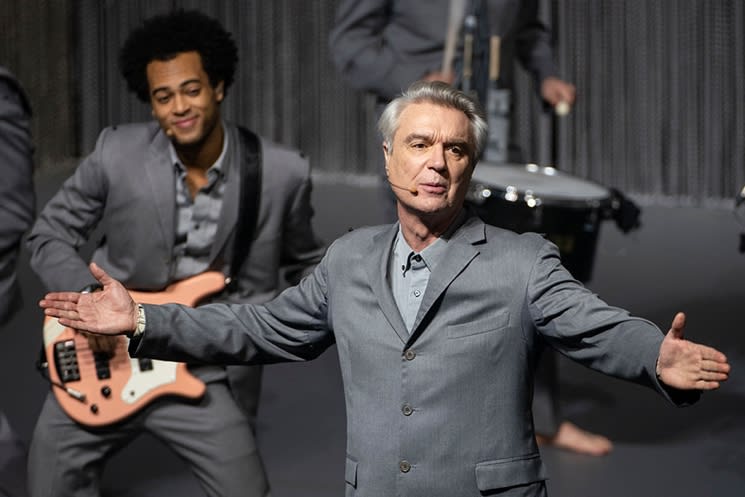

American Utopia has all the qualities of a great concert film: an accomplished director (Spike Lee), a fascinating performer with a rich musical catalogue (David Byrne), precise choreography (courtesy of Annie-B Parson), and perhaps most of all, energetic performances from powerhouse musicians. Shot in 2019, American Utopia intertwines artistic conventions from music, theatre and film in its presentation of David Byrne's Broadway stage show, in which he is joined by 11 musicians to present material from throughout his career, including his most recent album of the same name.

Its minimalist staging and gradual introduction of musicians onto the stage recalls another concert film, widely considered one of the greatest of its form, Jonathan Demme's Stop Making Sense (1984). That film captured the brilliantly strange magic of Talking Heads, the band Byrne spent most of his career performing with. Indeed, the legacies of both Talking Heads and Jonathan Demme loom over American Utopia, evidenced by the rapturous crowd responses to songs such as "Burning Down the House" and "Once in a Lifetime," and an explicit shoutout to Demme in the end credits. Much like Stop Making Sense, American Utopia is not simply a straightforward rendering of a concert, but stands on its own as a unique artistic project.

The film recalls the visual experimentation of Stop Making Sense, utilizing overhead shots and low angles to offer unique perspectives on the performers' various bodily formations. Where Stop Making Sense rendered bodies and objects strange through shadowy lighting, angular and awkward dance movements, and eccentric costumes such as Byrne's iconic big suit, American Utopia achieves somewhat similar aims through different means. Every onstage movement is perfectly and precisely planned, at times resulting in spectacular Busby Berkeley-esque formations, rendered all the more seamless by the performers' identical grey suits and bare feet. The camera elegantly swoops and glides around the stage, offering a decentralized field of vision where each musician is given an almost equal amount of time to shine and demonstrate their unique forms of artistry.

Byrne himself is the slightly awkward, off-kilter anchor of the piece, perhaps slightly less kinetic than in Stop Making Sense but no less compelling and energetic. At times, he seems incredulous at the audience's enthusiasm toward his every word, and is seemingly more interested in communicating the overarching artistic vision of American Utopia than presenting a career retrospective for purposes of validation or self-congratulation. From the opening moments of the film, with Byrne performing alone onstage, singing Hamlet-like to a model of a human brain about how each part functions and connects to each other ("Here"), he sets out to create an environment of positivity, connection, and collectivity.

American Utopia stages a vision of collaborative artistic creation, featuring musicians from different cultural backgrounds across intersecting gender, sexual and racial identities. The show's title raises questions about what a specifically American utopia might look like, and who has the power to even conceptualize it. Talking Heads were frequently attuned to political issues, lyrically referencing notions of class inequality, the American Dream, mass media and the government's continual obfuscations ("Our president's crazy / Did you hear what he said?" in "Making Flippy Floppy" seems forever relevant). In performing these songs — "Don't Worry About the Government," "Once in a Lifetime," "Slippery People" — Byrne thus brings them into contact with current political and social issues, and sheds light on their shifting meanings and continual relevance.

In the most explicitly political segment of the show, Byrne performs a rendition of Janelle Monáe's powerful protest song, "Hell You Talmbout." Byrne and the musicians forcefully name a multitude of victims of police brutality, including Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin and Emmett Till, demanding that the audience "say his/her name," while Lee cuts between the performance and images of the people named held up by their loved ones. This performance, along with a moment in the show where a projected image of Colin Kaepernick appears and the musicians take a knee, suggests that any utopia, any form of radical political or social change, must first acknowledge the violence and harm deeply rooted in the systems that came before. Yet this raises the question of what such gestures achieve, whether this is performative or surface-level activism, or if such confrontational theatrical performances are enough to inspire people toward real, tangible action.

