"You ever feel just like your brain's been bolted to the wall?" Bob Dylan half-screams on the first version of "Can't Wait," captured in January 1997. "All the screws are tightening and you're cut off from it all / I don't know."

It's a scorching outtake, with Dylan biting into his cinematic verses, many of which he'd eventually alter, as the band blends a perfect amalgam of heft and space for a menacing "Ballad of a Thin Man" bounce. It starts innocently and evenly before the full spectrum of sound kicks in and Dylan launches into the vocal like a tiger, but then he doubts himself.

"I don't know." Really?

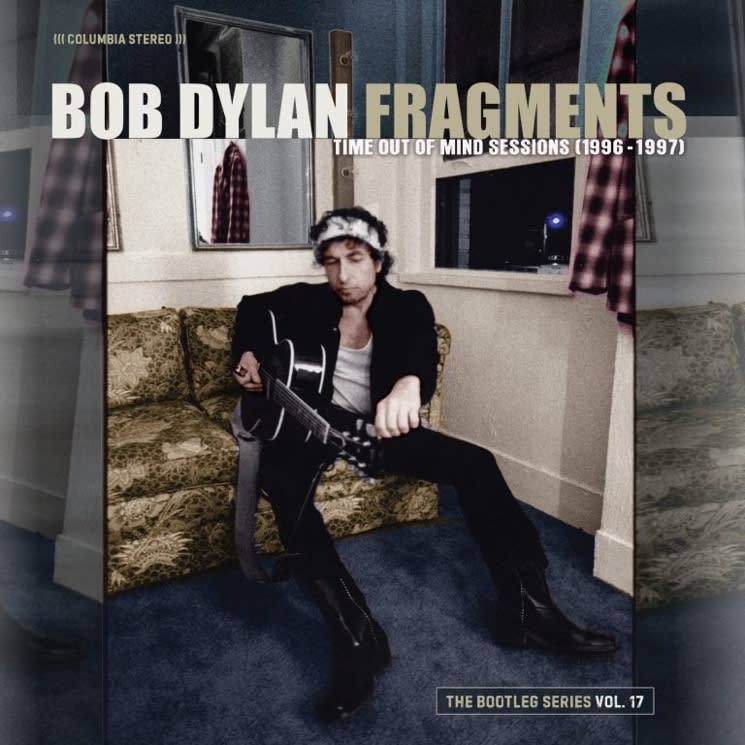

It's such a specifically certain circumstance to be unsure about, but then, counting a couple of live variations, there are five unique versions of "Can't Wait" on Fragments, the 17th volume of Dylan's generous Bootleg Series, which captures the sessions for 1997's Time Out of Mind, Dylan's 30th (and, to a certain generation of fans, best) album.

As such, this indispensable and revelatory treatment is as loving and comprehensive as can be, giving us a sense of how Dylan and his various collaborators nailed down these spooky, funny, hard songs pondering loneliness, independence and the end of one's days. Beyond the stellar players, Dylan's accomplices notably include producer Daniel Lanois and engineer Mark Howard, a Canadian tandem who helped Dylan give these wondrous songs their ambience and indelible character.

On the five-disc Fragments — one of several versions, among them a 10-LP set — the original album has been both remixed and reimagined; there's a lo-fi live disc; one containing relevant, previously released tunes; and two discs of completely unreleased (and astonishing) process-oriented material that capture the evolution of Time Out of Mind's songs with fascinating, jettisoned lyrics and arrangements that anyone else would've been thrilled with. In terms of stuff that was attempted but left behind for later (or abandoned for good), everything here is startling.

Dylan began these sessions covering "The Water Is Wide," ostensibly to get him warm and in the mood to reveal new songs — this traditional conjures the kind of endless travel that Time Out of Mind would explore, with lyrics like "Love is gentle, love is kind / The sweetest flower when first it's new / But love grows old and waxes cold / And fades away like morning dew," setting the resigned, fatalistic table that Dylan's notebooks of words likely rested on.

"Dreamin' of You" is an early exploration for Dylan, as he pondered re-teaming with Lanois for the first time since their triumphant 1989 album, Oh Mercy. It contains a hodgepodge of lyrics Dylan would eventually include on songs like "Standing in the Doorway" or else scrap, but it's a powerfully loose document of how much magic Dylan has at his command.

