It's difficult to imagine what a world without Brian Eno would sound like.

An art school graduate and self-described "non-musician," Eno conceptualized a new approach to music through dedicated use of tape loops and sampling, smuggling ideas previously offered by the avant-garde into the pop/rock lexicon as a founding member of Roxy Music and early collaborations with King Crimson's Robert Fripp, eventually breaking free to codify the ambient music genre and presage music created by algorithms and apps with generative music. Along the way, he inspired pioneers like the Bomb Squad and the Orb, and produced important albums for the likes of David Bowie, Devo, the Talking Heads and U2.

Production credits aside, he's responsible for some 60 solo and collaborative releases, and though charting that legendary output can often feel disorienting, many of his early creations sound as fresh today as when they first debuted — and recent works sound just as timeless, yielding new experiences upon each repeat listen, by design. So as Eno continues to revisit his early works with an expanded edition of his 1983 Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks album, today we're breaking down his prolific career with a guide to the essential Brian Eno albums.

Essential Albums:

10. Brian Eno

Reflection

(2017)

Eno laid so much foundation in the years following his term in Roxy Music, it's easy to get caught up in the albums he released in the '70s and '80s — especially since software-based generative works caused fan interest to cool significantly in the early '90s. But this 2017 generative work comes full circle as Eno returns to the ambient form with an album that bears more familiarity with drone than the soft touches of Music For Airports.

While the album proper offers a static representation of the contemplative programming, in theory it stretches into infinity via an iOS app users can experience live, making it the most accessible of Eno's installation works and a career highlight, quintessentially timeless and without place.

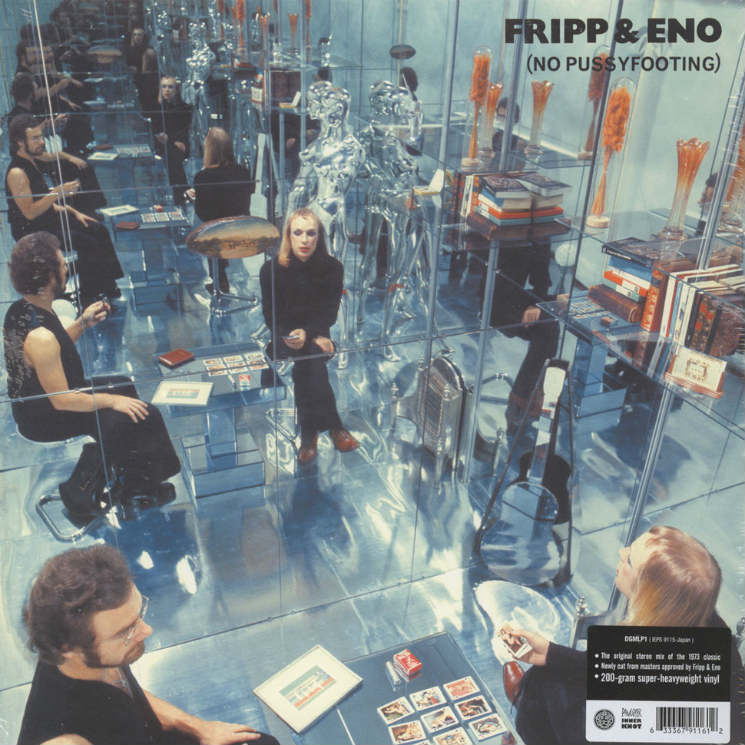

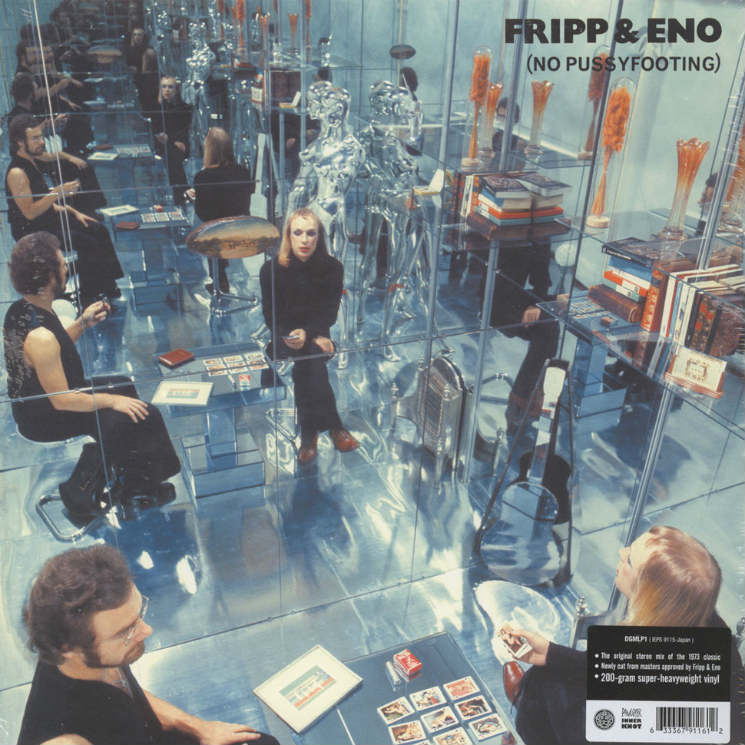

9. Fripp & Eno

(No Pussyfooting)

