Compiling a wealth of incredible photographs from Toronto's underground music scene with the compelling story of growing up amidst the chaos of punk and new wave in the late '70s, Don Pyle's excellent Trouble in the Camera Club: A Photographic Narrative of Toronto's Punk History 1976 - 1980 is a vital piece of Canadian musical history that offers much more than a good coffee table read. "Each time I took a step back and looked at what I was writing, I realized more and more that this has to be about how I came to take these pictures," says former Shadowy Men on a Shadowy Planet drummer Pyle, who began shooting at 14. "I wanted it to be the story of how the pictures came to be, not the story of how the Curse or the Ugly came to be." The result is a deeply personal narrative that rings true with anyone who found solace in music during their teenage years, combined with photos, fliers, and ticket stubs chronically everything from the rise of the Viletones and Teenage Head to legendary appearances by Iggy Pop and Blondie.

Have you had much feedback so far?

Don Pyle: Yeah, actually. All the feedback I've had ― anyone who says anything to my face anyway ― has been overwhelmingly positive. It's been really great, and it's taken me aback. There's been more positive expression than I expected. The last few records I put out have been pretty much totally ignored, so I've gotten used to making something, and no one noticing [laughs].

So this was a little bit of a shift, eh?

Yeah, it has been. And it's easy to feel a bit detached from it because it's taken so long. I think accepting that it was real, and not just in my hands but in other people's hands, as well, has taken me a week or so to get my head around.

For me, what makes it so compelling is that it's so personal. I didn't know what to expect in terms of the writing that would accompany the photos, so beyond the quality of the photos, there's a real sense of magic, that feeling of being a teenager and discovering something. I don't even think you need to have an interest in the specifics of that era of Toronto punk to find it compelling. It's just a great story of being a kid and discovering music.

Thanks, I appreciate that. When I started writing the copy for the book, I easily erased more than I wrote. It took me a long time to find the right tone, the right direction for it. As soon as I started telling any band's story, or describing their history, then I was really aware how I was being dragged in to another book. It was like, "Oh my God, I'm going to write another book! I'm going to write two books! First, the photo book, and now, I have to write the history!" But each time I took a step back and looked at what I was writing, I realized more and more that this has to be about how I came to take these pictures. I wanted it to be the story of how the pictures came to be, not the story of how the Curse or the Ugly came to be. It was really helpful to take that step back. It some ways, I felt like I had to do that to express, as you said, the magic of that time. Thirty-five years later, there's a lot of music that I was really into at that time that I wouldn't necessarily be excited by today. So much of it was that moment. I don't want to read some old guy saying, "This band was great then, but they became crap." There's so much stuff that I love, and I didn't want to be dismissive of where that stuff went, because a lot of people there went to places I didn't find as interesting. But I was thinking a lot about that Sex Pistols... What's the second film? Not The Rock and Roll Swindle?

Oh, The Filth and the Fury.

Yeah, The Filth and the Fury. I found that film so emotional and so moving. And something I thought was so genius about that film was having them in silhouette, so you remain totally in the moment of when this happened. I was thinking about that film, and doing this writing, and trying to remain in that moment, rather than in the present. So I think some of the things I said in the book were kind of silly, or whatever. But they were totally what I was thinking at the time, what I remember thinking then. I think that that's going to convey something more about my feeling taking those pictures, than describing what happened to Teenage Head, or how I feel about their seventh album.

It's a perfect way to frame everything because it's so obviously personal. How many drafts do you think you went through before you came on that particular method?

I don't know if I ever found a method so much as... And I wouldn't even say it was drafts, because it was all over the place. So much writing happens in your head before you put it down on paper. Then you read it later, and you erase 90 percent of it, and start over, thinking, "Oh my God, that's so pretentious. That's boring." It was multiple drafts in multiple sections, and then it was a jigsaw puzzle to pull all this vignettes together to create a narrative flow to the writing. I tried to arrange the photographs in a similar way, so that there was a specific narrative flow to them, not only through time, but the relationship from one band to the next. Like how David Bowie and Bryan Ferry connect to each other, or how the Viletones and the Ugly connect to each other.

To talk a little more about the photos, and I know this is an obvious question, but do you have a favourite photo in the book?