"Red River Shore" is a lost original from these sessions, and unlike a previously released version that's arranged as a poignant ballad (and can be heard on the final Fragments disc, comprised of material we first heard on Tell Tale Signs: The Bootleg Series Vol. 8), version one here is locked in a groove, with Dylan delivering more of a downcast, Bruce Springsteen-via-Woody Guthrie reading of the remarkable song. In a second attempt, it lands as a lovely epic full of ache and longing, with Dylan embracing its beautiful melody and structure. Though he seemingly never attempted it again for a subsequent album, it vaguely forecasts the repetition-steeped epics that would appear on Modern Times and Tempest.

"Mississippi" is simply one of Dylan's most perfect songs, appearing here four different times (not including a live version); the lyrics and vocals are as solidly sculpted as they appear on 2001's "Love and Theft." Clashes with Lanois over the merits of "Mississippi" meant it wouldn't make Time Out of Mind, but at least two of the arrangements here are so beautiful, I'd be happy hearing a million more.

The disc of live performances included in this set are generally so raw, if you closed your eyes you'd think you were actually in the bleachers, sitting beside a taper. There's an arrangement of "Can't Wait" from a Nashville show in 1999 that rips so hard, you'd want to rush the stage (props to Dylan's longest-serving collaborator, bassist Tony Garnier, who came up with a memorable part), while the improved fidelity of "'Til I Fell in Love with You," recorded in Buenos Aires in 1998, is a surprising and welcome blast.

In terms of Time Out of Mind, the new mixes are revelatory, getting us closer to Dylan's voice than the original album enabled us to. Much of the processing and distortion that Lanois and Howard fashioned for the songs has been tempered or removed, and Dylan's singing suddenly sounds unburied, soaring higher here (though, according to Howard, it was Dylan himself who revelled in the kind of Sun Records/Bullet mic murk that the engineer helped him achieve at the time).

Instrumentation is also levelled differently, faders removing, adding or adapting the familiar foundational feel and flourishes fans have grown accustomed to. Or at least it seems that way; much like a great Dylan song, some of these remixes may make you feel like you're hearing strange things or make you question what you heard in the first place.

Take "Make You Feel My Love" — now an American standard and one of Dylan's most impactful ballads (made most famous by Adele), "Make You Feel My Love" is more or less a new song here, with a much cleaner vocal, subtle drums that were never present on Time Out of Mind, and a bassless final bridge that leaves just the piano, a faint organ and Dylan's voice to drive the emotion home unfettered. It's a simple decision that poignantly changes the tenor of the song, making its gallant promises all the more direct.

There are more than a few such surprises laying in wait on the remixed album proper, where canon arrangements are tweaked just so, often to profound effect. Time Out of Mind is eerily, hauntingly matter-of-fact in its substance, as Dylan sings of persevering and roaming Earth's painful corners. These corners are occupied by many ghosts — departed friends, lost lovers, any sense of humanity itself gone down the drain — and putting the record on has long conjured a few different visions of afterlife.

In their respective liner notes for Fragments, Douglas Brinkley and Steven Hyden each delve into the history and making of Time Out of Mind, which went on to win the Grammy for Album of the Year and, depending on your perspective of his standing, assuredly launched the sixth or 60th Bob Dylan Renaissance. Whichever one it was, it's the one he's still basking and flourishing in (Hyden alludes to the Jokermen podcast to suggest that, for some other generation, 2020's Rough and Rowdy Ways is also Dylan's greatest album).

Dylan himself had cited the passing of his friend and hero, Grateful Dead figurehead Jerry Garcia, as one impetus to delve into lyrics about mortality, dread and the loss of close connection. But another tragic figure looms large in the legend of Time Out of Mind's cross-generational resonance: Kurt Cobain.

Cobain was labelled a screamer, but that always seemed like a dismissal of his emotional power and musicality; goddamn, could that guy locate and hold a note. Cobain and Dylan, both children of Lead Belly, mastering tuneful rage and anguish like nobody else — as Dylan sings on "Not Dark Yet," "Behind every beautiful thing, there's been some kind of pain." On Time Out of Mind, you hear Dylan digging deep into his being to pull out his poetry — it's unearthly, the power that his voice pulls from, and it's a wide-ranging, gorgeous instrument that most mortals could never generate. In 1997, many more music fans than usual were seeking such voices out and appreciatively grappling with their genuine force.

