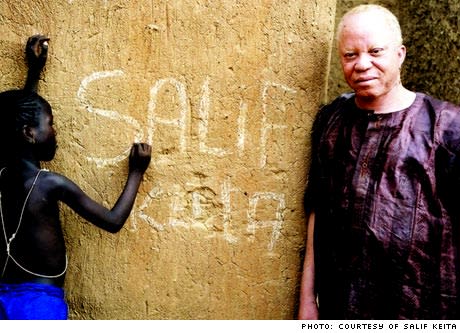

Salif Keita possesses one of the worlds unique voices powerful, sensitive, and blessed with a huge range; he draws from styles and forms of his Malian homeland, incorporating Islamic, soul, rock, French chanson, Spanish and Caribbean elements into his songs. His journey to international recognition has been just as unique. His life is defined by contrasts, and his mission is to fuse the disparate elements of his experience into a singular sensibility. He was born into Malian royalty but scorned as an outcast because of his albinism. He was one of the original "world music stars, at once an ambassador of African music but also aspiring to universal pop stardom. Trying to incorporate his many cultural influences over his nearly 40-year career, he has vacillated between astonishingly synthetic pop and post-modern African music. The dual forces of tradition and modernity, of his heritage and his journeys throughout the world continue to add to his musical vocabulary. At present, he is at the peak of his career, having released two widely acclaimed discs in a row and having finally reconciled his responsibilities and heritage in Mali with the demands of international recording and touring. This summer, he plays select high profile shows in Canada for the first time since the late 90s.

1200s

Sundiata Keita, the real life Lion King from whom Salif is directly descended, founds the Malian empire in the 13th century. At its height, this empire was the largest in Africa, as big as Europe. The central cities of the empire were located along the trade routes between North Africa, the Sahara desert and the sub-Saharan forest. Trade routes also stimulated cultural exchanges between the nomads of the Saharan desert and the more sedentary forest dwellers. A social order developed within the empire, with the Mandinkan Keita clan as its ruling family, and its history and culture to be disseminated by the griots. Griots were poets, musicians and advisers to the kings the yin to the political/warrior ruler yang. Outside of their specific status as oral historians, though, griots were essentially a lower caste. Roles were well defined; the deeds of kings and griots did not intermix. Nevertheless, the two functioned in symbiosis.

1949 to 1968

Mali is now a French colony. Keitas family are fairly well-to-do landowners who retain their noble caste. Salifou Keita is born August 25 1949, in Djoliba, a town in the south of Mali near the heartland of the old empire. His father had been informed by a "marabout (a West African Islamic scholar/mystic) that he would have a son destined for greatness, but only with great sacrifice. Keita is born albino, which shocks and scandalises his family. It is believed an albino baby, especially born of royalty, possesses dangerous, even demonic powers. Initially, Keitas father sends him and his mother away. Keitas mother has to hide him for fear of reprisals from superstitious mobs. After Keitas father receives council from a religious chief, Keita and his mother return to live an uneasy life on the familys farm. He works the fields, shouting and vocalising in order to chase away baboons and birds, before his father forces him to go to school. At first his appearance frightens his classmates; later he is simply shunned and ridiculed. His poor eyesight affects his ability to succeed in school, and Keita is thrown out.

Keita finds himself drawn to griots musicality, and the sounds emanating from the nearby Islamic school. His parents grow troubled over Keitas constant guitar playing around the house it breaks ancestral rules forbidding the performance of music by the royal family. His situation becomes increasingly desperate he cannot fulfil his familial expectations, he has not completed school and he is an outcast due to his skin colour. At the age of 20, he leaves home for Bamako, the capital of Mali. In an interview, he is terse about his early years: "I cried for 20 years. When I was thrown out of school I had no other solution [than to turn to music]. When I was 20 I accepted [my fate] and became resigned to it. He has said that he would have either have chosen music or petty crime, and music won out.

