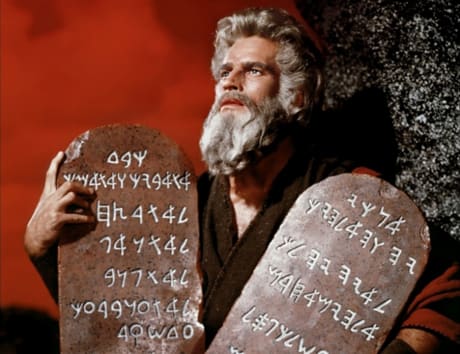

Nobody would confuse the sight of a 33-year-old Charlton Heston in flowing white beard and full Biblical drag pounding his staff on the Pharaoh's marble floor and yelling, "Let my people go!" with neo-realism. Strange, then, that The Ten Commandments opens with Cecil B. DeMille stepping out from behind a curtain to announce that his telling of the life of Moses is based not only upon the Holy Scriptures, but also the works of ancient historians. Is Mister DeMille, that master showman, trying to suggest that his 231-minute, 13-million, 16-ton elephant of a Biblical epic has some pretence of authenticity? One of the most popular films of its day, an Easter TV perennial, a church-basement mainstay and "The greatest event in motion picture history!" (according to its advertising), The Ten Commandments is also routinely dismissed as "Biblical kitsch." The film, it must be said, is not a very convincing evocation of the time and place ― while DeMille and company shot some of the crowd scenes in Egypt, the majority of the indoor and outdoor action takes place on sterile indoor sets; the palaces are spotlessly shiny, with all the engraved pillars looking fresh off the assembly line; the mountainous rocks Moses climbs look like Styrofoam and plastic; and even the peasants' mud pit is perfectly contained. But the movie is so artificial that DeMille is clearly going for something else. Look how he tends toward static medium shots, with two or more actors occupying the same plane, striking the same exaggerated pose for extended periods of time (Bynner with his fists on his hips; Heston with his chest puffed out; Baxter leaning against a wall, looking down in shame). The effect is like a living gothic or medieval painting, where the perspective is flattened, the colours are ripe and the figures strike cartoon poses (the show-stopping climactic orgy sequence at the foot of Mount Sinai looks uncannily like a work by Hieronymus Bosch). Elsewhere, the visual style more closely resembles the Renaissance era: the humble house of Moses's mother has warm, amber lighting too radiant to come exclusively from the few candles. The dialogue is heavy and stilted, with no contractions, as if the actors are reading directly from a questionable translation of the King James Bible where the slaves and the kings talk in the same formal tones. The performances are self-consciously over-the-top: Heston, Yul Brynner (as Rameses), Edward G. Robinson (as Dathan) and Anne Baxter (as Nefretiri), always in breast-enhancing silk, speak in inflated tones, with inflated gestures that suggest a silent film ― and, indeed, DeMille filmed this story once before, in 1923. Certainly Moses is less relatable than the Jesus of revisionist Biblical epics like Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew or Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ, and it's hard to relate to such a flagrantly artificial product on a spiritual level, but somehow that seems beside the point. DeMille combined centuries of religious artistic expression with then state-of-the-art Hollywood histrionics, including the massive set pieces of the second half (the Sinai orgy; the engraving of the Commandments; the parting of a certain Middle Eastern sea), which are so extravagant they grab you like a fire-and-brimstone preacher. The Ten Commandments is more than Biblical kitsch ― it's the synthesis of thousands of years of Biblical kitsch into one outrageous spectacle. It's hard to imagine DeMille's candy-coloured epic looking better than it does in its new DVD and Blu-Ray release, featuring a restoration by Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation. Extras include a Herculean commentary by DeMille expert Katherine Orrison, footage from the 1956 premiere and trailers.

(Paramount Pictures)The Ten Commandments [Blu-Ray]

Cecil B. DeMille

BY Will SloanPublished Mar 25, 2011