(1973)

The outcome of Eno and Robert Fripp's early adventures in Eno's London home studio, 1973's (No Pussyfooting) anticipates much of everything Eno was about to do. Still yet to depart Roxy Music, he and Fripp recorded the album in just three days between September 1972 and August 1973, but the proto-ambient explorations they set down represent a radical reinvention of their respective styles, looping a pair of reel-to-reel tape recorders to create what later became known as "Frippertronics" — Eno experimenting with live tape manipulations.

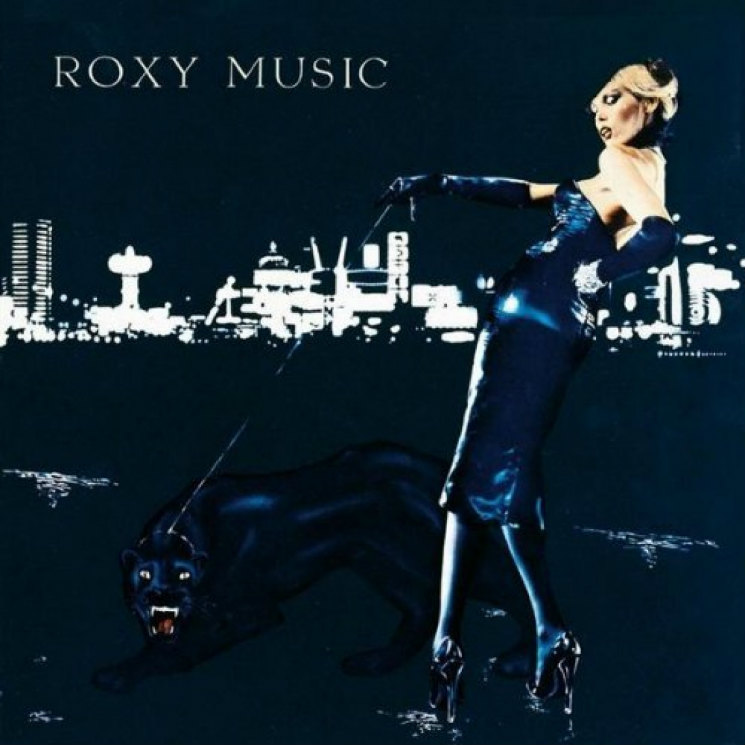

8. Roxy Music

For Your Pleasure

(1973)

Though fronted by founder Bryan Ferry, for a brief time in his salad days with Roxy Music a glammed-up Eno absorbed a leopard-printed lion's share of the celebrity by providing synthesizers and "treatments" for the band, igniting a rivalry that ultimately provoked him to break away entirely.

He was destined for greater things, but his time in Roxy Music shouldn't be missed, as it planted seeds for future collaborative relationships and provided important context for the artistic foundation from which he burst. Displaying early efforts to smuggle Reichian phasing effects and minimalism into pop music via synthesizer and tape experiments, his second and final record with the band is especially worthy of attention.

