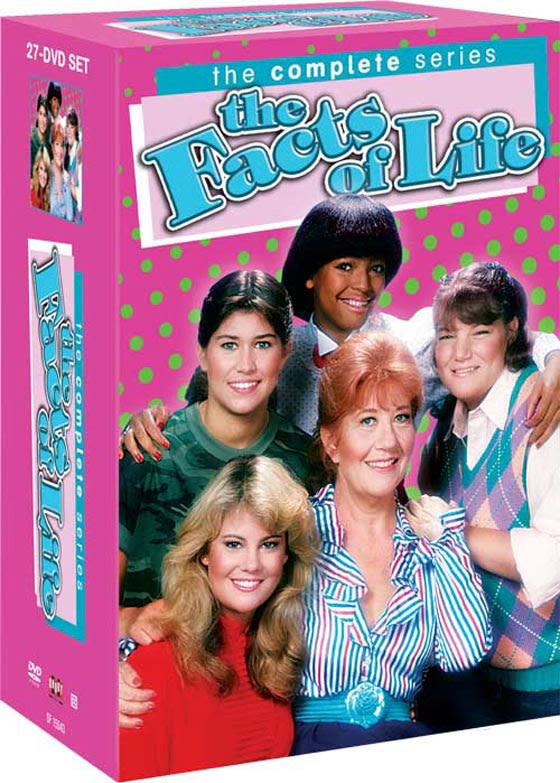

In the pilot episode of the Diff'rent Strokes spinoff, The Facts of Life, Mrs. Garrett (Charlotte Rae) — ostensibly the chambermaid of an all-girls private school — discovers that Cindy (Julie Anne Haddock) is struggling with gender performance issues after Blair (Lisa Whelchel) suggests her boyish disposition and tendency to hug and touch girls frequently is strange. In response, Mrs. Garrett approaches Blair and passive-aggressively implies that she's a huge slut. They boil it down to a lesson about perception and making snap judgements, but the resolution — Cindy putting on a dress and discovering the wonderful world of passive objectivity — is a tad disconcerting. The underlying message here is that women must adhere to heteronormative gender standards and be a mix of chaste and shrewdly manipulative to succeed in the world.

Now, this was 1979, which is why the episode in which Blair develops a crush on a "retard" and tries to teach him to paint exists, but the irony is that Facts was considered progressive. One of the more consistent trajectory gags throughout the series involves the girls doling out clunky bon mots at the many male guest stars when they make a broadly sexist comment about women cooking or having babies. It's a nice assertion, but as the seasons progress, it's clear that the main social motivator for all of the central characters — even motorcycle-riding Jo (Nancy McKeon) when they run off to France for a fantastically awful TV movie adventure that's included with this box set — is finding a moderately attractive man with money to pay for the litter of kids they plan to have. Only Natalie (Mindy Cohn) stays somewhat free from this ideological trap — mainly, the show seems to imply, because she's fat and therefore unattractive (so she'll have to work). Despite this, even she concedes to this convention in later seasons.

Like most '80s television, the format is template-based didacticism, with an issue — racism, cheating on tests, drinking, and so on — being raised within the first couple of minutes in an episode only to come around to an overly simplified, moralistic observation by the 20-minute mark. In truth, it's painful to watch now, but at the time, it was funnier than much of the traditionalist twaddle flooding the airwaves.

From the perspective of cultural analysis, the series is a very fascinating watch in a modern context. The pseudo-progressive attitudes towards issues that they were still handling in a relatively offensive manner — Blair's differently abled "comedienne" cousin (Geri Jewell) routinely pops up and cracks jokes about her disposition (she suffers from muscular dystrophy) merely being a symptom of intoxication — is, in an overly sanitized, morally vain world, a nice guilty pleasure.

The box set includes some relatively new interview featurettes with the original season one cast of the show. The discussion is mostly about how the show came to be and why they completely retooled it for season two and axed two-thirds of the cast members (including a young and exceedingly awkward Molly Ringwald). Some of the actresses are bitter, while others acknowledge the experience for what it was. No one addresses the last few seasons, in which Mrs. Garrett opens a novelty shop and hires a sexy young construction worker in the form of George Clooney (who has a kick-ass mullet) to fix it up.

(Shout! Factory)Now, this was 1979, which is why the episode in which Blair develops a crush on a "retard" and tries to teach him to paint exists, but the irony is that Facts was considered progressive. One of the more consistent trajectory gags throughout the series involves the girls doling out clunky bon mots at the many male guest stars when they make a broadly sexist comment about women cooking or having babies. It's a nice assertion, but as the seasons progress, it's clear that the main social motivator for all of the central characters — even motorcycle-riding Jo (Nancy McKeon) when they run off to France for a fantastically awful TV movie adventure that's included with this box set — is finding a moderately attractive man with money to pay for the litter of kids they plan to have. Only Natalie (Mindy Cohn) stays somewhat free from this ideological trap — mainly, the show seems to imply, because she's fat and therefore unattractive (so she'll have to work). Despite this, even she concedes to this convention in later seasons.

Like most '80s television, the format is template-based didacticism, with an issue — racism, cheating on tests, drinking, and so on — being raised within the first couple of minutes in an episode only to come around to an overly simplified, moralistic observation by the 20-minute mark. In truth, it's painful to watch now, but at the time, it was funnier than much of the traditionalist twaddle flooding the airwaves.

From the perspective of cultural analysis, the series is a very fascinating watch in a modern context. The pseudo-progressive attitudes towards issues that they were still handling in a relatively offensive manner — Blair's differently abled "comedienne" cousin (Geri Jewell) routinely pops up and cracks jokes about her disposition (she suffers from muscular dystrophy) merely being a symptom of intoxication — is, in an overly sanitized, morally vain world, a nice guilty pleasure.

The box set includes some relatively new interview featurettes with the original season one cast of the show. The discussion is mostly about how the show came to be and why they completely retooled it for season two and axed two-thirds of the cast members (including a young and exceedingly awkward Molly Ringwald). Some of the actresses are bitter, while others acknowledge the experience for what it was. No one addresses the last few seasons, in which Mrs. Garrett opens a novelty shop and hires a sexy young construction worker in the form of George Clooney (who has a kick-ass mullet) to fix it up.