"I didn't want to play music anymore. I needed to think maybe I was gonna open a bookstore or learn how to surf and never come back."

It was 2008 and Leslie Feist, Canada's indie pop darling (and occasional Broken Social Scenester) was ready to quit being Feist. For seven years the road was her home, thanks to non-stop touring in support of back-to-back platinum-selling albums Let It Die and The Reminder. During that time, she taught Elmo her famed "1234" song on Sesame Street, provided a soundtrack to the great iPod explosion of 2007, and won a Grammy (as part of Stephen Colbert's 2008 A Colbert Christmas: The Greatest Gift of All).

"I just wanted to stop and be in one place for more than a day," Feist says. "It's like the way some people take a vacation and travelling to them is a novelty. They cram all their curiosity into seeing something they've never seen, or unwinding and laying still or whatever you seek out in your vacation. To me, coming home and trying to be domestic was equally alien. I still haven't figured it out. I just came back from France and I was home for about two weeks before I noticed, like, why is there no food in my house, why are there are no groceries? There are spiders in the sink. I still don't know how to live in a place even when I'm living in it."

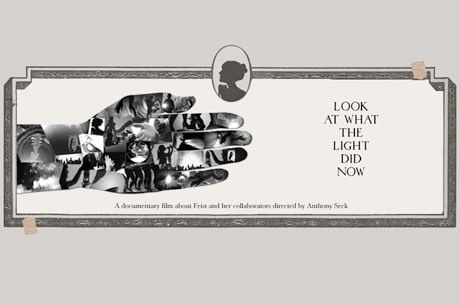

She didn't become a homemaking goddess during her self-imposed exile, but Feist managed to achieve a certain domestic bliss: she sewed, harvested and devoured at least one crop of tomatoes, and adopted two dogs so she could bask in the warmth of "furry love crawling all over" her. Though she eschewed the road, she indulged in periodic side projects: a documentary about the making of The Reminder called Look At What the Light Did Now, recordings with Wilco and Beck, and an experimental choral piece using puppets with visual artist Clea Minaker for Casteliers, Montreal's contemporary puppet festival. Despite the soil on her fingertips and the bounty of distractions, she also found herself engaged in a lengthy staring contest with her guitar, which sat perched in the corner of her room.

The guitar won.

Metals, Feist's fourth album, hits stores October 4. Some of its influences sound familiar, but there are dramatic forays into thumping beats, shouted choruses, and punched-up rock riffs. This is what her time off wrought: a fresh start.

"When I first got off the road, it was of the mindset that I don't care about the future, I just care that today I am not on tour anymore," Feist says. "I'm not picking up that guitar over there and it's sort of squinting at me and I'm going to squint back at it but I'm not going to play it. It's not that I hated music — I wanted to do other things, some normal stuff. I took enough time off that there was a fresh, mental clean slate. That guitar I was squinting at, eventually I picked it up. Eventually I got curious about it again. And then not only was I curious but I got completely ignited and I was back."

Feist wrote the album last fall, locking herself inside a derelict garage in her own backyard. She soundproofed the space and covered up the windows, creating her own deprivation tank in which she erected a little altar decorated with postcards alongside her piano, a floor tom and a broken, vintage Sears Roebuck guitar and amp. It was a guitar she didn't know very well, but after years of treading water — revisiting the same music, songs, and her beloved Guild Starfire — she felt it was time for a new conversation.

It was in the autumn that I really started, in September or October 2010, when the film [Look At What the Light Did Now] was done," Feist says. "I was so sick of looking at the past, via that film, that I really was much more curious about looking into the future, which I've never done. I'm pretty nostalgic. I've never been interested in the future, but I just got whiplash from too much looking back."

For some artists, moving forward means working with new producers and collaborators, creating new conversations with actual people, not just guitars. But, when one's long-time collaborators and friends are the chameleon-like musicians/producers Chilly Gonzales and Mocky, vocal shorthand can spark a much wilder reinvention.

Of all the people on the planet, I knew they were the last two on earth that would want me to recreate Reminder-type tones," Feist says. "Like, 'Yeah, The Reminder, that was ten seconds in the total story, so why would we?' I knew there was going to be the chance to really begin again. This record is not about recreating a past or reacting to it, too much."

Metals definitely indicates a forward momentum. Sonically, it represents the connective tissue between Feist's past and present, with echoes of whisper-light whimsical pop and jazz, and achingly beautiful moments of piano threaded with crunchier guitars, throbbingly sexy drums, and twinkles of flute.