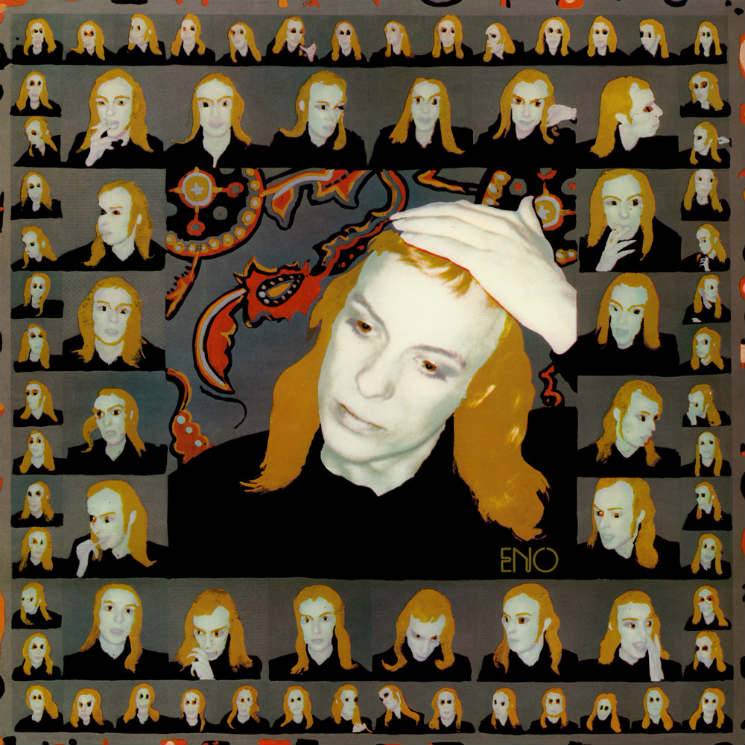

7. Brian Eno

Here Come the Warm Jets

(1974)

His solo debut, Eno wrote Here Come the Warm Jets in a feverish frenzy after leaving Roxy Music ("Baby's on Fire" was reportedly written the very day he left the band). Contracting 16 guests — including Robert Fripp and all the members of Roxy Music except for Bryan Ferry — it's a bizarro parallel of Ferry's project that had Eno conducting the action through a series of unconscious gestures, often directing his guests' playing through dance and generating nonsensical scratch vocals he'd later assign "proper" words to.

6. Brian Eno

Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)

(1974)

After the glammy exercise in psychic telegraphing that was Here Come the Warm Jets, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) systematized Eno's experiments in consciousness, developing his infamous Oblique Strategies cards with friend Peter Schmidt and allowing their aphorisms to instruct the creative process. Taking additional inspiration from a group of postcards of the Chinese Cultural Revolution's "model operas," it also signals an early interest in evoking landscapes.

5. Brian Eno-David Byrne

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts

(1981)

By the late '70s, Eno had distanced himself from music that prioritized lyrical meaning and explicitly discounted the importance of lyrics.

Having produced Talking Heads albums More Songs About Buildings and Food and Fear of Music, he and David Byrne developed a friendship and began exploring releases on Ocora, a French label specializing in field recordings of non-Western music. After briefly pursuing an album with Jon Hassell — who was at the time beginning to build out his "Fourth World" concept — the pair set to work developing an album of field recordings documenting the music of an imaginary country.

Setting tape loops of found vocals against rhythm tracks, the pair assembled playing familiar instruments in unfamiliar ways. Recording was a process of trial and error, the resulting transcultural pastiche a product of extensive, radical sampling, serendipity and curation, that captured Eno and Byrne one step ahead of the postmodern zeitgeist.

4. Brian Eno

Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks

(1983)

Although Eno's catalogue has generally gravitated toward articulating earthly landscapes, on his last major musical work he set the controls for the new frontier of outer space, partnering with Ambient 4: On Land engineer Daniel Lanois and his brother Roger Eno for a soundtrack to Al Reinert's documentary about NASA's Apollo program, For All Mankind. Appropriately incorporating Lanois' pedal steel, it took off into darker ambient sound territory, celestial drifts navigating the untethered stillness of distant heavenly bodies. It also announced a creative partnership that would help U2 usher in some of their greatest works; Eno and Lanois later applied their stratospheric touch to the production of The Unforgettable Fire, Achtung Baby and The Joshua Tree.

3. Brian Eno

Discreet Music

(1975)

In a formative twist of fate, in 1975, Eno was returning home from a recording session when, crossing a road, he was struck by a cab and hospitalized. Confined to a bed for weeks, his friend Judy Nylon dropped by with an album of 18th Century harp music, and after she left, Eno set it up on the stereo, only to return to bed to find the amplifier set "extremely low." Too weak to adjust the volume, he was forced to absorb it as part of his immediate environment — the perceptible sounds of the stereo immersed in the ambience of the rain on the window. For Eno, it was a new way of listening to music.

A stylistic departure from his earlier rock-influenced records, Discreet Music was directly inspired by the experience, the synth and tape-loop generated title track sending listeners on a gentle half-hour drift intended for play over exceptionally low volumes, while the remaining pieces strip Pachelbel's "Canon in D Major" of its functional harmonics by overlaying parts in ways not intended by the original score, thereby blurring and undermining progressions.

Analogue prototypes for a career interest in generative music and his first entries into what he would later dub ambient music, the ideas he explored here changed his approach to music forever, though he'd soon after dovetail them with others he'd previously explored, precipitating his most defining works.

2. Brian Eno

Another Green World

(1975)

Recorded after Discreet Music but released first, what makes Another Green World exceptional is the glimpse it offers into a pivotal period in Eno's early solo career.

