With a musical figure as universally known and analyzed as Michael Jackson – a scrutiny that has only intensified since his shocking death in 2009 – you'd be forgiven for thinking that no new light can be shed on the superstar artist's legacy. Spike Lee's exhaustive Bad 25 documentary, however, summarily lays waste to this line of thinking.

It isn't entirely surprising that Lee would eventually deliver an excellent music documentary. Music has always occupied an upfront prominence in his work and Lee documentaries 4 Little Girls and When the Levees Broke rank among his finest efforts. Lee's connection to this project is deepened by the fact that he collaborated with Jackson on two versions of the "They Don't Care About Us" video in 1996.

Based on a stunningly simple premise – focus strictly on Jackson's music – Lee's Bad 25 unearths Jackson's creative process on Bad, his follow-up to Thriller, the best-selling album of all time.

On the 25th anniversary of Bad's release, it's fair to say it was overshadowed by the gargantuan achievements of its predecessor – any record would have been – yet it is noteworthy for many reasons.

It's hard to argue with the main point that Lee makes: no African-American, or any other musical artist, for that matter, has ever wielded as much power in the music industry at the time of Bad's 1987 release. The film explores what Jackson does with this seemingly unfettered and unprecedented creative will.

Lee utilizes his impressive access to corral an enviable all-star guest list of talking heads to analyze Jackson's influence, importance and thematic goals as they proceed through the Bad album track by track.

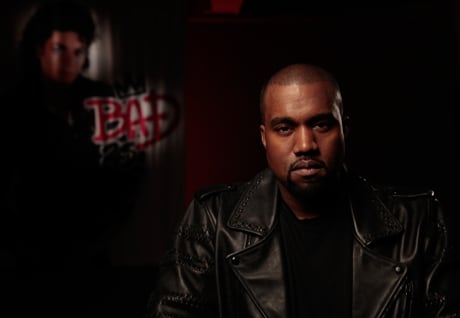

Artists such as Mariah Carey, Kanye West, ?uestlove, Justin Bieber and even Sheryl Crow (who was a backup vocalist on the Bad tour) show up to deferentially tip their hats, but the most revelatory insights come from those who collaborated closely with Jackson.

Jaw-dropping anecdotes and insights abound from collaborators such as choreographer Jeffrey Daniel, recording engineer Bruce Swedien and Bad short film director Martin Scorsese. The behind-the-scenes footage of Scorsese's Bad shoot, along with the interview with the legendary director, is fascinating. We also learn the identity of Annie, she of the infamous "Annie are you okay?" line in "Smooth Criminal," a story Lee's editing delivers with inimitable comic timing.

Lee's meticulous approach to historical research and unearthing archival footage is unabashedly rigorous, revelling in arcane recording techniques and details as much as broad brush strokes, like full concert performances of "Another Part of Me" and "Man in the Mirror," prompting you to watch and listen with fresh eyes and ears.

Such an approach leaves little room for negative critique – the only song to be summarily dismissed by cultural critics and session musicians alike is Stevie Wonder duet "Just Good Friends" – but Lee isn't interested in balancing that side of the equation, especially given the overwhelmingly disapproving media coverage Jackson's life often generated (explored in the film when discussing "Leave Me Alone").

Instead, Lee is successful in reminding us that Jackson was a very assertive artist with a relentless work ethic who took control over every aspect of his career and constantly challenged himself. This extended beyond his virtuosic singing, songwriting, production and musicianship in the recording studio to his choreography, image management and even his business investments, countering the "Wacko Jacko" image he constantly battled against.

And when Lee does briefly step outside of the focus on Bad to address Jackson's death, it's to underline the singular creative force he represented to his eclectic range of collaborators and, by extension, the world.

Of course, by then, as testament to Lee's authoritative and thoroughly entertaining work, you won't need to be convinced further of Jackson's musical legacy.

(40 Acres and a Mule)It isn't entirely surprising that Lee would eventually deliver an excellent music documentary. Music has always occupied an upfront prominence in his work and Lee documentaries 4 Little Girls and When the Levees Broke rank among his finest efforts. Lee's connection to this project is deepened by the fact that he collaborated with Jackson on two versions of the "They Don't Care About Us" video in 1996.

Based on a stunningly simple premise – focus strictly on Jackson's music – Lee's Bad 25 unearths Jackson's creative process on Bad, his follow-up to Thriller, the best-selling album of all time.

On the 25th anniversary of Bad's release, it's fair to say it was overshadowed by the gargantuan achievements of its predecessor – any record would have been – yet it is noteworthy for many reasons.

It's hard to argue with the main point that Lee makes: no African-American, or any other musical artist, for that matter, has ever wielded as much power in the music industry at the time of Bad's 1987 release. The film explores what Jackson does with this seemingly unfettered and unprecedented creative will.

Lee utilizes his impressive access to corral an enviable all-star guest list of talking heads to analyze Jackson's influence, importance and thematic goals as they proceed through the Bad album track by track.

Artists such as Mariah Carey, Kanye West, ?uestlove, Justin Bieber and even Sheryl Crow (who was a backup vocalist on the Bad tour) show up to deferentially tip their hats, but the most revelatory insights come from those who collaborated closely with Jackson.

Jaw-dropping anecdotes and insights abound from collaborators such as choreographer Jeffrey Daniel, recording engineer Bruce Swedien and Bad short film director Martin Scorsese. The behind-the-scenes footage of Scorsese's Bad shoot, along with the interview with the legendary director, is fascinating. We also learn the identity of Annie, she of the infamous "Annie are you okay?" line in "Smooth Criminal," a story Lee's editing delivers with inimitable comic timing.

Lee's meticulous approach to historical research and unearthing archival footage is unabashedly rigorous, revelling in arcane recording techniques and details as much as broad brush strokes, like full concert performances of "Another Part of Me" and "Man in the Mirror," prompting you to watch and listen with fresh eyes and ears.

Such an approach leaves little room for negative critique – the only song to be summarily dismissed by cultural critics and session musicians alike is Stevie Wonder duet "Just Good Friends" – but Lee isn't interested in balancing that side of the equation, especially given the overwhelmingly disapproving media coverage Jackson's life often generated (explored in the film when discussing "Leave Me Alone").

Instead, Lee is successful in reminding us that Jackson was a very assertive artist with a relentless work ethic who took control over every aspect of his career and constantly challenged himself. This extended beyond his virtuosic singing, songwriting, production and musicianship in the recording studio to his choreography, image management and even his business investments, countering the "Wacko Jacko" image he constantly battled against.

And when Lee does briefly step outside of the focus on Bad to address Jackson's death, it's to underline the singular creative force he represented to his eclectic range of collaborators and, by extension, the world.

Of course, by then, as testament to Lee's authoritative and thoroughly entertaining work, you won't need to be convinced further of Jackson's musical legacy.