A shift occured about halfway through Lana Del Rey's 2017 album Lust for Life, the turning point marked by a song called "Coachella – Woodstock In My Mind." Like that title, the album was split into parallel pieces: contemporary popular artists like the Weeknd, A$AP Rocky, and Playboi Carti featured on one side of the divide, while Stevie Nicks and Sean Ono Lennon conjured vague connections to the Woodstock era on the album's back half. According to Lana lore, "Coachella – Woodstock In My Mind" was inspired by Del Rey's experience seeing Father John Misty perform at Coachella in 2017, one that urged her to pull over on the highway and gather her thoughts in song as she left the desert. "In the next mornin' they put out the warnin' / Tensions were rising over country lines," she wrote, anxious about the missile tests being launched in North Korea. "I turned off the music / Tried to sit and use it / All of the love that I saw that night."

The shift reflected Del Rey's burgeoning sense of social responsibility, a desire for her music's heart and intention to be unmistakably clear and immediately graspable. On Lust for Life's third track, "13 Beaches," she was wallowing in her trademark strain of dissociative trap-pop, letting listeners know that, if they wished to find her, she'd be "Underneath the pines / With the daisies, feelin' hazy / In the ballroom of my mind" — a quintessential Lana lyric that paints a woman so lost in sensuous fantasy that she cannot be reached. By Track 15, "Change," Del Rey is channeling '60's-era protest music over sparse piano, her vocals high in the mix and stripped of any ghostly effects. "Lately, I've been thinkin' it's just someone else's job to care,'' she sings at the top of the song's refrain, wrestling with apathy before quashing it with a commitment: "There's a change gonna come / I don't know where or when / But whenever it does / We'll be here for it."

For someone as prone to sociological analysis as Del Rey — in a recent cover story for Rolling Stone UK, she said that she's "always had a little bit of an intuitive finger on the pulse of culture" — the hedonic playground of Coachella presents a perfect case study for the state of America. Music journalist Jeff Weiss described last year's iteration of the festival as an "artificial desert bloom: a fluorescent rebirth of brilliance and cliché, wavering hope and algorithmic decline, delirious inconvenience and confounding rewards — a tragicomic encapsulation of modern folly and modest triumph." On Lust for Life's 2019 follow-up Norman Fucking Rockwell!, Del Rey — who once loomed as the idol of the flower-crowned flocks on Coachella's grounds, whose voice was transmuted into the siren of Cedric Gervais's fist-pumping, brain-cell-burning "Summertime Sadness" remix — decided to trace this culture of spiraling decadence.

In a way, through her fascination with linking Old Hollywood glamour to modern signifiers of status, Del Rey had always been engaged in this project. But with NFR!, she tried to stand at a remove from her subjects rather than be the protagonist embodying them. The result was some of her sharpest songwriting. On "The Greatest," she tersely encapsulated everything Weiss gestured toward: "L.A. is in flames, it's getting hot / Kanye West is blond and gone / 'Life on Mars' ain't just a song / Oh, the live stream's almost on." She sang these lines — the prophetic power of which has become increasingly apparent over the last four years — in the same resigned tone as when, earlier on the song, she proclaimed, "The culture is lit and I had a ball," pointing at the limited vocabulary at our disposal for describing our collective condition and sense of an end.

NFR! was hailed as a shrewd political record, largely due to its sweeping observations about the Western zeitgeist. The wider acclaim likely also stemmed from Del Rey inhabiting a form of womanhood more legibly empowering than the one she had in her previous work. The first words uttered on the record are "Goddamn man-child," and she goes on to read this fellow for filth: "Your poetry's bad and you blame the news"; "You talk to the walls when the party gets bored of you"; "Why wait for the best when I could have you?" In the thick of Trump's America, rebuking a "man-child" was a sure-fire way to garner many cheers, but this reception revealed something about the long-fraught public treatment of Lana Del Rey.