Bringing together guest contributions from Robert Fripp, John Cale, Phil Collins and Hawkwind Lemmy replacement Paul Rudolph, the album credits read like the program for some rock royalty summit, but musicians frequently didn't see each other when recording, passing like ships in the night as Eno solicited takes and assembled tracks with no demos in mind, instead referencing a deck of Oblique Strategy Cards.

It's often lumped amongst Eno's "song records," but it bears more similarity to the ambient music he would later pursue. The instrumental entries outnumber the five with lyrics, and those that do contain words argue against their own importance. And there are no big finishes or announcements, either — tracks fade in and out like scenes Eno happened upon in the field (and, in some cases, would later return to: differently mixed instrumentation from "Sky Saw" features on Music for Films and the debut Ultravox album Eno oversaw, while "Zawinul/Lava" provides a version of a piano figure that features prominently in Music for Airports), foreshadowing a production technique that would inform his work on Bowie's Low and U2's The Joshua Tree.

1. Brian Eno

Ambient 1: Music for Airports

(1978)

Discreet Music was arguably Eno's first concentrated exploration of ambient music, but with Ambient 1: Music for Airports, he gave it a name and codified the form, issuing a mission statement in the liner notes: "Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting."

Originally conceived as a counter to the environment-cluttering muzak he endured during an extended wait at Cologne Bonn Airport, it's an inspired work of immersive, stimulated calm that phases tape loops of piano, synthesizer and vocal performances to serene effect, their theoretically endless pattern evolutions emanating perfume-y atmospheres that allow you to adjust your attention to it or your surroundings with becalmed ease and reward.

Timeless and placeless, it's a glistening crystallization of some of the most important concepts that have inspired his catalogue — ambient music, cybernetics, generative music, imaginary landscapes — and a landmark recording that places him along a continuum of avant-garde legends like John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Erik Satie and La Monte Young. Remaining his bestselling work to this day, it's Eno's crowning achievement and the perfect introduction to the vast constellation of work he's produced over the past 50 years.

What to Avoid:

Eno went to art school. It makes sense that in time, he'd tire of his familiar devices and move on to something new. In the '90s, this yielded some results that prove exceedingly frustrating for contemporary fans, as Eno's fascination with generative music led him to pursue a series of albums released exclusively on media that's become obsolete.

Headcandy (1994) is almost impossible to track down, and the first CD is a data track made exclusively for Windows 3.1. Similarly, Generative Music 1 (1996) is only available on a floppy disk. Produced using a Koan Pro software synthesizer from Sseyo, every track plays differently each time you play it, so even if you can track it down, there's no guarantee what you'll get out of it.

Others were pale retrospectives of moments that came and went. A reinterpretation of his lost album My Squelchy Life, Nerve Net (1992) listens like a stale presentation of era synthesizer presets, beatnik rap and guest-contributed spoken word, including a vocoder rape story ("What Actually Happened") that time hasn't done any favours. Recorded between 1985 and 1990, The Shutov Assembly (1992) adds up to little more than a disconnected collection of previously unreleased ambient material Eno slapped together for Russian painter friend Sergei Shutov made public. The hour-long, single track album Neroli (1993) offered an extended look at a piece for which a four-minute edit already existed (see "Constant Dreams" on 1989's Textures); but despite Eno's stated intention for the track "to reward attention, but not so strict as to demand it," its directionless pings quickly fail his own ignorable/interesting test. As for The Drop (1997, pictured above)? Well, let's just say Eno's original title for this collection of dusky impressionistic instrumentals was Unwelcome Jazz and leave it at that.

Otherwise, listeners should be advised that not all of Eno's collaborative releases have been as fruitful as (No Pussyfooting) or My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Convening with U2 after the sessions that produced their oddball Zooropa album, Eno proposed the band do some improvising sessions and the group eventually turned their attention to creating soundtracks for imaginary films à la Eno's Music for Films (1978), incorporating Eno as a songwriting partner under the collective pseudonym Passengers. The resulting Original Soundtracks 1 (1995), is a mainly instrumental volume that represents U2 at its most abstract, but it's also plagued by Bono mumbling absurd lyrical fragments like "Don't want to be a slug / Don't want to overdress."

Later, Drawn from Life (2001), Eno's collaboration with German composer/DJ J. Peter Schwalm, felt like deflated trip-hop, and Drums Between the Bells and the subsequent Panic of Looking EP, Eno's 2011 works with spoken word artist Rick Holland, are an uneven collection of sound worlds, the latter reading as little more than publicity for Eno's Moogfest residency — especially since its 16 minutes put more emphasis on Holland's words. More recently, Someday World (2014), the first result of an attempt to bring the minimalism of Steve Reich or Philip Glass into the realm of Afrobeat with Underworld's Karl Hyde, sounds like exactly what it is: a hard-drive dump of incomplete ideas cut-and-pasted together. It's cold and clunky.