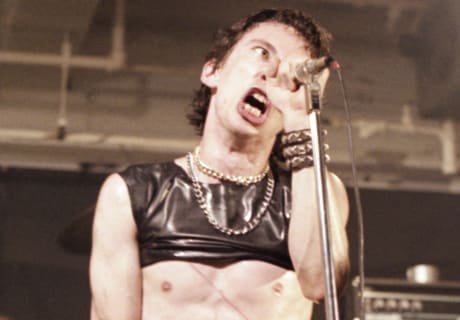

That's something that changes all the time. A couple of people have asked me that, and I had different answers both times. There's one photo right now, a photo of the Viletones at the New Yorker Theatre where [vocalist Steven] Leckie is in the foreground, and he's got a black t-shirt on with the neck and the arms ripped off it. And there's a skull with sunglasses on it, a "Kill 'em all, let God Sort 'em out" kind of thing. He's in the foreground, and Chris Haight is in the background, and he's looking at his bass. He's partially obscured, and there's this really beautiful light coming in from the right side. At different times I fixate on different ones, and go back and look at them, and that's one that's really compelling to me right now. There are a lot of things that I find really interesting about it. One is, there's all this black, open space all around them, but then there's a misty light coming in from the right side that illuminates things and makes the air glow. And Leckie has this dog collar on, and both of them looks really cool. Leckie looks really self-assured and powerful. He looks like a powerful figure on stage, someone who knows that he is in power, and he's here revelling in it. Chris Haight is behind him, and I forget exactly what he's wearing. But there's leather there, he's got his shirt open, there's an iron cross on his guitar strap. Chris Haight is always someone I thought was super cool looking. He's got the real greaser look, that fantastic pompadour. He was always calm, cool, and the quiet guy in the Viletones. So there's a real intensity to his expression there, too. The two of them in that picture are really interesting to me right now.

I love the inclusion of bigger-name people on the same level as the local bands, as part of the same experience. Are you grateful that you had a publisher who didn't insist on more of the famous folks? Did you ever think about not including them at all?

No, I never thought about not including them. When I went through my photographs, I wanted to represent everything I had. There's a picture of Arson that I think is kind of a poor picture. But they were a part of this thing, too. And I wanted them to be a part of this, even if it's just one picture. If I had a picture of any band that was usable, I used it. There were a few things I had that were completely unusable. But if I could include them, they were there. I wish I had so many more photos. Why didn't I take pictures of Sparks opening for Patti Smith? I know the answer, most of the time. I was making $1.30 an hour. Buying film was a significant outlay. So it would be, "Do I buy records, or do I buy film?" A lot of the time, I bought records.

That's pretty fair. It was probably a good idea.

For a lot of the bands there, the idea of "bigger" or "smaller" was less of a concern to me. Locally, everyone started off on the same level. Some of them rose, and years later, we have a totally different perception. Some of them are totally forgotten. Some really great bands have been almost entirely written out of the story by history. It's inevitable. It happens. With Liz Worth's book, Treat Me Like Dirt, that kind of becomes the official history of that time, because it's what people who are 20 years old now can look at and read about. If they read that, they might not know about Drastic Measure, or the Poles, or the Sophisticatoes, or the Dents. There are a lot of bands that aren't covered in there. Not that that's a fault of the book at all, it just has a specific focus.

When you think about the audience for your book ― and obviously all types of people will end up picking it up ― do you imagine it as people who were there, people who have a curiosity about it, or just 14 year old kids who have no idea about these bands?

Honestly, I didn't imagine an audience at all. So much work that I do in music, or photography, or anything, you do it in isolation. I work in my studio, lot of times I'm here by myself. It's the same with retouching photos and putting this book together. It's months of sitting by myself. In a lot of ways, the idea of an audience is foreign, and I think not thinking about an audience helped me to write it the way that I did, because I was able to just say what I was feeling. If I don't think about how people are going to react to this, it's going to be more truthful to what it was to me at the time.

It's got to be the only way to approach it and keep your sanity, I imagine.

It was something I didn't even think about. Who I thought about as the audience was me.

Can you tell me about the seven-inch that comes with the book?

You can get it from the book's dedicated website [www.troubleinthecameraclub.com]. I'm selling it there, then at the launch, and then it will be at Rotate and Soundscapes. The single is two pieces. The first thing is a piece of audio from a Viletones show at the Hotel Isabella that I recorded on a little mono cassette recorder in 1978. The flier that's on the label is for the actual show it's from. It's right before their set, when they're about to start playing. The can hear a fight break out, and Johnny Garbagecan, who was their soundman, you heard him yell to Freddy [Pompeii, guitarist], "Kick his face, Freddy!" At the beginning you hear Freddy say, "Something, something, motherfuckers!" A fist fight breaks out, and this cartoon-style ball was rolling across the room knocking the tables over. You hear that they're about to start "Screaming Fist" because you can just hear that one bass note. That one note creates such a feeling of anticipation and excitement in me because that song is so amazing. The other thing is a radio documentary from a radio station that shall remain unnamed. It's something I recorded off the radio then. I don't know how I knew it would be on, but it's something I've listened to a number of times over the years. It's such a fantastic piece for a number of reasons. It's such a great snapshot of what the media's response to punk rock was like. The guy is being condescending and kind of mocking in his questions and in describing what was happening. But you hear in the audience that it's this really carefree, fun, unpretentious, enjoyable thing. The interview with Leckie is so good. Everything about it is so good. The atmosphere, the room, the band playing, the juxtaposition of "the square" versus "the cool". I thought that was a really fantastic piece that I've listened to every few years for the last 30-something years, and I'm really glad to be able to put that out as an art piece.