As Ann Powers wrote in a stan-rousing NPR piece, "Del Rey remains much more invested in describing how people — mostly women — fall apart, how they take risks or otherwise work against their own best interests in the pursuit of pleasure, intimacy and what she still guilelessly calls 'love.'" Though Del Rey tweeted that she didn't agree with any of Powers's points, there's something to be said about the cultural conversations that had to take place before Del Rey could face less scorn for how she's written about her dating history. She herself acknowledged her music's role in initiating those conversations in an otherwise-ill-advised open letter that she posted on Instagram in 2020. "With all of the topics women are finally allowed to explore," she wrote. "I just want to say, over the last ten years, I think it's pathetic that my minor lyrical exploration detailing my sometimes submissive or passive roles in my relationships has often made people say I've set women back hundreds of years."

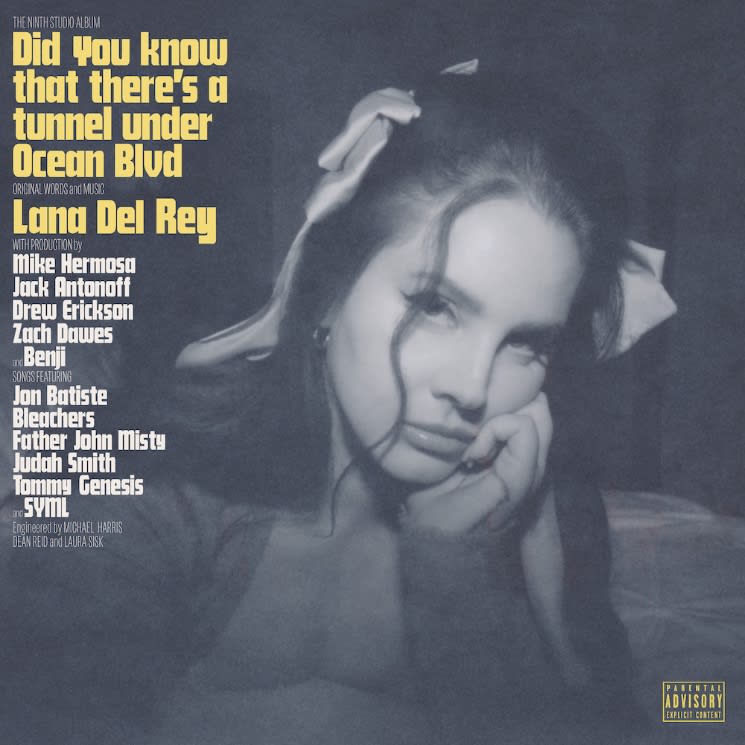

Which leads to a song like "A&W," the second single off Lana Del Rey's ninth album, Did you know that there's a tunnel under Ocean Blvd. It's a lurid, scuzzy, electrifying return to form for an artist who, after crafting three consecutive classic-sounding albums, feels determined to smudge the contours of that irreverent form she created. If Del Rey is sick of having to defend her earlier music against accusations of betraying feminism, then her detractors can feast on "A&W," a chronicle about "the experience of being an American whore." If that earlier music was considered vapid and expressed a demeaning desire for male validation, now Del Rey is likening herself to "a side-piece at 33" and singing, "I mean, look at me / Look at the length of my hair, and my face, the shape of my body / Do you really think I give a damn / What I do after years of just hearing them talking?" And, if the hip hop aesthetics in her songs ever felt stilted, the beat on "A&W" is ferocious — in the second half, it starts choking and gasping, reminiscent of how Britney Spears's "Piece of Me" skewered tabloids and mirrored the distortions of public perception with its screwy synths.