A whole lot of us embraced the Nirvana-led boom of underground music and culture as teens, at least partly because it led us to revel in edginess and find beauty in things that had conventionally been categorized as dark, rough and of marginal significance. We learned to laugh in the face of smug, domineering confidence and embrace those who exhibited sensitive curiosity, a generosity of spirit, and even insecure modesty. You don't know? That's okay. I don't know either.

What was at the cultural heart of the 1990s if it wasn't a re-evaluation of all of the bullshit we'd been given in music and film and television, and an elevation of everything that truly questioned and challenged the status quo and what gatekeepers deemed worthwhile or not?

Indeed, before Cobain motioned us forward through those gates, Bob Dylan was already there, often in a corner on his own, accepted and lauded but too uncompromising, idiosyncratic and enigmatically honest for the mainstream to truly exploit. And yet, beyond Nirvana and its ilk gaining credit for obliterating the vapid pretense and phoniness of hair metal and pop stars, their ascendance at least coincided with established Rock Hall artists (Neil Young, Tom Waits, Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, Madonna, U2, R.E.M., et al.) realizing that their grittier, more experimental impulses could not only be explored, they may well be rewarded.

Is it a coincidence that the very first edition of Dylan's hugely influential, humanizing, warts-and-all Bootleg Series was released on March 26, 1991 — "the year punk broke," and changed…well, everything? I don't think it's an accident that in the weird hangover after the likes of Ice-T, the Jesus Lizard, Quentin Tarantino and Seinfeld rose and fell in influence and prominence in the late '90s — each with their own kind of pleasant profanity, disaffection, and questioning cynicism — Dylan truly emerged as a unifying figure.

On March 25, 2001, almost exactly 10 years to the day after the Bootleg Series first began, Dylan accepted an Oscar for "Things Have Changed" from Curtis Hanson's Wonder Boys; in his acceptance speech, he thanked "the members of the Academy who were bold enough to give me this award for this song, which obviously is a song that doesn't pussyfoot around, nor turn a blind eye to human nature." He could've been talking about any one of his own songs, or any of the best ones to break through and bother perplexed media executives in the previous decade; "I used to care, but things have changed," sounded like Dylan speaking on behalf of the Lollapalooza generation in his rearview, and it got our attention.

Once they got past the clichés about Dylan, the creative worlds of the evolving 1990s — punk, post-hardcore, underground noise, free jazz, blues, indie-rock fans and musicians, rebellious filmmakers, comedians, writers — opened to his work. Nearly everything that was questioning, sophisticated, outspoken, hopeful, challenging, romantic, angry and freeing about those subcultures was conveyed in not just Dylan's lyricism and music — it was all right there, in the powerful roar of his time-worn voice.

In a heady time for outsider art, one of its leading proponents re-established himself at the perfect time, armed with an adventurous artistic spirit that for him at least, meant a song was never really done or definable. There's freedom in the unfinished, and Dylan found some of it in crafting Time Out of Mind, indisputably one of, if not the, greatest album he's made yet.

(Columbia)It's a scorching outtake, with Dylan biting into his cinematic verses, many of which he'd eventually alter, as the band blends a perfect amalgam of heft and space for a menacing "Ballad of a Thin Man" bounce. It starts innocently and evenly before the full spectrum of sound kicks in and Dylan launches into the vocal like a tiger, but then he doubts himself.

"I don't know." Really?

It's such a specifically certain circumstance to be unsure about, but then, counting a couple of live variations, there are five unique versions of "Can't Wait" on Fragments, the 17th volume of Dylan's generous Bootleg Series, which captures the sessions for 1997's Time Out of Mind, Dylan's 30th (and, to a certain generation of fans, best) album.

As such, this indispensable and revelatory treatment is as loving and comprehensive as can be, giving us a sense of how Dylan and his various collaborators nailed down these spooky, funny, hard songs pondering loneliness, independence and the end of one's days. Beyond the stellar players, Dylan's accomplices notably include producer Daniel Lanois and engineer Mark Howard, a Canadian tandem who helped Dylan give these wondrous songs their ambience and indelible character.

