Australian-born Alex Cameron is best described as music's answer to Danny McBride. Cameron is as much a fiction author as he is a singer, and the majority of his discography consists of vignettes penned from the perspective of the type of men that McBride embodies in his characters, whether it be Kenny Powers or Jesse Gemstone. They're crude, perverted, and constantly trying to cover up their self-loathing with arrogance. Both Cameron and McBride use the satirization of these characters for humour and social commentary, but there's also a sense of empathy in their writing; if they had just make a couple correct decisions and had a strong mentor in their life, things could've turned out different. Yet, their characters never cash in on the opportunities to change for the better, and become increasingly isolated from friends, family, and society as a result.

Isolation is an especially strong theme across Cameron's discography. Whether speaking from a down-and-out character he's formulated or passionately defending sex workers, he clearly sees isolation as a serious ailment, one that can have disastrous psychological consequences. Those ideas translate to Oxy Music, but the difference is that Cameron seems to be far more sympathetic for his characters this time around.

It's partly because he's no longer talking about the sleaziest, creepiest guy you can think about. Inspired by the homeless addicts he saw while living in New York and Nico Walker's autofictional book Cherry, the majority of the record sees Cameron playing the role of a drug addict, delving into the ostracism that comes with the abuse of opioids. He sings about being afraid of his parents finding bruises on his arms on "Hold The Line," and tells his lover to leave him if he ever overdoses on "Breakdown." When he says. "there's only room for one in the k-hole," it summarizes home his thoughts toward addiction; that it affects everyone around the addict, and the distance it creates between them and their loved ones often creates a vicious cycle that leads them to use drugs even more.

When Cameron isn't talking about drug addiction on Oxy Music, he's still focused on the topic of isolation. The two songs that open the record, "Best Life" and "Sara Jo," speak about a different type of obsession, of being terminally online in the quarantine era. "Sara Jo" specifically is one of the best critiques of online culture in recent memory. "One thing you do, is never fuck with my family," Cameron croons, before listing off ways that the internet has done just that. They've told his brother his kids will die from vaccination, a divisive tool of misinformation that has made plenty a family group chat a war zone. They've told his mother she's ugly, and his father that he doesn't need therapy no matter what. It's a different type of isolation than drug addiction, but a self-inflicted isolation nonetheless. In the misinformation era, anyone's confirmation bias can lead to them adopting an aggressive, dogmatic ideology that can range from hateful and dangerous, to simply unpleasant to be around.

Through all of these stories, Cameron is able to stray away from being preachy or judgemental the way he always has: through humor. He's not just a great writer, but an incredibly funny one, and similar to a great stand-up comedian, it makes it easy to listen to what he has to say. "Cancel Culture" is a cleverly-named song clearly meant to bait both the people who get excited to dogpile onto anything they deem Roganesque, and the people who are actively seeking out "woke mob" criticism — it ends up being a song about cultural appropriation. "Prescription Refill" comes off as the typical drug-love metaphor, but he's not talking about cocaine or heroin, and is likening the way his lover brightens their outlook on life to prescribed Transitions lenses. These moments serve to remind the listener that you never really know if Cameron is joking or being serious, if he's communicating his own feelings or those from a character he's dreamed up, and that despite the serious material on the record, he's still making music to have fun.

Cameron's subject matter takes up so much focus on Oxy Music that it can be hard to remember the other major part of it, the instrumentation. In a statement released alongside the LP, Cameron contends that his band "is a band that can hang with any other band, dead or alive." The arrangement and production on Oxy Music certainly backs that up on a technical level: the songs are performed perfectly, each part of a song perfectly in tune with the other. However, the songs do leave something to be desired compared to previous Cameron records. With albums like 2013's Jumping the Shark and 2017's Forced Witness, the strong '80s influence that ran through the instrumentals behind Cameron complimented the characters he was writing: you could imagine them wearing suits with big collars, three or four buttons undone to show a gaudy necklace and an abundance of chest hair. The style of music took on the personality of the protagonist in that they were in their prime when it was most popular. On Oxy Music, the synthpop and Springsteen worship seems to be more of a comfort-zone choice than anything else. It isn't bad by any stretch, but it doesn't elevate Cameron's performances or the immersion he attempts to create.

The lack of instrumental ambition does not stop Oxy Music from being an enjoyable, thought-provoking experience. It is not the first album to tackle the psyche of a drug addict, and it won't be the last. But it is the only album to address the issue from Alex Cameron's unique way of making music, and that alone makes it a worthwhile listen. It forces listeners to humanize addicts of all kinds, to think of the type of support they need in order to simply feel comfortable being around the people they love. With a opioid crisis tearing through the world, music that describes addicts as more than junkies is important. Sharing this is only part of the job: nobody wants to be lectured on how they need to care more about people they may not even know. Oxy Music's greatest strength is that it makes the plight of an addict easy to understand and sympathize with, and may even help addicts who tune in feel less alone.

