You have to be a little bit crazy to want to become a stuntman in the movies, risking your life in the name of entertainment yet doubling an actor and never getting the deserved credit. But to be a stuntman in Asian cinema is equal to torture. Anyone familiar with international cinema will know Asian stuntmen are the most fearless and in Action Boys we get an intimate, firsthand, self-deprecating look into the weird and wonderful personalities of the Korean action film industry.

An especially droll Korean narrator introduces the characters to us during their audition process for the renowned Seoul Action School. Director Byung-Gil Jung is just one of 34 students who dream of success. While Jung doesn't have the physical talents of his peers, his passion is enough to get him accepted. Quickly he learns he just doesn't have the physical endurance to make it. But a number of his friends do: Gui-Duck becomes the most successful, rising through the ranks from stuntman to stunt coordinator faster than anyone; Sung-Li's good looks make him the ideal double for Asian stars like Tony Leung; Sung-Li's rock-hard abs are just one of the immense physical attributes that make him one of the most sought after stuntmen in Asia; and Sye-Jin, a dreamer like Jung, can't seem to do anything right except tattoo his entire back, as instructed by a fortune teller.

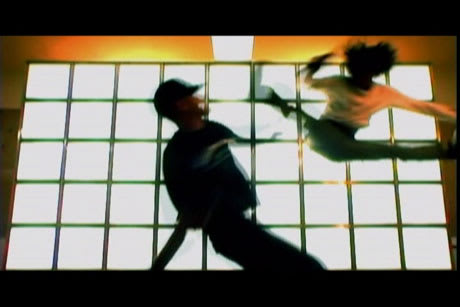

We get to see our "action boys" push their bodies to the limits on some of the highest profile films in Asian cinema (i.e., The Host, The Good, the Bad and the Weird). Most of the stunts are astonishing in their gustiness and reckless abandon. One of the most shocking is staged specifically for the documentary: we watch Gui-Duck walk across the street while talking to the camera, only to be hit by a car driving with blinding speed out of sight of the camera. With little effort Gui-Duck stands up and dusts himself off.

Producer Jennie Lee's omniscient voiceover directs the film, like the narrator in Amélie, consistently getting caught up in mundane, irrelevant details of the story. This provides an off-kilter sense of deadpan humour with elaborate detours into the stories of its characters. Unfortunately, at times, the style comes at the expense of narrative focus. In the opening act we're never really sure what the point of all this is, or who we're supposed to be following. And at 108 minutes, a 20-minute edit could have streamlined many of these obtuse detours.

But the film eventually gains a momentum of gleeful Asian energy and we develop a warm attachment to the characters. The most endearing moment comes when we meet Jin-Seock's young niece, who cries every time her uncle "dies" on screen. It's an impossibly cute moment that serves to highlight the dedication to their art and the risks and sacrifices they continually endure as a result.

An especially droll Korean narrator introduces the characters to us during their audition process for the renowned Seoul Action School. Director Byung-Gil Jung is just one of 34 students who dream of success. While Jung doesn't have the physical talents of his peers, his passion is enough to get him accepted. Quickly he learns he just doesn't have the physical endurance to make it. But a number of his friends do: Gui-Duck becomes the most successful, rising through the ranks from stuntman to stunt coordinator faster than anyone; Sung-Li's good looks make him the ideal double for Asian stars like Tony Leung; Sung-Li's rock-hard abs are just one of the immense physical attributes that make him one of the most sought after stuntmen in Asia; and Sye-Jin, a dreamer like Jung, can't seem to do anything right except tattoo his entire back, as instructed by a fortune teller.

We get to see our "action boys" push their bodies to the limits on some of the highest profile films in Asian cinema (i.e., The Host, The Good, the Bad and the Weird). Most of the stunts are astonishing in their gustiness and reckless abandon. One of the most shocking is staged specifically for the documentary: we watch Gui-Duck walk across the street while talking to the camera, only to be hit by a car driving with blinding speed out of sight of the camera. With little effort Gui-Duck stands up and dusts himself off.

Producer Jennie Lee's omniscient voiceover directs the film, like the narrator in Amélie, consistently getting caught up in mundane, irrelevant details of the story. This provides an off-kilter sense of deadpan humour with elaborate detours into the stories of its characters. Unfortunately, at times, the style comes at the expense of narrative focus. In the opening act we're never really sure what the point of all this is, or who we're supposed to be following. And at 108 minutes, a 20-minute edit could have streamlined many of these obtuse detours.

But the film eventually gains a momentum of gleeful Asian energy and we develop a warm attachment to the characters. The most endearing moment comes when we meet Jin-Seock's young niece, who cries every time her uncle "dies" on screen. It's an impossibly cute moment that serves to highlight the dedication to their art and the risks and sacrifices they continually endure as a result.