"Fishtail" is just as delicious a kiss-off. Over scurrying hi-hats, Del Rey whisper-raps the kind of head-tilting juxtapositions strewn across her second album, Born to Die. She mentions Ella Fitzgerald right before appropriating contemporary AAVE to rhyme "Feelin' hella rare" with "Baby if you care" (Elsewhere, the four-minute interlude of Instagram pastor Judah Smith shouting a sermon about the dangers of lust bleeds into the Jon Batiste-featuring "Candy Necklace," a song suffused with lust and imagery of tainted innocence, on which Del Rey says, "We were kickin' it like Tribe Called Quest"); She repurposes a filmic lyric from "Jump" off her first record to contrast black-and-white palm trees with her tendency to "[paint] red flags green." These coy references to the old Lana wink to her fans, who will be just as pleased with "Peppers," which speeds up a sample of Tommy Genesis's 2015 track "Angelina" into a hopscotching treat. Here, Del Rey brandishes her familiar style of devil-may-care brattiness with lines like "Take a minute to yourself / Skinny-dip in my mind" and "Got a knife in my jacket / Honey on the vine."

Counterposing these playful excursions are songs that spotlight Del Rey as an exquisitely thoughtful and fearless writer, now intent on wading further into life's soft spots. Throughout Did you know, she calls for her loved ones by name, imploring them to understand the sanctity and responsibility of being in this world together. Opening track "The Grants," starts with Melodye Perry, Pattie Howard, and Shikena Jones harmonizing a line that can sound both like "I'm gonna take mine of you with me" and "I'm gonna take mind of you with me." The effect is one of a bridge being built between memory, intimacy, and possession, and not long after, Del Rey sings of her pastor telling her that memory is all we take when we leave. So, she imagines what she might bring: "My sister's first-born child / I'm gonna take that too with me / My grandmother's last smile / I'm gonna take that too with me."

If Del Rey's earlier work concerned itself with cultural memory — American narratives and iconography, their affordances and erasures — Did you know explores personal memory, primarily through the branch of family lineage. How do we carry the ones we've lost with us, and how do we keep those still here close? "Fingertips" brilliantly simulates the uneven, non-linear space of consciousness with strings entering and peaking at irregular intervals while Del Rey's lissome voice meanders between milestones and forking possibilities — everything melting into an indistinguishable pool of significance. On "Kintsugi," she contemplates the deaths of relatives and the ways she sought to endure them. "But daddy, I miss them / I'm at the Roadrunner Café / Probably runnin' away from the feelings today," she sings in one of the album's most heart-wrenching moments, capturing the undying yearning to call home before a memory of unfathomable lightness sweeps her up: like a grainy reel spinning in her mind, she recalls a time her family gathered and sang folk songs from the '40s: "Even the fourteen-year-old knew 'Froggie Came A-Courtin' / How do my blood relatives know all of these songs?"

Beyond simply toggling between different Lana eras, several songs on Did you know synthesize the personality-driven pop genius and the hyper-specific singer-songwriter, demonstrating how tight a grasp she maintains on her multifaceted vision and how drastically she's evolved as an artist. "Sweet" pairs her most wistful 50's-style vibrato with a line like "I've got magic in my hand, stars in my eyes," only to undercut it with her intoning, "If you want some basic bitch, go to the Beverly Center and find her." When the trio of gospel singers who open "The Grants" return on the title track to add an air of holiness to the final chorus, they echo, "Open me up / Tell me you like it / Fuck me to death / Love me until I love myself." Then comes the project's thesis: "Don't forget me / Like the tunnel under Ocean Boulevard." It's a melding of a Harry Nilsson lyric and a piece of Los Angeles trivia that pulled at the singular heartstrings of Lana Del Rey, someone who hopes — above all else — for her loved ones to keep her close and for them to see her completely. If that hope radiates in her music, it's doing everything it ought to.

(Interscope/Universal)The shift reflected Del Rey's burgeoning sense of social responsibility, a desire for her music's heart and intention to be unmistakably clear and immediately graspable. On Lust for Life's third track, "13 Beaches," she was wallowing in her trademark strain of dissociative trap-pop, letting listeners know that, if they wished to find her, she'd be "Underneath the pines / With the daisies, feelin' hazy / In the ballroom of my mind" — a quintessential Lana lyric that paints a woman so lost in sensuous fantasy that she cannot be reached. By Track 15, "Change," Del Rey is channeling '60's-era protest music over sparse piano, her vocals high in the mix and stripped of any ghostly effects. "Lately, I've been thinkin' it's just someone else's job to care,'' she sings at the top of the song's refrain, wrestling with apathy before quashing it with a commitment: "There's a change gonna come / I don't know where or when / But whenever it does / We'll be here for it."