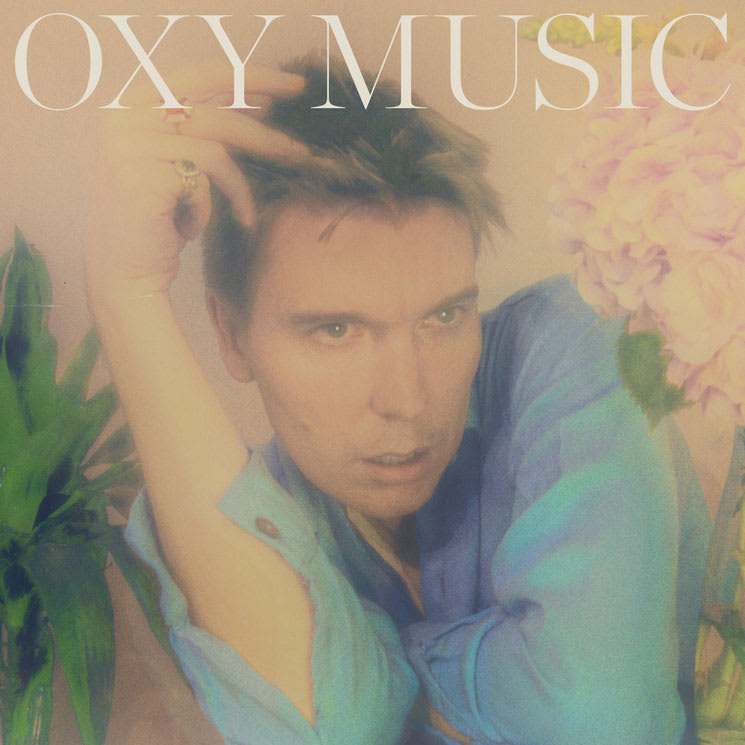

(Secretly Canadian)Isolation is an especially strong theme across Cameron's discography. Whether speaking from a down-and-out character he's formulated or passionately defending sex workers, he clearly sees isolation as a serious ailment, one that can have disastrous psychological consequences. Those ideas translate to Oxy Music, but the difference is that Cameron seems to be far more sympathetic for his characters this time around.

It's partly because he's no longer talking about the sleaziest, creepiest guy you can think about. Inspired by the homeless addicts he saw while living in New York and Nico Walker's autofictional book Cherry, the majority of the record sees Cameron playing the role of a drug addict, delving into the ostracism that comes with the abuse of opioids. He sings about being afraid of his parents finding bruises on his arms on "Hold The Line," and tells his lover to leave him if he ever overdoses on "Breakdown." When he says. "there's only room for one in the k-hole," it summarizes home his thoughts toward addiction; that it affects everyone around the addict, and the distance it creates between them and their loved ones often creates a vicious cycle that leads them to use drugs even more.

When Cameron isn't talking about drug addiction on Oxy Music, he's still focused on the topic of isolation. The two songs that open the record, "Best Life" and "Sara Jo," speak about a different type of obsession, of being terminally online in the quarantine era. "Sara Jo" specifically is one of the best critiques of online culture in recent memory. "One thing you do, is never fuck with my family," Cameron croons, before listing off ways that the internet has done just that. They've told his brother his kids will die from vaccination, a divisive tool of misinformation that has made plenty a family group chat a war zone. They've told his mother she's ugly, and his father that he doesn't need therapy no matter what. It's a different type of isolation than drug addiction, but a self-inflicted isolation nonetheless. In the misinformation era, anyone's confirmation bias can lead to them adopting an aggressive, dogmatic ideology that can range from hateful and dangerous, to simply unpleasant to be around.

Through all of these stories, Cameron is able to stray away from being preachy or judgemental the way he always has: through humor. He's not just a great writer, but an incredibly funny one, and similar to a great stand-up comedian, it makes it easy to listen to what he has to say. "Cancel Culture" is a cleverly-named song clearly meant to bait both the people who get excited to dogpile onto anything they deem Roganesque, and the people who are actively seeking out "woke mob" criticism — it ends up being a song about cultural appropriation. "Prescription Refill" comes off as the typical drug-love metaphor, but he's not talking about cocaine or heroin, and is likening the way his lover brightens their outlook on life to prescribed Transitions lenses. These moments serve to remind the listener that you never really know if Cameron is joking or being serious, if he's communicating his own feelings or those from a character he's dreamed up, and that despite the serious material on the record, he's still making music to have fun.

Cameron's subject matter takes up so much focus on Oxy Music that it can be hard to remember the other major part of it, the instrumentation. In a statement released alongside the LP, Cameron contends that his band "is a band that can hang with any other band, dead or alive." The arrangement and production on Oxy Music certainly backs that up on a technical level: the songs are performed perfectly, each part of a song perfectly in tune with the other. However, the songs do leave something to be desired compared to previous Cameron records. With albums like 2013's Jumping the Shark and 2017's Forced Witness, the strong '80s influence that ran through the instrumentals behind Cameron complimented the characters he was writing: you could imagine them wearing suits with big collars, three or four buttons undone to show a gaudy necklace and an abundance of chest hair. The style of music took on the personality of the protagonist in that they were in their prime when it was most popular. On Oxy Music, the synthpop and Springsteen worship seems to be more of a comfort-zone choice than anything else. It isn't bad by any stretch, but it doesn't elevate Cameron's performances or the immersion he attempts to create.

The lack of instrumental ambition does not stop Oxy Music from being an enjoyable, thought-provoking experience. It is not the first album to tackle the psyche of a drug addict, and it won't be the last. But it is the only album to address the issue from Alex Cameron's unique way of making music, and that alone makes it a worthwhile listen. It forces listeners to humanize addicts of all kinds, to think of the type of support they need in order to simply feel comfortable being around the people they love. With a opioid crisis tearing through the world, music that describes addicts as more than junkies is important. Sharing this is only part of the job: nobody wants to be lectured on how they need to care more about people they may not even know. Oxy Music's greatest strength is that it makes the plight of an addict easy to understand and sympathize with, and may even help addicts who tune in feel less alone.