Further Listening:

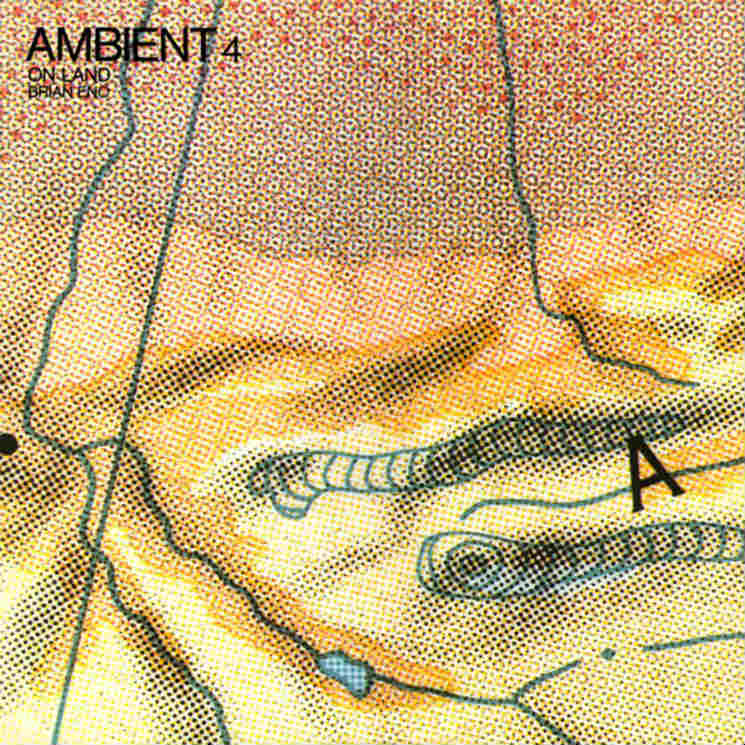

Where you should turn next depends largely on who your Eno is. For fans of ambient Eno, the remaining entries in his ambient series are the obvious next step. Work your way through the series chronologically and start with Eno cushioning Harold Budd's soft piano touches on Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror (1980), or skip right ahead to Ambient 4: On Land (1982, pictured above); arguably even better than Eno's seminal first entry, his ambient atmospheres incorporate a newfound density here. (Ambient 3, it bears mentioning, is a record by Laraaji, only produced by Eno.) Another Harold Budd encounter, The Pearl (1984), introduced more pronounced electronic treatments, and included additional help from Daniel Lanois.

As if it was only a matter of time, Eno's ambient practice eventually found appropriate application in art installation contexts. The best opportunity to get familiar with this area of his practice is the compilation Music for Installations (2018), gathering works reaching as far back as 1985, but Lux (2012) is another highlight that simultaneously reiterates Discreet Music's message while pointing it in a new direction.

Music for Films (1978), its 1983 sequel, and Small Craft on a Milk Sea (2010) fill the conceptual gap between Eno's ambient works and environmental set dressers like Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, while Thursday Afternoon (1985) adds a new dimension to these pursuits with a series of "video paintings."

Meanwhile, Evening Star (1975) and The Equatorial Stars (2004) find Eno and Fripp picking up where they left off on their proto-ambient debut.

Despite shifting focus away from the pop format after launching his ambient manifesto, there is plenty left in Eno's catalogue for fans of his "song" records. Before and After Science (1977) is practically essential, as it finds Eno navigating his transitional period between art-indebted pop and unfiltered Art, while The Ship (2016) provides lyricism that becomes a part of the landscape. In between, he made two exceptional records with longtime collaborators — Wrong Way Up (1990) and Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (2008). While the former had Eno and John Cale squaring off to glorious effect, the latter found Eno and David Byrne following up their first collaboration with drastically different "electronic gospel."

For Bush of Ghosts fans, Fourth World, Vol. 1: Possible Musics (1980) is an adjacent classic. Though truly more of a Jon Hassell project, it's practically the sibling record to Eno and Byrne's first undertaking, smearing non-Western musics together with Hassell's experimental trumpet technique and tape loop experiments. Together, these two records provide a foundation for exciting future undertakings like Spinner (1995), which found Eno putting treatments on Jah Wobble's brushed drum dubscapes, and Highlife (2014), a reunion with Karl Hyde that vastly improves on Someday World.

And of course, if you fancy his work in Roxy Music, go back to where everything began, throw on their eponymous 1972 debut and work your way through their discography, tracking Eno's influence beyond his departure following For Your Pleasure.

