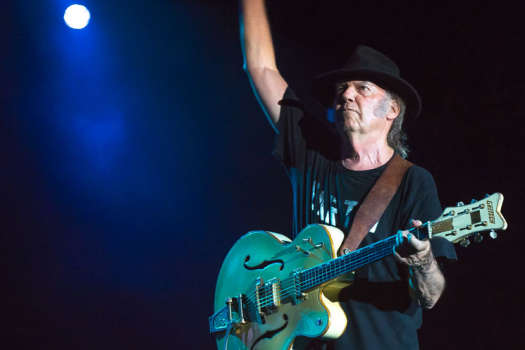

Where is the love?

Right now it's on Toronto's Dundas Street West. We recently visited Joel Eel (born Chol Eul) at an apartment-cum-studio that he's currently sharing with DJ friend Waseem Dabdoub (aka Wasserman), and Bruno the Dog (an actual dog). It's spitting distance from Bambi's — one of the only consistent venues in the city for proper electronic music — and the more recent addition of label and record store Invisible City.

We're basically looking at a tight little triptych of creativity that could lead to some interesting partnerships down the line. "I feel that having a studio around here will open up a lot more collaborations," Eul tells Exclaim! "Maybe before a show, I might jam with someone or hang out up here afterwards, who knows?"

This would be nothing new for Eul, though. For his latest album, Performing A Crime, he called upon long-time friend Brian Wong (better known as Gingy) to help flesh out the record. In order to finesse everything, the two hunkered down for 15 days in the Treatment Centre, a different studio run by Matthew Butterworth. Despite having access to "every synth and drum machine you could think of" for that fortnight, Eul didn't touch a thing. "The ideas were already there, and it was just about making everything fit well, sonically," he says. "I didn't want to use equipment just for nostalgia's sake. It was more about the ideas, and whether or not those ideas translated with the equipment I already had."

While his previous setup focused heavily on 909 replicas and a complicated modular setup, Eul (who might be one of the few who haven't gone deep down the modular rabbit hole) chose to limit himself to two patches — Shapeshifter and Mutant BD9 — and Elektron's Digitakt drum machine/sampler, for the guts of the album.

"The record is probably 90 percent Digitakt and 10 percent modular," says Eul. "I wanted to see what kinds of sounds I could develop with just one instrument. Actually, I just used all the default samples from the Digitakt too [laughs]. I was also travelling a lot [through London and Berlin] when I wrote the album, so sometimes it was just about using what I had with me. Restricting myself came from two reasons, really: one, out of convenience, but then also seeing what I could write without getting too complex."

Still, probably the most important instrument that Eul used on Performing A Crime is one that he carries around with him at all times: his voice. Having played in "shitty" punk bands since the age of 14, lyrics are something that he's always used in music, so it seemed only natural to keep that up. "I think it adds another layer to the music and helps a lot in putting forth an idea," Eul explains. "It also really helps to distinguish me from what other people are doing with this style of music. Industrial techno, EBM, everything in that vicinity is hyper-masculine. Conceptually, and through lyricism, I tried to reverse or remove the barrier of those stereotypes and add a different flavour."

Just like vocals aren't particularly frequent in EBM, concepts are even rarer, and notions of romanticism, rarer still. Yet, Eul has delivered on all of these with Performing A Crime, and somehow manages to make a thought-provoking record that's also club-ready. "It's a love album for the dance floor," says Eul. "It's about how one can be seen as a criminal, while in a relationship. You might be doing something that is positive in your headspace, but it could be projected in a different perspective. It's touching upon my own experiences from being in relationships, but also exploring expression towards intimacy and how that's been diluted too. The title track is really the core concept of the album, but there are other ideas on there too."

The opener, "Sapphire," tackles panic disorder, something Eul was diagnosed with last year, while "Man of Colour, My Machine" looks at the shells we've all been dealt with and how they alter people's perceptions of us. "Leather Love Letter" too has something to say, "that one goes back to the metaphor of 'you can't write on leather,' so you can't express your love on a material that's kind of course," says Eul. "It's conversing about how love is a diminished form of romanticism these days. You don't get long, expressive conversations anymore, it's very short: like, 'hanging with bae,' and IRLY, just the acronym and not the actual words."