Gonzales has nothing but praise for the ways in which his old friend has grown as a musician. In an email from his home base in Paris, he offered his analysis of Metals: "The songwriting is less conventional than before. She's being much bolder about getting away from default song structures than I could probably ever be. The songs sound simple but are actually more complex than one would think. She would play me a sketch, and I would feel as if I had understood the song — but when I tried to play along, I noticed a lot of counter-intuitive details. Her singing and guitar playing are just off the charts now since she toured so much. Having so-called 'credibility' — my fingers can hardly type the words — and big success is a huge boost to her confidence. Between the first two albums she went far into 'owning' every note of the album and was rewarded by all that love — so the leap between [The Reminder] and [Metals] is a bigger and more sure-footed leap. The wind is at her back now."

The only person who might not know that is Feist herself. After all, this success is still relatively new. And worldwide name recognition can't eliminate the inescapable truth that creativity is a tempestuous mistress and she never knows when, or if, inspiration will strike.

Every song I write I think is going to be the last one," Feist admits, laughing. "It's as if I'm of ten minds and I'm standing in a circle and each of me takes a tiny baby step closer to the centre of the circle and each of me is holding something in their hands until we all get to the very centre and we all converge and it's sort of hard to know what the hell is going on. Sonically, thematically or a little totem, an oracular totem that I kind of superstitiously fill with meaning — all the things that sort of converge to become a song, are weirdly, totally unknown. Of my minds, it sort of seems to be a collective process in terms of the way I — I'm totally alone, but it's not a quiet, calm place when I'm alone. There's a lot of ruckus in there."

Occasionally the din is coupled with old-fashioned self-esteem issues, which surface even when she's working with two of her closest friends.

I don't know music theory," she says. "Mocky and Gonzo both have degrees in music and they would roll their eyes if they were to read this — I mean, I know what both have achieved has nothing to do with the fact that they know theory — but as someone who's never learned it, it's an intimidating skill to not have in a room full of people who have it, even if they aren't consciously accessing that stuff. Say I'm showing them 'Graveyard,' a song I wrote alone in the room, they have their interpretive conference like, 'Yeah, on the B minor we should probably not have the F sharp because that will make it too major,' where all I can contribute is, 'Wait that resolves it too much, no, no, that sounds like an unfinished thought, this has to still be a question by the end!'"

She laughs as she says this, but Gonzales insists that Feist's intuitive approach to songwriting is a credit, not a detriment.

Leslie has a huge part of her creativity that is feeling-based so she pushes me to get to that emotional intensity," he offers. "She was the A&R for Solo Piano, what we called 'PrePro RepCon' for pre-production repertoire consultant. She helped choose the songs, which takes of the songs, and the album order. The whole thing was strongly under her influence and it's my best-loved album, I think, and that's largely to her credit."

Feist calls it speaking in purples and mauves, and she's grateful to have this shorthand between them. She believes that while she may write the songs, they're really just a starting point, a common ground for the three of them before they begin arranging.

It's why I credit the arrangement, because between the writing and the producing there is that part of things," Feist explains. "When you're a solo artist, you're bringing people in who don't normally play with you, so those decisions on what the bass is going to do and how the drums are going to interact, all of that stuff, is kind of a much more conscious effort of arrangement. Not in a write-it-down-on-musical-staff or something, but it's definitely a conscious part of the equation. That's inventing the landscape, which we did together."

After arranging in January, Feist, Gonzales, Mocky, percussionist Dean Stone and keyboardist Brian LeBarto holed up in Big Sur, California, and recorded the album in a little over two weeks. From embracing music again to wrapping Metals, it took just five months — a privileged position for any musician. And Feist's good fortune is not lost on her. Her gratitude and delight at making another record is genuine: 15 years ago, she didn't know if she would ever sing again due to major vocal cord strain from her five years touring with all-girl punk band Placebo.

"Other singers, we roll our eyes about it all the time because there isn't a formula to make it all work out: You have to take flights, you have to sleep in the wrong kinds of environments, you have to maybe not sleep at all sometimes," she says. But instead of lingering on the what-ifs, she clings to a realization she arrived at many years ago on the road. "I was in Manchester, that drench-y, cold place, sick and unhappy and playing a solo show at some university. I remember having the conscious thought that there's nothing I can do right now except use whatever's left and use it with the same intention, which isn't necessarily about hitting notes. It was just a moment of freeing myself from any type of precision-chasing."

But, that threat to her livelihood and her main creative outlet remains a very real ghost that — fresh start or not — lingers over every decision she makes to this day.

I think about that a lot [not being able to sing]," Feist admits. "There's a kind of helplessness you feel, like why do you wake up one Tuesday where I just can't [sing], I don't have it. I'm exhausted or been in an air-conditioned room and I'm just rendered completely hobbled. It has so little to do with what I can control. It's made me obsessively into guitar tone because you can touch something and move a knob and you can control it with your hands. It's just a freedom. I always say to people in my band that they can go out and have a conversation and drinks or whatever and I'm kind of like the maimed, lonely singer, drinking tons of water, watching some movie in the bus, because it is something I have to be careful about. I don't know what I'd do if I couldn't [sing]."