An art school graduate and self-described "non-musician," Eno conceptualized a new approach to music through dedicated use of tape loops and sampling, smuggling ideas previously offered by the avant-garde into the pop/rock lexicon as a founding member of Roxy Music and early collaborations with King Crimson's Robert Fripp, eventually breaking free to codify the ambient music genre and presage music created by algorithms and apps with generative music. Along the way, he inspired pioneers like the Bomb Squad and the Orb, and produced important albums for the likes of David Bowie, Devo, the Talking Heads and U2.

Production credits aside, he's responsible for some 60 solo and collaborative releases, and though charting that legendary output can often feel disorienting, many of his early creations sound as fresh today as when they first debuted — and recent works sound just as timeless, yielding new experiences upon each repeat listen, by design. So as Eno continues to revisit his early works with an expanded edition of his 1983 Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks album, today we're breaking down his prolific career with a guide to the essential Brian Eno albums.

Essential Albums:

10. Brian Eno

Reflection

(2017)

Eno laid so much foundation in the years following his term in Roxy Music, it's easy to get caught up in the albums he released in the '70s and '80s — especially since software-based generative works caused fan interest to cool significantly in the early '90s. But this 2017 generative work comes full circle as Eno returns to the ambient form with an album that bears more familiarity with drone than the soft touches of Music For Airports.

While the album proper offers a static representation of the contemplative programming, in theory it stretches into infinity via an iOS app users can experience live, making it the most accessible of Eno's installation works and a career highlight, quintessentially timeless and without place.

9. Fripp & Eno

(No Pussyfooting)

(1973)

The outcome of Eno and Robert Fripp's early adventures in Eno's London home studio, 1973's (No Pussyfooting) anticipates much of everything Eno was about to do. Still yet to depart Roxy Music, he and Fripp recorded the album in just three days between September 1972 and August 1973, but the proto-ambient explorations they set down represent a radical reinvention of their respective styles, looping a pair of reel-to-reel tape recorders to create what later became known as "Frippertronics" — Eno experimenting with live tape manipulations.

8. Roxy Music

For Your Pleasure

(1973)

Though fronted by founder Bryan Ferry, for a brief time in his salad days with Roxy Music a glammed-up Eno absorbed a leopard-printed lion's share of the celebrity by providing synthesizers and "treatments" for the band, igniting a rivalry that ultimately provoked him to break away entirely.

He was destined for greater things, but his time in Roxy Music shouldn't be missed, as it planted seeds for future collaborative relationships and provided important context for the artistic foundation from which he burst. Displaying early efforts to smuggle Reichian phasing effects and minimalism into pop music via synthesizer and tape experiments, his second and final record with the band is especially worthy of attention.

7. Brian Eno

Here Come the Warm Jets

(1974)

His solo debut, Eno wrote Here Come the Warm Jets in a feverish frenzy after leaving Roxy Music ("Baby's on Fire" was reportedly written the very day he left the band). Contracting 16 guests — including Robert Fripp and all the members of Roxy Music except for Bryan Ferry — it's a bizarro parallel of Ferry's project that had Eno conducting the action through a series of unconscious gestures, often directing his guests' playing through dance and generating nonsensical scratch vocals he'd later assign "proper" words to.

6. Brian Eno

Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy)

(1974)

After the glammy exercise in psychic telegraphing that was Here Come the Warm Jets, Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) systematized Eno's experiments in consciousness, developing his infamous Oblique Strategies cards with friend Peter Schmidt and allowing their aphorisms to instruct the creative process. Taking additional inspiration from a group of postcards of the Chinese Cultural Revolution's "model operas," it also signals an early interest in evoking landscapes.

5. Brian Eno-David Byrne

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts

(1981)

By the late '70s, Eno had distanced himself from music that prioritized lyrical meaning and explicitly discounted the importance of lyrics.

Having produced Talking Heads albums More Songs About Buildings and Food and Fear of Music, he and David Byrne developed a friendship and began exploring releases on Ocora, a French label specializing in field recordings of non-Western music. After briefly pursuing an album with Jon Hassell — who was at the time beginning to build out his "Fourth World" concept — the pair set to work developing an album of field recordings documenting the music of an imaginary country.

Setting tape loops of found vocals against rhythm tracks, the pair assembled playing familiar instruments in unfamiliar ways. Recording was a process of trial and error, the resulting transcultural pastiche a product of extensive, radical sampling, serendipity and curation, that captured Eno and Byrne one step ahead of the postmodern zeitgeist.

