

How long did it take to write Berlin?

I dont know. If you count thinking, a long time. Actual physical writing? Very quick. Thinking? Not very quick.

What are you writing at present?

I have a thing called Purity, another electronic thing I want to do. Ive been putting this music to a DVD, with a guitar and processing, for a DVD of my chen tai chi instructor. I wanted to have modern music for the martial arts, not phony Chinese music. That same stuff, the Chinese bells. This is electronic, but to match what is going on. And I just recorded a thing with a band called the Killers, where I put on a guitar and a vocal. I like playing guitar for other people a lot. I like being in the back. Let some other guy go up front and answer all these questions.

I caught your London show earlier this year. Seemed you were in full flight then.

Yes, we really hit a pocket there. We had the choir and strings. These guys can play anything. I will never make fun of the English again.

Was performing this live for the first time a relief?

I dont understand the question.

You put a lot of energy into the album, and it wasnt critically acclaimed, and now you performed it for the first time. Are you relieved as an artist to finally have brought it to the stage? An artist wants to get his work out there, right?

You know, just to be clear, Ive always loved that album. What critics say means absolutely nothing to me. I worked with some really good people, and we really loved that album. No one can like everything you do, because of, whatever, who knows? Ive never really figured that particular thing out, how you make people like things. But we always loved it. We had originally wanted to stage it and we never had the opportunity to do that. It was great to get that opportunity.

How did that come about?

A friend of mine named Susan Feldman runs a place [in Brooklyn] called St. Anns Warehouse. Before that, it was St. Anns Church. She has always been asking me to perform Berlin. One day I just thought, "That would be the greatest fun, and we set about to do it.

Was it important to have some of the key collaborators back, like producer Bob Ezrin and guitarist Steve Hunter?

Oh yes. Itd have been really difficult not to have Bob or Steve there.

When did Antony [of Antony and the Johnsons] become involved?

Very early on. I asked if hed like to become part of the choir, run the choir and do background vocals.

Could you explain your state of mind back when you wrote Berlin?

I cant, and I wouldnt anyway.

How was it to bring the material into the present?

I didnt have to do anything. It is about jealousy. You ever been jealous? Its about jealousy.

Has that feeling ever changed for you, in 30 years?

I really dont understand that. How would I know?

The album may not have thrilled the critics, but it clearly inspired other artists. Here at the Festival there are two Joy Division films, and both acknowledge you as an influence and inspiration for that band and Ian Curtis. Is that gratifying?

Thats great. I think it is great if anybody responds to the music. I try really hard, I put it out there, and I always hope they like it. I cant do anything if they dont. Im not writing for critics. Im writing for myself and for other people, then I never listen to it. Why would I listen to myself, when I could listen to new things? So when you ask me a lot about old things, I dont know how to respond to you. If you think I sit around thinking about that, its a mistake. I dont understand who you think does that.

Was it difficult to return to those emotions after 30 years?

Do you know what writing is? What acting is? It sounds pretentious, but I thought about Othello. Now youre talking about jealousy. Iago and Desdemona. How can Berlin be a twig on that tree? If you want to know about jealousy, go read Othello, or get a DVD of it. Dont ask me.

Julian Schnabel has said that Berlin always had a very important place in his heart. Were you aware of that?

He has told me that, over and over. Every Tuesday at nine.

Julian used the phrase "a soundtrack to my life. I bought the album in 1973 and wasnt aware it wasnt a critical success. There are phrases in the songs that just keep coming back to me. One of them is the phrase "Im just the waterboy, the real game is over here. Can you explain that?

Thats funny. We just went over a whole thing about the translation of the film for Venice. Usually I stay away from sports and street vernacular, because I dont want to date it. By the time something comes out, language has changed. I was hoping to be around for a while. Like maybe when you write a column, you try not to use a phrase that one month later will sound very old fashioned. Anyway, the waterboy in American sports, pro football, is a guy whos not on the team. Hes a younger guy who sweeps up, brings the players water, but hes not in the game. And yes the metaphor is for someone whos ineffectual, whos impotent.

Youve come up with albums that are somehow inspired by New York or Berlin. If there was a third place to inspire a song cycle, what would it be?

I was asked that before. I was thinking about India. I just saw a movie in New York, at the Cinema Village on 12th Street, but I cant recall the title. It was about a 14th century famous Buddhist yogi mystic/magician/sorcerer. One of their great mythological characters. Set in the mountains of Tibet and it was just amazing. I have done an album of meditation music.

Now the city of Berlin is a unique place. How was it for you, going back there to perform?

Keep in mind that when I wrote Berlin, I had never been there. I wasnt evoking anything. I went to Berlin after I wrote that album, when there still was a Wall. I have friends there; its a very cultural city. So it was interesting, what would Berlin think of Berlin?

What did you think of Julian using his family in the film? [Lola Schnabel made a short film of Caroline integrated in it].

They were really good, werent they? Yes and Alejandro [Garmendia, who contributed a short film of floating furniture]. His work was just amazing. We played some of the music from the old Berlin album against his video, that his brother-in-law made, and it was astonishing. Lola is no slouch! It reminded me a lot of what I liked best about the Exploding Plastic Inevitable with Warhol. The mix of film and colours and sound and things coming in and out of focus. It reminded me of that. It was incredibly beautiful, and it has Julians energy, which is a palpable thing. It is real and there it is on the screen. You need that energy to keep up with the music.

Why did you want to make a film of this?

Because we thought it was beautiful. Is that a good enough reason?

How about the scenes with the character Caroline? Did that correspond with your feelings?

We went through a lot, finding someone who could have that sort of attractive, dangerous quality, that is just going to be trouble.

Was Caroline a composite or a real person?

A composite, the worst of a number of people (laughs), all mixed into one. It is interesting with writing. Pick here, pick there. the real thing is not really that interesting, so you make it. Take four or five women on a bad day, and that makes Caroline. Then you write about her. What else can you do? Its the only way out.

How long did it take to write Berlin?

I dont know. If you count thinking, a long time. Actual physical writing? Very quick. Thinking? Not very quick.

What are you writing at present?

I have a thing called Purity, another electronic thing I want to do. Ive been putting this music to a DVD, with a guitar and processing, for a DVD of my chen tai chi instructor. I wanted to have modern music for the martial arts, not phony Chinese music. That same stuff, the Chinese bells. This is electronic, but to match what is going on. And I just recorded a thing with a band called the Killers, where I put on a guitar and a vocal. I like playing guitar for other people a lot. I like being in the back. Let some other guy go up front and answer all these questions.

I caught your London show earlier this year. Seemed you were in full flight then.

Yes, we really hit a pocket there. We had the choir and strings. These guys can play anything. I will never make fun of the English again.