It was 2008 and Leslie Feist, Canada's indie pop darling (and occasional Broken Social Scenester) was ready to quit being Feist. For seven years the road was her home, thanks to non-stop touring in support of back-to-back platinum-selling albums Let It Die and The Reminder. During that time, she taught Elmo her famed "1234" song on Sesame Street, provided a soundtrack to the great iPod explosion of 2007, and won a Grammy (as part of Stephen Colbert's 2008 A Colbert Christmas: The Greatest Gift of All).

"I just wanted to stop and be in one place for more than a day," Feist says. "It's like the way some people take a vacation and travelling to them is a novelty. They cram all their curiosity into seeing something they've never seen, or unwinding and laying still or whatever you seek out in your vacation. To me, coming home and trying to be domestic was equally alien. I still haven't figured it out. I just came back from France and I was home for about two weeks before I noticed, like, why is there no food in my house, why are there are no groceries? There are spiders in the sink. I still don't know how to live in a place even when I'm living in it."

She didn't become a homemaking goddess during her self-imposed exile, but Feist managed to achieve a certain domestic bliss: she sewed, harvested and devoured at least one crop of tomatoes, and adopted two dogs so she could bask in the warmth of "furry love crawling all over" her. Though she eschewed the road, she indulged in periodic side projects: a documentary about the making of The Reminder called Look At What the Light Did Now, recordings with Wilco and Beck, and an experimental choral piece using puppets with visual artist Clea Minaker for Casteliers, Montreal's contemporary puppet festival. Despite the soil on her fingertips and the bounty of distractions, she also found herself engaged in a lengthy staring contest with her guitar, which sat perched in the corner of her room.

The guitar won.

Metals, Feist's fourth album, hits stores October 4. Some of its influences sound familiar, but there are dramatic forays into thumping beats, shouted choruses, and punched-up rock riffs. This is what her time off wrought: a fresh start.

"When I first got off the road, it was of the mindset that I don't care about the future, I just care that today I am not on tour anymore," Feist says. "I'm not picking up that guitar over there and it's sort of squinting at me and I'm going to squint back at it but I'm not going to play it. It's not that I hated music — I wanted to do other things, some normal stuff. I took enough time off that there was a fresh, mental clean slate. That guitar I was squinting at, eventually I picked it up. Eventually I got curious about it again. And then not only was I curious but I got completely ignited and I was back."

Feist wrote the album last fall, locking herself inside a derelict garage in her own backyard. She soundproofed the space and covered up the windows, creating her own deprivation tank in which she erected a little altar decorated with postcards alongside her piano, a floor tom and a broken, vintage Sears Roebuck guitar and amp. It was a guitar she didn't know very well, but after years of treading water — revisiting the same music, songs, and her beloved Guild Starfire — she felt it was time for a new conversation.

It was in the autumn that I really started, in September or October 2010, when the film [Look At What the Light Did Now] was done," Feist says. "I was so sick of looking at the past, via that film, that I really was much more curious about looking into the future, which I've never done. I'm pretty nostalgic. I've never been interested in the future, but I just got whiplash from too much looking back."

For some artists, moving forward means working with new producers and collaborators, creating new conversations with actual people, not just guitars. But, when one's long-time collaborators and friends are the chameleon-like musicians/producers Chilly Gonzales and Mocky, vocal shorthand can spark a much wilder reinvention.

Of all the people on the planet, I knew they were the last two on earth that would want me to recreate Reminder-type tones," Feist says. "Like, 'Yeah, The Reminder, that was ten seconds in the total story, so why would we?' I knew there was going to be the chance to really begin again. This record is not about recreating a past or reacting to it, too much."

Metals definitely indicates a forward momentum. Sonically, it represents the connective tissue between Feist's past and present, with echoes of whisper-light whimsical pop and jazz, and achingly beautiful moments of piano threaded with crunchier guitars, throbbingly sexy drums, and twinkles of flute.

Gonzales has nothing but praise for the ways in which his old friend has grown as a musician. In an email from his home base in Paris, he offered his analysis of Metals: "The songwriting is less conventional than before. She's being much bolder about getting away from default song structures than I could probably ever be. The songs sound simple but are actually more complex than one would think. She would play me a sketch, and I would feel as if I had understood the song — but when I tried to play along, I noticed a lot of counter-intuitive details. Her singing and guitar playing are just off the charts now since she toured so much. Having so-called 'credibility' — my fingers can hardly type the words — and big success is a huge boost to her confidence. Between the first two albums she went far into 'owning' every note of the album and was rewarded by all that love — so the leap between [The Reminder] and [Metals] is a bigger and more sure-footed leap. The wind is at her back now."