On the five-disc Fragments — one of several versions, among them a 10-LP set — the original album has been both remixed and reimagined; there's a lo-fi live disc; one containing relevant, previously released tunes; and two discs of completely unreleased (and astonishing) process-oriented material that capture the evolution of Time Out of Mind's songs with fascinating, jettisoned lyrics and arrangements that anyone else would've been thrilled with. In terms of stuff that was attempted but left behind for later (or abandoned for good), everything here is startling.

Dylan began these sessions covering "The Water Is Wide," ostensibly to get him warm and in the mood to reveal new songs — this traditional conjures the kind of endless travel that Time Out of Mind would explore, with lyrics like "Love is gentle, love is kind / The sweetest flower when first it's new / But love grows old and waxes cold / And fades away like morning dew," setting the resigned, fatalistic table that Dylan's notebooks of words likely rested on.

"Dreamin' of You" is an early exploration for Dylan, as he pondered re-teaming with Lanois for the first time since their triumphant 1989 album, Oh Mercy. It contains a hodgepodge of lyrics Dylan would eventually include on songs like "Standing in the Doorway" or else scrap, but it's a powerfully loose document of how much magic Dylan has at his command.

"Red River Shore" is a lost original from these sessions, and unlike a previously released version that's arranged as a poignant ballad (and can be heard on the final Fragments disc, comprised of material we first heard on Tell Tale Signs: The Bootleg Series Vol. 8), version one here is locked in a groove, with Dylan delivering more of a downcast, Bruce Springsteen-via-Woody Guthrie reading of the remarkable song. In a second attempt, it lands as a lovely epic full of ache and longing, with Dylan embracing its beautiful melody and structure. Though he seemingly never attempted it again for a subsequent album, it vaguely forecasts the repetition-steeped epics that would appear on Modern Times and Tempest.

"Mississippi" is simply one of Dylan's most perfect songs, appearing here four different times (not including a live version); the lyrics and vocals are as solidly sculpted as they appear on 2001's "Love and Theft." Clashes with Lanois over the merits of "Mississippi" meant it wouldn't make Time Out of Mind, but at least two of the arrangements here are so beautiful, I'd be happy hearing a million more.

The disc of live performances included in this set are generally so raw, if you closed your eyes you'd think you were actually in the bleachers, sitting beside a taper. There's an arrangement of "Can't Wait" from a Nashville show in 1999 that rips so hard, you'd want to rush the stage (props to Dylan's longest-serving collaborator, bassist Tony Garnier, who came up with a memorable part), while the improved fidelity of "'Til I Fell in Love with You," recorded in Buenos Aires in 1998, is a surprising and welcome blast.

In terms of Time Out of Mind, the new mixes are revelatory, getting us closer to Dylan's voice than the original album enabled us to. Much of the processing and distortion that Lanois and Howard fashioned for the songs has been tempered or removed, and Dylan's singing suddenly sounds unburied, soaring higher here (though, according to Howard, it was Dylan himself who revelled in the kind of Sun Records/Bullet mic murk that the engineer helped him achieve at the time).

Instrumentation is also levelled differently, faders removing, adding or adapting the familiar foundational feel and flourishes fans have grown accustomed to. Or at least it seems that way; much like a great Dylan song, some of these remixes may make you feel like you're hearing strange things or make you question what you heard in the first place.

Take "Make You Feel My Love" — now an American standard and one of Dylan's most impactful ballads (made most famous by Adele), "Make You Feel My Love" is more or less a new song here, with a much cleaner vocal, subtle drums that were never present on Time Out of Mind, and a bassless final bridge that leaves just the piano, a faint organ and Dylan's voice to drive the emotion home unfettered. It's a simple decision that poignantly changes the tenor of the song, making its gallant promises all the more direct.

There are more than a few such surprises laying in wait on the remixed album proper, where canon arrangements are tweaked just so, often to profound effect. Time Out of Mind is eerily, hauntingly matter-of-fact in its substance, as Dylan sings of persevering and roaming Earth's painful corners. These corners are occupied by many ghosts — departed friends, lost lovers, any sense of humanity itself gone down the drain — and putting the record on has long conjured a few different visions of afterlife.