Byrne acknowledges the awkwardness of an older white man such as himself performing a song written by a queer Black woman focused on the violence inflicted upon marginalized communities, and reassures the audience that he has Monáe's enthusiastic blessing. Byrne has always represented a form of brainy, slightly anxious, politically-minded musicianship, yet American Utopia showcases his softer side, especially in songs such as "Everybody's Coming to My House," in which he notes (perhaps reluctantly) how important it is to spent time with loved ones and friends. Indeed, the power and vitality of human connection is on full display here, where, for approximately two hours, the rest of the world falls away and all that is left is the dazzling force of music, movement and collaboration.

(HBO)Its minimalist staging and gradual introduction of musicians onto the stage recalls another concert film, widely considered one of the greatest of its form, Jonathan Demme's Stop Making Sense (1984). That film captured the brilliantly strange magic of Talking Heads, the band Byrne spent most of his career performing with. Indeed, the legacies of both Talking Heads and Jonathan Demme loom over American Utopia, evidenced by the rapturous crowd responses to songs such as "Burning Down the House" and "Once in a Lifetime," and an explicit shoutout to Demme in the end credits. Much like Stop Making Sense, American Utopia is not simply a straightforward rendering of a concert, but stands on its own as a unique artistic project.

The film recalls the visual experimentation of Stop Making Sense, utilizing overhead shots and low angles to offer unique perspectives on the performers' various bodily formations. Where Stop Making Sense rendered bodies and objects strange through shadowy lighting, angular and awkward dance movements, and eccentric costumes such as Byrne's iconic big suit, American Utopia achieves somewhat similar aims through different means. Every onstage movement is perfectly and precisely planned, at times resulting in spectacular Busby Berkeley-esque formations, rendered all the more seamless by the performers' identical grey suits and bare feet. The camera elegantly swoops and glides around the stage, offering a decentralized field of vision where each musician is given an almost equal amount of time to shine and demonstrate their unique forms of artistry.

Byrne himself is the slightly awkward, off-kilter anchor of the piece, perhaps slightly less kinetic than in Stop Making Sense but no less compelling and energetic. At times, he seems incredulous at the audience's enthusiasm toward his every word, and is seemingly more interested in communicating the overarching artistic vision of American Utopia than presenting a career retrospective for purposes of validation or self-congratulation. From the opening moments of the film, with Byrne performing alone onstage, singing Hamlet-like to a model of a human brain about how each part functions and connects to each other ("Here"), he sets out to create an environment of positivity, connection, and collectivity.

American Utopia stages a vision of collaborative artistic creation, featuring musicians from different cultural backgrounds across intersecting gender, sexual and racial identities. The show's title raises questions about what a specifically American utopia might look like, and who has the power to even conceptualize it. Talking Heads were frequently attuned to political issues, lyrically referencing notions of class inequality, the American Dream, mass media and the government's continual obfuscations ("Our president's crazy / Did you hear what he said?" in "Making Flippy Floppy" seems forever relevant). In performing these songs — "Don't Worry About the Government," "Once in a Lifetime," "Slippery People" — Byrne thus brings them into contact with current political and social issues, and sheds light on their shifting meanings and continual relevance.

In the most explicitly political segment of the show, Byrne performs a rendition of Janelle Monáe's powerful protest song, "Hell You Talmbout." Byrne and the musicians forcefully name a multitude of victims of police brutality, including Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin and Emmett Till, demanding that the audience "say his/her name," while Lee cuts between the performance and images of the people named held up by their loved ones. This performance, along with a moment in the show where a projected image of Colin Kaepernick appears and the musicians take a knee, suggests that any utopia, any form of radical political or social change, must first acknowledge the violence and harm deeply rooted in the systems that came before. Yet this raises the question of what such gestures achieve, whether this is performative or surface-level activism, or if such confrontational theatrical performances are enough to inspire people toward real, tangible action.

Byrne acknowledges the awkwardness of an older white man such as himself performing a song written by a queer Black woman focused on the violence inflicted upon marginalized communities, and reassures the audience that he has Monáe's enthusiastic blessing. Byrne has always represented a form of brainy, slightly anxious, politically-minded musicianship, yet American Utopia showcases his softer side, especially in songs such as "Everybody's Coming to My House," in which he notes (perhaps reluctantly) how important it is to spent time with loved ones and friends. Indeed, the power and vitality of human connection is on full display here, where, for approximately two hours, the rest of the world falls away and all that is left is the dazzling force of music, movement and collaboration.