4. Brian Eno

Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks

(1983)

Although Eno's catalogue has generally gravitated toward articulating earthly landscapes, on his last major musical work he set the controls for the new frontier of outer space, partnering with Ambient 4: On Land engineer Daniel Lanois and his brother Roger Eno for a soundtrack to Al Reinert's documentary about NASA's Apollo program, For All Mankind. Appropriately incorporating Lanois' pedal steel, it took off into darker ambient sound territory, celestial drifts navigating the untethered stillness of distant heavenly bodies. It also announced a creative partnership that would help U2 usher in some of their greatest works; Eno and Lanois later applied their stratospheric touch to the production of The Unforgettable Fire, Achtung Baby and The Joshua Tree.

3. Brian Eno

Discreet Music

(1975)

In a formative twist of fate, in 1975, Eno was returning home from a recording session when, crossing a road, he was struck by a cab and hospitalized. Confined to a bed for weeks, his friend Judy Nylon dropped by with an album of 18th Century harp music, and after she left, Eno set it up on the stereo, only to return to bed to find the amplifier set "extremely low." Too weak to adjust the volume, he was forced to absorb it as part of his immediate environment — the perceptible sounds of the stereo immersed in the ambience of the rain on the window. For Eno, it was a new way of listening to music.

A stylistic departure from his earlier rock-influenced records, Discreet Music was directly inspired by the experience, the synth and tape-loop generated title track sending listeners on a gentle half-hour drift intended for play over exceptionally low volumes, while the remaining pieces strip Pachelbel's "Canon in D Major" of its functional harmonics by overlaying parts in ways not intended by the original score, thereby blurring and undermining progressions.

Analogue prototypes for a career interest in generative music and his first entries into what he would later dub ambient music, the ideas he explored here changed his approach to music forever, though he'd soon after dovetail them with others he'd previously explored, precipitating his most defining works.

2. Brian Eno

Another Green World

(1975)

Recorded after Discreet Music but released first, what makes Another Green World exceptional is the glimpse it offers into a pivotal period in Eno's early solo career.

Bringing together guest contributions from Robert Fripp, John Cale, Phil Collins and Hawkwind Lemmy replacement Paul Rudolph, the album credits read like the program for some rock royalty summit, but musicians frequently didn't see each other when recording, passing like ships in the night as Eno solicited takes and assembled tracks with no demos in mind, instead referencing a deck of Oblique Strategy Cards.

It's often lumped amongst Eno's "song records," but it bears more similarity to the ambient music he would later pursue. The instrumental entries outnumber the five with lyrics, and those that do contain words argue against their own importance. And there are no big finishes or announcements, either — tracks fade in and out like scenes Eno happened upon in the field (and, in some cases, would later return to: differently mixed instrumentation from "Sky Saw" features on Music for Films and the debut Ultravox album Eno oversaw, while "Zawinul/Lava" provides a version of a piano figure that features prominently in Music for Airports), foreshadowing a production technique that would inform his work on Bowie's Low and U2's The Joshua Tree.

1. Brian Eno

Ambient 1: Music for Airports

(1978)

Discreet Music was arguably Eno's first concentrated exploration of ambient music, but with Ambient 1: Music for Airports, he gave it a name and codified the form, issuing a mission statement in the liner notes: "Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting."

Originally conceived as a counter to the environment-cluttering muzak he endured during an extended wait at Cologne Bonn Airport, it's an inspired work of immersive, stimulated calm that phases tape loops of piano, synthesizer and vocal performances to serene effect, their theoretically endless pattern evolutions emanating perfume-y atmospheres that allow you to adjust your attention to it or your surroundings with becalmed ease and reward.

Timeless and placeless, it's a glistening crystallization of some of the most important concepts that have inspired his catalogue — ambient music, cybernetics, generative music, imaginary landscapes — and a landmark recording that places him along a continuum of avant-garde legends like John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Erik Satie and La Monte Young. Remaining his bestselling work to this day, it's Eno's crowning achievement and the perfect introduction to the vast constellation of work he's produced over the past 50 years.

What to Avoid:

Eno went to art school. It makes sense that in time, he'd tire of his familiar devices and move on to something new. In the '90s, this yielded some results that prove exceedingly frustrating for contemporary fans, as Eno's fascination with generative music led him to pursue a series of albums released exclusively on media that's become obsolete.

Headcandy (1994) is almost impossible to track down, and the first CD is a data track made exclusively for Windows 3.1. Similarly, Generative Music 1 (1996) is only available on a floppy disk. Produced using a Koan Pro software synthesizer from Sseyo, every track plays differently each time you play it, so even if you can track it down, there's no guarantee what you'll get out of it.