Eul has pulled off a neat trick here: he dove head-first into the wires and pulled out some conceptual heartbreak. Not to mention soldering it to a style that's never been one for sentiment. "I think it's very difficult to see poetry in something that's aggressive," says Eul. "This kind of music is immediately in your face, so it's hard to see an idea behind it. There's a real challenge in drawing some feeling from equipment that is kind of cold, and the lyrics do help with that, for sure. I don't know if people will necessarily feel like this is a love album, but to me it absolutely is."

Right now it's on Toronto's Dundas Street West. We recently visited Joel Eel (born Chol Eul) at an apartment-cum-studio that he's currently sharing with DJ friend Waseem Dabdoub (aka Wasserman), and Bruno the Dog (an actual dog). It's spitting distance from Bambi's — one of the only consistent venues in the city for proper electronic music — and the more recent addition of label and record store Invisible City.

We're basically looking at a tight little triptych of creativity that could lead to some interesting partnerships down the line. "I feel that having a studio around here will open up a lot more collaborations," Eul tells Exclaim! "Maybe before a show, I might jam with someone or hang out up here afterwards, who knows?"

This would be nothing new for Eul, though. For his latest album, Performing A Crime, he called upon long-time friend Brian Wong (better known as Gingy) to help flesh out the record. In order to finesse everything, the two hunkered down for 15 days in the Treatment Centre, a different studio run by Matthew Butterworth. Despite having access to "every synth and drum machine you could think of" for that fortnight, Eul didn't touch a thing. "The ideas were already there, and it was just about making everything fit well, sonically," he says. "I didn't want to use equipment just for nostalgia's sake. It was more about the ideas, and whether or not those ideas translated with the equipment I already had."

While his previous setup focused heavily on 909 replicas and a complicated modular setup, Eul (who might be one of the few who haven't gone deep down the modular rabbit hole) chose to limit himself to two patches — Shapeshifter and Mutant BD9 — and Elektron's Digitakt drum machine/sampler, for the guts of the album.

"The record is probably 90 percent Digitakt and 10 percent modular," says Eul. "I wanted to see what kinds of sounds I could develop with just one instrument. Actually, I just used all the default samples from the Digitakt too [laughs]. I was also travelling a lot [through London and Berlin] when I wrote the album, so sometimes it was just about using what I had with me. Restricting myself came from two reasons, really: one, out of convenience, but then also seeing what I could write without getting too complex."

Still, probably the most important instrument that Eul used on Performing A Crime is one that he carries around with him at all times: his voice. Having played in "shitty" punk bands since the age of 14, lyrics are something that he's always used in music, so it seemed only natural to keep that up. "I think it adds another layer to the music and helps a lot in putting forth an idea," Eul explains. "It also really helps to distinguish me from what other people are doing with this style of music. Industrial techno, EBM, everything in that vicinity is hyper-masculine. Conceptually, and through lyricism, I tried to reverse or remove the barrier of those stereotypes and add a different flavour."

Just like vocals aren't particularly frequent in EBM, concepts are even rarer, and notions of romanticism, rarer still. Yet, Eul has delivered on all of these with Performing A Crime, and somehow manages to make a thought-provoking record that's also club-ready. "It's a love album for the dance floor," says Eul. "It's about how one can be seen as a criminal, while in a relationship. You might be doing something that is positive in your headspace, but it could be projected in a different perspective. It's touching upon my own experiences from being in relationships, but also exploring expression towards intimacy and how that's been diluted too. The title track is really the core concept of the album, but there are other ideas on there too."

The opener, "Sapphire," tackles panic disorder, something Eul was diagnosed with last year, while "Man of Colour, My Machine" looks at the shells we've all been dealt with and how they alter people's perceptions of us. "Leather Love Letter" too has something to say, "that one goes back to the metaphor of 'you can't write on leather,' so you can't express your love on a material that's kind of course," says Eul. "It's conversing about how love is a diminished form of romanticism these days. You don't get long, expressive conversations anymore, it's very short: like, 'hanging with bae,' and IRLY, just the acronym and not the actual words."

Eul has pulled off a neat trick here: he dove head-first into the wires and pulled out some conceptual heartbreak. Not to mention soldering it to a style that's never been one for sentiment. "I think it's very difficult to see poetry in something that's aggressive," says Eul. "This kind of music is immediately in your face, so it's hard to see an idea behind it. There's a real challenge in drawing some feeling from equipment that is kind of cold, and the lyrics do help with that, for sure. I don't know if people will necessarily feel like this is a love album, but to me it absolutely is."