In their respective liner notes for Fragments, Douglas Brinkley and Steven Hyden each delve into the history and making of Time Out of Mind, which went on to win the Grammy for Album of the Year and, depending on your perspective of his standing, assuredly launched the sixth or 60th Bob Dylan Renaissance. Whichever one it was, it's the one he's still basking and flourishing in (Hyden alludes to the Jokermen podcast to suggest that, for some other generation, 2020's Rough and Rowdy Ways is also Dylan's greatest album).

Dylan himself had cited the passing of his friend and hero, Grateful Dead figurehead Jerry Garcia, as one impetus to delve into lyrics about mortality, dread and the loss of close connection. But another tragic figure looms large in the legend of Time Out of Mind's cross-generational resonance: Kurt Cobain.

Cobain was labelled a screamer, but that always seemed like a dismissal of his emotional power and musicality; goddamn, could that guy locate and hold a note. Cobain and Dylan, both children of Lead Belly, mastering tuneful rage and anguish like nobody else — as Dylan sings on "Not Dark Yet," "Behind every beautiful thing, there's been some kind of pain." On Time Out of Mind, you hear Dylan digging deep into his being to pull out his poetry — it's unearthly, the power that his voice pulls from, and it's a wide-ranging, gorgeous instrument that most mortals could never generate. In 1997, many more music fans than usual were seeking such voices out and appreciatively grappling with their genuine force.

A whole lot of us embraced the Nirvana-led boom of underground music and culture as teens, at least partly because it led us to revel in edginess and find beauty in things that had conventionally been categorized as dark, rough and of marginal significance. We learned to laugh in the face of smug, domineering confidence and embrace those who exhibited sensitive curiosity, a generosity of spirit, and even insecure modesty. You don't know? That's okay. I don't know either.

What was at the cultural heart of the 1990s if it wasn't a re-evaluation of all of the bullshit we'd been given in music and film and television, and an elevation of everything that truly questioned and challenged the status quo and what gatekeepers deemed worthwhile or not?

Indeed, before Cobain motioned us forward through those gates, Bob Dylan was already there, often in a corner on his own, accepted and lauded but too uncompromising, idiosyncratic and enigmatically honest for the mainstream to truly exploit. And yet, beyond Nirvana and its ilk gaining credit for obliterating the vapid pretense and phoniness of hair metal and pop stars, their ascendance at least coincided with established Rock Hall artists (Neil Young, Tom Waits, Michael Jackson, Bruce Springsteen, Madonna, U2, R.E.M., et al.) realizing that their grittier, more experimental impulses could not only be explored, they may well be rewarded.

Is it a coincidence that the very first edition of Dylan's hugely influential, humanizing, warts-and-all Bootleg Series was released on March 26, 1991 — "the year punk broke," and changed…well, everything? I don't think it's an accident that in the weird hangover after the likes of Ice-T, the Jesus Lizard, Quentin Tarantino and Seinfeld rose and fell in influence and prominence in the late '90s — each with their own kind of pleasant profanity, disaffection, and questioning cynicism — Dylan truly emerged as a unifying figure.

On March 25, 2001, almost exactly 10 years to the day after the Bootleg Series first began, Dylan accepted an Oscar for "Things Have Changed" from Curtis Hanson's Wonder Boys; in his acceptance speech, he thanked "the members of the Academy who were bold enough to give me this award for this song, which obviously is a song that doesn't pussyfoot around, nor turn a blind eye to human nature." He could've been talking about any one of his own songs, or any of the best ones to break through and bother perplexed media executives in the previous decade; "I used to care, but things have changed," sounded like Dylan speaking on behalf of the Lollapalooza generation in his rearview, and it got our attention.

Once they got past the clichés about Dylan, the creative worlds of the evolving 1990s — punk, post-hardcore, underground noise, free jazz, blues, indie-rock fans and musicians, rebellious filmmakers, comedians, writers — opened to his work. Nearly everything that was questioning, sophisticated, outspoken, hopeful, challenging, romantic, angry and freeing about those subcultures was conveyed in not just Dylan's lyricism and music — it was all right there, in the powerful roar of his time-worn voice.

In a heady time for outsider art, one of its leading proponents re-established himself at the perfect time, armed with an adventurous artistic spirit that for him at least, meant a song was never really done or definable. There's freedom in the unfinished, and Dylan found some of it in crafting Time Out of Mind, indisputably one of, if not the, greatest album he's made yet.