Have you had much feedback so far?

Don Pyle: Yeah, actually. All the feedback I've had ― anyone who says anything to my face anyway ― has been overwhelmingly positive. It's been really great, and it's taken me aback. There's been more positive expression than I expected. The last few records I put out have been pretty much totally ignored, so I've gotten used to making something, and no one noticing [laughs].

So this was a little bit of a shift, eh?

Yeah, it has been. And it's easy to feel a bit detached from it because it's taken so long. I think accepting that it was real, and not just in my hands but in other people's hands, as well, has taken me a week or so to get my head around.

For me, what makes it so compelling is that it's so personal. I didn't know what to expect in terms of the writing that would accompany the photos, so beyond the quality of the photos, there's a real sense of magic, that feeling of being a teenager and discovering something. I don't even think you need to have an interest in the specifics of that era of Toronto punk to find it compelling. It's just a great story of being a kid and discovering music.

Thanks, I appreciate that. When I started writing the copy for the book, I easily erased more than I wrote. It took me a long time to find the right tone, the right direction for it. As soon as I started telling any band's story, or describing their history, then I was really aware how I was being dragged in to another book. It was like, "Oh my God, I'm going to write another book! I'm going to write two books! First, the photo book, and now, I have to write the history!" But each time I took a step back and looked at what I was writing, I realized more and more that this has to be about how I came to take these pictures. I wanted it to be the story of how the pictures came to be, not the story of how the Curse or the Ugly came to be. It was really helpful to take that step back. It some ways, I felt like I had to do that to express, as you said, the magic of that time. Thirty-five years later, there's a lot of music that I was really into at that time that I wouldn't necessarily be excited by today. So much of it was that moment. I don't want to read some old guy saying, "This band was great then, but they became crap." There's so much stuff that I love, and I didn't want to be dismissive of where that stuff went, because a lot of people there went to places I didn't find as interesting. But I was thinking a lot about that Sex Pistols... What's the second film? Not The Rock and Roll Swindle?

Oh, The Filth and the Fury.

Yeah, The Filth and the Fury. I found that film so emotional and so moving. And something I thought was so genius about that film was having them in silhouette, so you remain totally in the moment of when this happened. I was thinking about that film, and doing this writing, and trying to remain in that moment, rather than in the present. So I think some of the things I said in the book were kind of silly, or whatever. But they were totally what I was thinking at the time, what I remember thinking then. I think that that's going to convey something more about my feeling taking those pictures, than describing what happened to Teenage Head, or how I feel about their seventh album.

It's a perfect way to frame everything because it's so obviously personal. How many drafts do you think you went through before you came on that particular method?

I don't know if I ever found a method so much as... And I wouldn't even say it was drafts, because it was all over the place. So much writing happens in your head before you put it down on paper. Then you read it later, and you erase 90 percent of it, and start over, thinking, "Oh my God, that's so pretentious. That's boring." It was multiple drafts in multiple sections, and then it was a jigsaw puzzle to pull all this vignettes together to create a narrative flow to the writing. I tried to arrange the photographs in a similar way, so that there was a specific narrative flow to them, not only through time, but the relationship from one band to the next. Like how David Bowie and Bryan Ferry connect to each other, or how the Viletones and the Ugly connect to each other.

To talk a little more about the photos, and I know this is an obvious question, but do you have a favourite photo in the book?