1969 to 1973

While in Bamako "I was living in the streets because I didnt know anyone in Bamako. I spent two years living in the market. He plays guitar and sings in bars and cafes. His soaring, powerful voice makes an impression on all who hear him. In 1970, a member of the Rail Band of Bamako, who play at the hotel restaurant at the railway station, spots Keita and invites him to audition. Salif isnt the first choice: "I went to a competition to become the lead singer of the Rail Band, and there were four candidates. I wasnt chosen, but the winner never came to rehearsal so they ended up with me. Typically in Bamako, hotels or wealthy individuals sponsor bands, providing instruments, accommodations and clothing. The Rail Band located at the only train station in Bamako is sponsored by the Malian government. Authorities insist their repertoire be composed of traditional Malian tunes. Nevertheless, the Rail Band revolutionise these traditional styles by setting them to electric instruments, and incorporating Afro-Cuban influences.

1973 to 1983

In 1973, Salif leaves the Rail Band to join Les Ambassadeurs, led by Guinean guitarist and singer Kanté Manfila. Manfila becomes a musical confidant, Keita tells Mondomix magazine: "Since I was not in a griot family, I was not allowed to learn traditional compositions. Kanté Manfila was my school. The bands headquarters are the Bamako Motel, where they play for a more international clientele. The band itself are multicultural, featuring Nigerian, Malian and Senegalese musicians and draw from a much wider palette of music. As the political situation in Mali becomes tenser, Keita and Manfila move to Abidjan, the capital of Cote DIvoire, which is more musically active and technically better equipped than Bamako. The group change their name to Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux.

In 1978, Keita enters a proper recording studio for the first time. The resulting album, Mandjou, is a huge success and showcases Les Ambassadeurs Internationauxs distinctiveness. His work at this time is documented on Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux featuring Salif Keita on U.S. folk/world label Rounder.

In December 1980, Keita and Manfila, financed by a Malian businessman, travel to Washington where they stay three months and record two albums, Primpin and Tounkan. These albums eventually show up on the Celluloid label several years later to little fanfare. Returning to Cote DIvoire, Manfila and Keita make another album, which is bootlegged until its official release as The Lost Album on Syllart in 2005. This album features some rough and ready studio craft, such as sped-up guitars, big reverb and a mixture of traditional and pop instrumentation. Fusion is inevitable, Keita tells Rootsworld magazine, and he embraces it: "You listen to people. You meet culture. You meet a lot of musicians and you listen to a lot of musicians who do all kinds of music. So it is only normal that you will change, you grow up and carry on until you die. Until the day you die, you are growing up and changing.

1984 to 1987

In 1983, Keita quits Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux, leaves Abidjan and returns to Bamako. His parents are aging, and Keita desires reconciliation with his family, who have softened their stance on his choice of profession. In 1984, he accepts a gig at the Musiques Metisses Festival in Angoulème, France (for "cross-breed music), where he is a sensation.

Following this concert, he moves to the Paris suburb of Montreuil, the home of some 15,000 Malians. The environment is very supportive for African musicians. He recalls, "At the time I arrived there was a policy to encourage African music and not to be subject to racism. Musicians like Mory Kante, Toure Kunda and Manu Dibango are recording in Paris, producing next-generation African records that incorporate musicians from many countries and much more studio polish than ever before. Pan-African musical styles emerge, which represent exciting new possibilities for international pop music. Yet Keita does not rush into a contract with labels that are piling on to the new marketing arena of "world music. He spends many years playing parties and traditional celebrations within the Malian community, acclimating himself to Paris. In 1985, Dibango, the elder statesman of African musicians in France, asks him to participate in recording the single "Tam Tam pour lEthiopie, French Africans counterpart to Band Aid.

After a six-year gap between albums, he releases Soro on Sterns Records in 1987. The record is produced by up and coming Senegalese producer Ibrahim Sylla, and arranged by French duo François Bréant and Jean-Philippe Rykiel. The result is an entirely new environment for Keitas soaring vocals. Partly traditional, especially in the vocal inflections and its fundamental rhythmic base, Soro takes many chances with big brass sections, expensive sounding synths, and overall pop sheen. The album sells 60,000 copies. Later this year, Keita is invited to England to participate in an all-star Afro-Anglo affair celebrating the still-jailed Nelson Mandelas 70th birthday. This event confirms his ascendancy to international world music stardom.