For someone as prone to sociological analysis as Del Rey — in a recent cover story for Rolling Stone UK, she said that she's "always had a little bit of an intuitive finger on the pulse of culture" — the hedonic playground of Coachella presents a perfect case study for the state of America. Music journalist Jeff Weiss described last year's iteration of the festival as an "artificial desert bloom: a fluorescent rebirth of brilliance and cliché, wavering hope and algorithmic decline, delirious inconvenience and confounding rewards — a tragicomic encapsulation of modern folly and modest triumph." On Lust for Life's 2019 follow-up Norman Fucking Rockwell!, Del Rey — who once loomed as the idol of the flower-crowned flocks on Coachella's grounds, whose voice was transmuted into the siren of Cedric Gervais's fist-pumping, brain-cell-burning "Summertime Sadness" remix — decided to trace this culture of spiraling decadence.

In a way, through her fascination with linking Old Hollywood glamour to modern signifiers of status, Del Rey had always been engaged in this project. But with NFR!, she tried to stand at a remove from her subjects rather than be the protagonist embodying them. The result was some of her sharpest songwriting. On "The Greatest," she tersely encapsulated everything Weiss gestured toward: "L.A. is in flames, it's getting hot / Kanye West is blond and gone / 'Life on Mars' ain't just a song / Oh, the live stream's almost on." She sang these lines — the prophetic power of which has become increasingly apparent over the last four years — in the same resigned tone as when, earlier on the song, she proclaimed, "The culture is lit and I had a ball," pointing at the limited vocabulary at our disposal for describing our collective condition and sense of an end.

NFR! was hailed as a shrewd political record, largely due to its sweeping observations about the Western zeitgeist. The wider acclaim likely also stemmed from Del Rey inhabiting a form of womanhood more legibly empowering than the one she had in her previous work. The first words uttered on the record are "Goddamn man-child," and she goes on to read this fellow for filth: "Your poetry's bad and you blame the news"; "You talk to the walls when the party gets bored of you"; "Why wait for the best when I could have you?" In the thick of Trump's America, rebuking a "man-child" was a sure-fire way to garner many cheers, but this reception revealed something about the long-fraught public treatment of Lana Del Rey.

As Ann Powers wrote in a stan-rousing NPR piece, "Del Rey remains much more invested in describing how people — mostly women — fall apart, how they take risks or otherwise work against their own best interests in the pursuit of pleasure, intimacy and what she still guilelessly calls 'love.'" Though Del Rey tweeted that she didn't agree with any of Powers's points, there's something to be said about the cultural conversations that had to take place before Del Rey could face less scorn for how she's written about her dating history. She herself acknowledged her music's role in initiating those conversations in an otherwise-ill-advised open letter that she posted on Instagram in 2020. "With all of the topics women are finally allowed to explore," she wrote. "I just want to say, over the last ten years, I think it's pathetic that my minor lyrical exploration detailing my sometimes submissive or passive roles in my relationships has often made people say I've set women back hundreds of years."

Which leads to a song like "A&W," the second single off Lana Del Rey's ninth album, Did you know that there's a tunnel under Ocean Blvd. It's a lurid, scuzzy, electrifying return to form for an artist who, after crafting three consecutive classic-sounding albums, feels determined to smudge the contours of that irreverent form she created. If Del Rey is sick of having to defend her earlier music against accusations of betraying feminism, then her detractors can feast on "A&W," a chronicle about "the experience of being an American whore." If that earlier music was considered vapid and expressed a demeaning desire for male validation, now Del Rey is likening herself to "a side-piece at 33" and singing, "I mean, look at me / Look at the length of my hair, and my face, the shape of my body / Do you really think I give a damn / What I do after years of just hearing them talking?" And, if the hip hop aesthetics in her songs ever felt stilted, the beat on "A&W" is ferocious — in the second half, it starts choking and gasping, reminiscent of how Britney Spears's "Piece of Me" skewered tabloids and mirrored the distortions of public perception with its screwy synths.

"Fishtail" is just as delicious a kiss-off. Over scurrying hi-hats, Del Rey whisper-raps the kind of head-tilting juxtapositions strewn across her second album, Born to Die. She mentions Ella Fitzgerald right before appropriating contemporary AAVE to rhyme "Feelin' hella rare" with "Baby if you care" (Elsewhere, the four-minute interlude of Instagram pastor Judah Smith shouting a sermon about the dangers of lust bleeds into the Jon Batiste-featuring "Candy Necklace," a song suffused with lust and imagery of tainted innocence, on which Del Rey says, "We were kickin' it like Tribe Called Quest"); She repurposes a filmic lyric from "Jump" off her first record to contrast black-and-white palm trees with her tendency to "[paint] red flags green." These coy references to the old Lana wink to her fans, who will be just as pleased with "Peppers," which speeds up a sample of Tommy Genesis's 2015 track "Angelina" into a hopscotching treat. Here, Del Rey brandishes her familiar style of devil-may-care brattiness with lines like "Take a minute to yourself / Skinny-dip in my mind" and "Got a knife in my jacket / Honey on the vine."

Counterposing these playful excursions are songs that spotlight Del Rey as an exquisitely thoughtful and fearless writer, now intent on wading further into life's soft spots. Throughout Did you know, she calls for her loved ones by name, imploring them to understand the sanctity and responsibility of being in this world together. Opening track "The Grants," starts with Melodye Perry, Pattie Howard, and Shikena Jones harmonizing a line that can sound both like "I'm gonna take mine of you with me" and "I'm gonna take mind of you with me." The effect is one of a bridge being built between memory, intimacy, and possession, and not long after, Del Rey sings of her pastor telling her that memory is all we take when we leave. So, she imagines what she might bring: "My sister's first-born child / I'm gonna take that too with me / My grandmother's last smile / I'm gonna take that too with me."

If Del Rey's earlier work concerned itself with cultural memory — American narratives and iconography, their affordances and erasures — Did you know explores personal memory, primarily through the branch of family lineage. How do we carry the ones we've lost with us, and how do we keep those still here close? "Fingertips" brilliantly simulates the uneven, non-linear space of consciousness with strings entering and peaking at irregular intervals while Del Rey's lissome voice meanders between milestones and forking possibilities — everything melting into an indistinguishable pool of significance. On "Kintsugi," she contemplates the deaths of relatives and the ways she sought to endure them. "But daddy, I miss them / I'm at the Roadrunner Café / Probably runnin' away from the feelings today," she sings in one of the album's most heart-wrenching moments, capturing the undying yearning to call home before a memory of unfathomable lightness sweeps her up: like a grainy reel spinning in her mind, she recalls a time her family gathered and sang folk songs from the '40s: "Even the fourteen-year-old knew 'Froggie Came A-Courtin' / How do my blood relatives know all of these songs?"

Beyond simply toggling between different Lana eras, several songs on Did you know synthesize the personality-driven pop genius and the hyper-specific singer-songwriter, demonstrating how tight a grasp she maintains on her multifaceted vision and how drastically she's evolved as an artist. "Sweet" pairs her most wistful 50's-style vibrato with a line like "I've got magic in my hand, stars in my eyes," only to undercut it with her intoning, "If you want some basic bitch, go to the Beverly Center and find her." When the trio of gospel singers who open "The Grants" return on the title track to add an air of holiness to the final chorus, they echo, "Open me up / Tell me you like it / Fuck me to death / Love me until I love myself." Then comes the project's thesis: "Don't forget me / Like the tunnel under Ocean Boulevard." It's a melding of a Harry Nilsson lyric and a piece of Los Angeles trivia that pulled at the singular heartstrings of Lana Del Rey, someone who hopes — above all else — for her loved ones to keep her close and for them to see her completely. If that hope radiates in her music, it's doing everything it ought to.