That's something that changes all the time. A couple of people have asked me that, and I had different answers both times. There's one photo right now, a photo of the Viletones at the New Yorker Theatre where [vocalist Steven] Leckie is in the foreground, and he's got a black t-shirt on with the neck and the arms ripped off it. And there's a skull with sunglasses on it, a "Kill 'em all, let God Sort 'em out" kind of thing. He's in the foreground, and Chris Haight is in the background, and he's looking at his bass. He's partially obscured, and there's this really beautiful light coming in from the right side. At different times I fixate on different ones, and go back and look at them, and that's one that's really compelling to me right now. There are a lot of things that I find really interesting about it. One is, there's all this black, open space all around them, but then there's a misty light coming in from the right side that illuminates things and makes the air glow. And Leckie has this dog collar on, and both of them looks really cool. Leckie looks really self-assured and powerful. He looks like a powerful figure on stage, someone who knows that he is in power, and he's here revelling in it. Chris Haight is behind him, and I forget exactly what he's wearing. But there's leather there, he's got his shirt open, there's an iron cross on his guitar strap. Chris Haight is always someone I thought was super cool looking. He's got the real greaser look, that fantastic pompadour. He was always calm, cool, and the quiet guy in the Viletones. So there's a real intensity to his expression there, too. The two of them in that picture are really interesting to me right now.

I love the inclusion of bigger-name people on the same level as the local bands, as part of the same experience. Are you grateful that you had a publisher who didn't insist on more of the famous folks? Did you ever think about not including them at all?

No, I never thought about not including them. When I went through my photographs, I wanted to represent everything I had. There's a picture of Arson that I think is kind of a poor picture. But they were a part of this thing, too. And I wanted them to be a part of this, even if it's just one picture. If I had a picture of any band that was usable, I used it. There were a few things I had that were completely unusable. But if I could include them, they were there. I wish I had so many more photos. Why didn't I take pictures of Sparks opening for Patti Smith? I know the answer, most of the time. I was making $1.30 an hour. Buying film was a significant outlay. So it would be, "Do I buy records, or do I buy film?" A lot of the time, I bought records.

That's pretty fair. It was probably a good idea.

For a lot of the bands there, the idea of "bigger" or "smaller" was less of a concern to me. Locally, everyone started off on the same level. Some of them rose, and years later, we have a totally different perception. Some of them are totally forgotten. Some really great bands have been almost entirely written out of the story by history. It's inevitable. It happens. With Liz Worth's book, Treat Me Like Dirt, that kind of becomes the official history of that time, because it's what people who are 20 years old now can look at and read about. If they read that, they might not know about Drastic Measure, or the Poles, or the Sophisticatoes, or the Dents. There are a lot of bands that aren't covered in there. Not that that's a fault of the book at all, it just has a specific focus.

When you think about the audience for your book ― and obviously all types of people will end up picking it up ― do you imagine it as people who were there, people who have a curiosity about it, or just 14 year old kids who have no idea about these bands?

Honestly, I didn't imagine an audience at all. So much work that I do in music, or photography, or anything, you do it in isolation. I work in my studio, lot of times I'm here by myself. It's the same with retouching photos and putting this book together. It's months of sitting by myself. In a lot of ways, the idea of an audience is foreign, and I think not thinking about an audience helped me to write it the way that I did, because I was able to just say what I was feeling. If I don't think about how people are going to react to this, it's going to be more truthful to what it was to me at the time.

It's got to be the only way to approach it and keep your sanity, I imagine.

It was something I didn't even think about. Who I thought about as the audience was me.

Can you tell me about the seven-inch that comes with the book?

You can get it from the book's dedicated website [www.troubleinthecameraclub.com]. I'm selling it there, then at the launch, and then it will be at Rotate and Soundscapes. The single is two pieces. The first thing is a piece of audio from a Viletones show at the Hotel Isabella that I recorded on a little mono cassette recorder in 1978. The flier that's on the label is for the actual show it's from. It's right before their set, when they're about to start playing. The can hear a fight break out, and Johnny Garbagecan, who was their soundman, you heard him yell to Freddy [Pompeii, guitarist], "Kick his face, Freddy!" At the beginning you hear Freddy say, "Something, something, motherfuckers!" A fist fight breaks out, and this cartoon-style ball was rolling across the room knocking the tables over. You hear that they're about to start "Screaming Fist" because you can just hear that one bass note. That one note creates such a feeling of anticipation and excitement in me because that song is so amazing. The other thing is a radio documentary from a radio station that shall remain unnamed. It's something I recorded off the radio then. I don't know how I knew it would be on, but it's something I've listened to a number of times over the years. It's such a fantastic piece for a number of reasons. It's such a great snapshot of what the media's response to punk rock was like. The guy is being condescending and kind of mocking in his questions and in describing what was happening. But you hear in the audience that it's this really carefree, fun, unpretentious, enjoyable thing. The interview with Leckie is so good. Everything about it is so good. The atmosphere, the room, the band playing, the juxtaposition of "the square" versus "the cool". I thought that was a really fantastic piece that I've listened to every few years for the last 30-something years, and I'm really glad to be able to put that out as an art piece.