The only person who might not know that is Feist herself. After all, this success is still relatively new. And worldwide name recognition can't eliminate the inescapable truth that creativity is a tempestuous mistress and she never knows when, or if, inspiration will strike.

Every song I write I think is going to be the last one," Feist admits, laughing. "It's as if I'm of ten minds and I'm standing in a circle and each of me takes a tiny baby step closer to the centre of the circle and each of me is holding something in their hands until we all get to the very centre and we all converge and it's sort of hard to know what the hell is going on. Sonically, thematically or a little totem, an oracular totem that I kind of superstitiously fill with meaning — all the things that sort of converge to become a song, are weirdly, totally unknown. Of my minds, it sort of seems to be a collective process in terms of the way I — I'm totally alone, but it's not a quiet, calm place when I'm alone. There's a lot of ruckus in there."

Occasionally the din is coupled with old-fashioned self-esteem issues, which surface even when she's working with two of her closest friends.

I don't know music theory," she says. "Mocky and Gonzo both have degrees in music and they would roll their eyes if they were to read this — I mean, I know what both have achieved has nothing to do with the fact that they know theory — but as someone who's never learned it, it's an intimidating skill to not have in a room full of people who have it, even if they aren't consciously accessing that stuff. Say I'm showing them 'Graveyard,' a song I wrote alone in the room, they have their interpretive conference like, 'Yeah, on the B minor we should probably not have the F sharp because that will make it too major,' where all I can contribute is, 'Wait that resolves it too much, no, no, that sounds like an unfinished thought, this has to still be a question by the end!'"

She laughs as she says this, but Gonzales insists that Feist's intuitive approach to songwriting is a credit, not a detriment.

Leslie has a huge part of her creativity that is feeling-based so she pushes me to get to that emotional intensity," he offers. "She was the A&R for Solo Piano, what we called 'PrePro RepCon' for pre-production repertoire consultant. She helped choose the songs, which takes of the songs, and the album order. The whole thing was strongly under her influence and it's my best-loved album, I think, and that's largely to her credit."

Feist calls it speaking in purples and mauves, and she's grateful to have this shorthand between them. She believes that while she may write the songs, they're really just a starting point, a common ground for the three of them before they begin arranging.

It's why I credit the arrangement, because between the writing and the producing there is that part of things," Feist explains. "When you're a solo artist, you're bringing people in who don't normally play with you, so those decisions on what the bass is going to do and how the drums are going to interact, all of that stuff, is kind of a much more conscious effort of arrangement. Not in a write-it-down-on-musical-staff or something, but it's definitely a conscious part of the equation. That's inventing the landscape, which we did together."

After arranging in January, Feist, Gonzales, Mocky, percussionist Dean Stone and keyboardist Brian LeBarto holed up in Big Sur, California, and recorded the album in a little over two weeks. From embracing music again to wrapping Metals, it took just five months — a privileged position for any musician. And Feist's good fortune is not lost on her. Her gratitude and delight at making another record is genuine: 15 years ago, she didn't know if she would ever sing again due to major vocal cord strain from her five years touring with all-girl punk band Placebo.

"Other singers, we roll our eyes about it all the time because there isn't a formula to make it all work out: You have to take flights, you have to sleep in the wrong kinds of environments, you have to maybe not sleep at all sometimes," she says. But instead of lingering on the what-ifs, she clings to a realization she arrived at many years ago on the road. "I was in Manchester, that drench-y, cold place, sick and unhappy and playing a solo show at some university. I remember having the conscious thought that there's nothing I can do right now except use whatever's left and use it with the same intention, which isn't necessarily about hitting notes. It was just a moment of freeing myself from any type of precision-chasing."

But, that threat to her livelihood and her main creative outlet remains a very real ghost that — fresh start or not — lingers over every decision she makes to this day.

I think about that a lot [not being able to sing]," Feist admits. "There's a kind of helplessness you feel, like why do you wake up one Tuesday where I just can't [sing], I don't have it. I'm exhausted or been in an air-conditioned room and I'm just rendered completely hobbled. It has so little to do with what I can control. It's made me obsessively into guitar tone because you can touch something and move a knob and you can control it with your hands. It's just a freedom. I always say to people in my band that they can go out and have a conversation and drinks or whatever and I'm kind of like the maimed, lonely singer, drinking tons of water, watching some movie in the bus, because it is something I have to be careful about. I don't know what I'd do if I couldn't [sing]."