Others were pale retrospectives of moments that came and went. A reinterpretation of his lost album My Squelchy Life, Nerve Net (1992) listens like a stale presentation of era synthesizer presets, beatnik rap and guest-contributed spoken word, including a vocoder rape story ("What Actually Happened") that time hasn't done any favours. Recorded between 1985 and 1990, The Shutov Assembly (1992) adds up to little more than a disconnected collection of previously unreleased ambient material Eno slapped together for Russian painter friend Sergei Shutov made public. The hour-long, single track album Neroli (1993) offered an extended look at a piece for which a four-minute edit already existed (see "Constant Dreams" on 1989's Textures); but despite Eno's stated intention for the track "to reward attention, but not so strict as to demand it," its directionless pings quickly fail his own ignorable/interesting test. As for The Drop (1997, pictured above)? Well, let's just say Eno's original title for this collection of dusky impressionistic instrumentals was Unwelcome Jazz and leave it at that.

Otherwise, listeners should be advised that not all of Eno's collaborative releases have been as fruitful as (No Pussyfooting) or My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Convening with U2 after the sessions that produced their oddball Zooropa album, Eno proposed the band do some improvising sessions and the group eventually turned their attention to creating soundtracks for imaginary films à la Eno's Music for Films (1978), incorporating Eno as a songwriting partner under the collective pseudonym Passengers. The resulting Original Soundtracks 1 (1995), is a mainly instrumental volume that represents U2 at its most abstract, but it's also plagued by Bono mumbling absurd lyrical fragments like "Don't want to be a slug / Don't want to overdress."

Later, Drawn from Life (2001), Eno's collaboration with German composer/DJ J. Peter Schwalm, felt like deflated trip-hop, and Drums Between the Bells and the subsequent Panic of Looking EP, Eno's 2011 works with spoken word artist Rick Holland, are an uneven collection of sound worlds, the latter reading as little more than publicity for Eno's Moogfest residency — especially since its 16 minutes put more emphasis on Holland's words. More recently, Someday World (2014), the first result of an attempt to bring the minimalism of Steve Reich or Philip Glass into the realm of Afrobeat with Underworld's Karl Hyde, sounds like exactly what it is: a hard-drive dump of incomplete ideas cut-and-pasted together. It's cold and clunky.

Further Listening:

Where you should turn next depends largely on who your Eno is. For fans of ambient Eno, the remaining entries in his ambient series are the obvious next step. Work your way through the series chronologically and start with Eno cushioning Harold Budd's soft piano touches on Ambient 2: The Plateaux of Mirror (1980), or skip right ahead to Ambient 4: On Land (1982, pictured above); arguably even better than Eno's seminal first entry, his ambient atmospheres incorporate a newfound density here. (Ambient 3, it bears mentioning, is a record by Laraaji, only produced by Eno.) Another Harold Budd encounter, The Pearl (1984), introduced more pronounced electronic treatments, and included additional help from Daniel Lanois.

As if it was only a matter of time, Eno's ambient practice eventually found appropriate application in art installation contexts. The best opportunity to get familiar with this area of his practice is the compilation Music for Installations (2018), gathering works reaching as far back as 1985, but Lux (2012) is another highlight that simultaneously reiterates Discreet Music's message while pointing it in a new direction.

Music for Films (1978), its 1983 sequel, and Small Craft on a Milk Sea (2010) fill the conceptual gap between Eno's ambient works and environmental set dressers like Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, while Thursday Afternoon (1985) adds a new dimension to these pursuits with a series of "video paintings."

Meanwhile, Evening Star (1975) and The Equatorial Stars (2004) find Eno and Fripp picking up where they left off on their proto-ambient debut.

Despite shifting focus away from the pop format after launching his ambient manifesto, there is plenty left in Eno's catalogue for fans of his "song" records. Before and After Science (1977) is practically essential, as it finds Eno navigating his transitional period between art-indebted pop and unfiltered Art, while The Ship (2016) provides lyricism that becomes a part of the landscape. In between, he made two exceptional records with longtime collaborators — Wrong Way Up (1990) and Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (2008). While the former had Eno and John Cale squaring off to glorious effect, the latter found Eno and David Byrne following up their first collaboration with drastically different "electronic gospel."

For Bush of Ghosts fans, Fourth World, Vol. 1: Possible Musics (1980) is an adjacent classic. Though truly more of a Jon Hassell project, it's practically the sibling record to Eno and Byrne's first undertaking, smearing non-Western musics together with Hassell's experimental trumpet technique and tape loop experiments. Together, these two records provide a foundation for exciting future undertakings like Spinner (1995), which found Eno putting treatments on Jah Wobble's brushed drum dubscapes, and Highlife (2014), a reunion with Karl Hyde that vastly improves on Someday World.

And of course, if you fancy his work in Roxy Music, go back to where everything began, throw on their eponymous 1972 debut and work your way through their discography, tracking Eno's influence beyond his departure following For Your Pleasure.