1988 to 1991

Island Records licenses Soro; it eventually sells more than 100,000 records worldwide. In 1989, he releases his second major label album, Ko-Yan. Glossy late 80s electronics encroach on more of the mix, complete with dreadful synth horn patches. His voice, in contrast with Soro, is more earthbound this time around. Perhaps this reflects the songs themes of the souring of the African experience in France, where the rise of the National Front, harassment and unemployment have become major problems.

1991 to 1993

Amen, produced by Weather Report main man Joe Zawinul and featuring Wayne Shorter and Carlos Santana, is released in 1991. Zawinul has a leaden touch with drum machines, but somehow Salifs voice is not as subsumed by the production as on his previous disc. This is his greatest bid for mainstream stardom yet, and the album is nominated for a Grammy. A world tour follows, which continues into 1993, including a special performance at Peter Gabriels WOMAD festival in England. He guests on the Cole Porter tribute Red Hot and Blue, radically revising "Begin the Beguine.

Later in 1991, his life story, Destiny Of A Noble Outcast, is documented by the BBC. Keita is filmed extensively in Mali, in his home village, the fields in which he learned to sing, and consorting with griots. The pain of his past and his present success are uncomfortably merged in the doc. His aged parents are featured prominently and appear to have reconciled (or resigned) themselves with their sons path.

1994 to 1999

Island puts out the retrospective Mansa of Mali collection, and Sonodisc releases 69-80, which documents his early years. Folon The Past is released in 1995 and sounds both more natural and more electronically sophisticated than his previous albums. Stylistically, more polyrhythms surface in his music, influenced by Antillean zouk and Afro-Cuban sources. As well, reggae and jazz figure more prominently in the cocktail of influences. Lyrically, as the title of the album suggests, he seems more drawn to Malian and African topics, reprising "Mandjou, and dedicating a song to Nelson Mandela.

Back in Mali, his father dies. By the end, Salif says, there has been a full reconciliation. Salif gives a concert in Bamako in December, and embarks on another international tour the following March. Increasingly, he is drawn back home when not touring. He takes up residence in Mali in 1996, and balances his time between Paris and Bamako.

Folons polar opposite, Sosie, comes out the following year. Sosie is a saccharine, adult contemporary treatment of classic French love songs, but its a repertoire he enjoys singing. One review characterises it thusly: "Fans of Gainsbourg wont get it. African music purists will hate it. Those with a taste for slightly confused and skewed pop music will love it. Island declines the disc, and it is released on the tiny Mellemfolkgleit label. When asked whether record labels have ever pressured him, he says confidently, "If a label gives me trouble, I just walk away.

The following year, he opens a recording studio in Bamako called Wanda Productions. Late in 1997, the first release in the Salif Keita Presents series appears: Ntin Naari by singer Fantani Touré. His next production is for Rokia Traoré, who has since become one of the brightest stars of Africa in recent years.

In 1999 he releases Papa on Blue Note subsidiary Metro Blue, produced by Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid. It is recorded in Bamako, Paris and New York although the material recorded in Bamako is completely unusable due to technical problems. Not surprisingly, there is a tougher, more rock-oriented sound to the album; never has the music been so ill-suited to his voice.

2000 to 2003

In 2000, he guests with Africando, the all-star African salsa band under the direction of Ibrahim Sylla. He is right at home on a Latinized version of his own "Ntoman, which sends a wake up call to fans around the world that hes still got it. In 2001 he opens a club in Bamako named Moffou, after a one-hole flute that he played as a child. The following year, switching labels to Universal, he releases the album Moffou. Synths and electronics are gone; few electric instruments are present on this album at all. The title song incorporates still more new influences, such as guest Cesaria Evoras Cape Verdean singing, but the array of hammered balafons, stringed instruments and percussion is marshalled by old hand Manfila into a densely textured sound that is Malian yet pan-African and Caribbean as well. Critics around the world hail it as a triumphant return to Salifs acoustic roots, when in fact this is only an exciting new phase in his relentless fusion of influences, albeit produced by acoustic ingredients. It ends up selling over 100,000 copies in France and 150,000 around the world. Keita is nominated for his second Grammy.

2004 to 2006

Mouffous futuristic yet traditional sound makes it something of a cult favourite among electronic producers. