Fox Rich has spent over two decades fighting to reunite her family in Louisiana. A working mother of six, every year she hopes it will be the last year of filing papers, calling judges and meeting with lawyers to release her husband, Rob, from prison. She is hoping to revoke his 60-year sentence for a robbery they both committed and that she also served time for.

At a certain point during Time, you may wonder about seeing what has come to be expected in a documentary about the broken and racist American criminal justice system — the ups and downs of the court battles, a life reduced to boxes of legal documents. But these things do not get time in this story — they have already taken enough. Director Garrett Bradley instead makes this film about everyone outside of prison waiting: the long days and routines, children growing up without their father, a wife raising them without her husband.

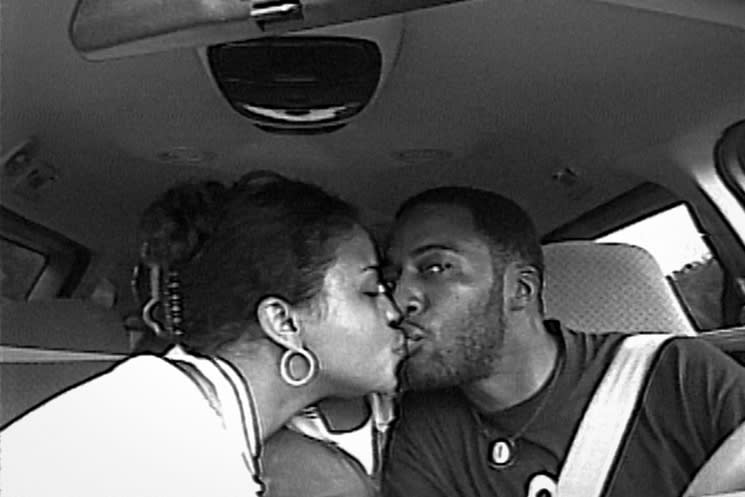

Bradley first met Fox (also referred to as Sibil), a passionate abolitionist, while filming her 2017 short film Alone, and Time was originally conceptualized as a sister film. But all of that changed when Fox handed Bradley 19 years of home movies. A day selected from this archive of diary-like recordings may show Fox in the car with the kids, hanging out with a friend by the pool, or addressing Rob while pregnant with their twins. She documents seemingly every moment of her life and her children's lives. Time braids these diaries throughout the film with new footage, the black and white treatment adding a timelessness to the recordings (while also aesthetically tying together all the different types of formats). Visually, the years appear to blend, suspended: there is only before and after prison.

Time does not hide its stylized form, but embraces it, and the result is an intensely moving, empathetic account of an unshakable love and a family thriving in defiance of a broken system. With the narration from Fox, and piano compositions of Emahoy Tsegue Maryam Guebrou scoring many scenes, sometimes it feels like we are being told a story. Even the editing seems to be taking a cue from Fox's cadence, rather than following a strict narrative structure. The piercing subtleties in this film hit hardest, and where Bradley's gift for the medium really shines. The injustices that have kept Rob incarcerated for so long are mentioned briefly throughout, but they cut through the images of a strong family and punctuate scenes where his children are now grown, smart young men — without their father.

Despite Fox's unwavering tone, another call that doesn't get Rob home before the twins' 18th birthday is enough to remember that this story is depressingly familiar for Black Americans. In a rare moment, Fox lets out her frustration, but just as quickly collects herself and moves onto the next thing in her busy day. As Freedom, one of the twins, says in the film, "The family has a very strong image, but there is a lot of hurt and pain underneath."

(Amazon Studios)At a certain point during Time, you may wonder about seeing what has come to be expected in a documentary about the broken and racist American criminal justice system — the ups and downs of the court battles, a life reduced to boxes of legal documents. But these things do not get time in this story — they have already taken enough. Director Garrett Bradley instead makes this film about everyone outside of prison waiting: the long days and routines, children growing up without their father, a wife raising them without her husband.

Bradley first met Fox (also referred to as Sibil), a passionate abolitionist, while filming her 2017 short film Alone, and Time was originally conceptualized as a sister film. But all of that changed when Fox handed Bradley 19 years of home movies. A day selected from this archive of diary-like recordings may show Fox in the car with the kids, hanging out with a friend by the pool, or addressing Rob while pregnant with their twins. She documents seemingly every moment of her life and her children's lives. Time braids these diaries throughout the film with new footage, the black and white treatment adding a timelessness to the recordings (while also aesthetically tying together all the different types of formats). Visually, the years appear to blend, suspended: there is only before and after prison.

Time does not hide its stylized form, but embraces it, and the result is an intensely moving, empathetic account of an unshakable love and a family thriving in defiance of a broken system. With the narration from Fox, and piano compositions of Emahoy Tsegue Maryam Guebrou scoring many scenes, sometimes it feels like we are being told a story. Even the editing seems to be taking a cue from Fox's cadence, rather than following a strict narrative structure. The piercing subtleties in this film hit hardest, and where Bradley's gift for the medium really shines. The injustices that have kept Rob incarcerated for so long are mentioned briefly throughout, but they cut through the images of a strong family and punctuate scenes where his children are now grown, smart young men — without their father.

Despite Fox's unwavering tone, another call that doesn't get Rob home before the twins' 18th birthday is enough to remember that this story is depressingly familiar for Black Americans. In a rare moment, Fox lets out her frustration, but just as quickly collects herself and moves onto the next thing in her busy day. As Freedom, one of the twins, says in the film, "The family has a very strong image, but there is a lot of hurt and pain underneath."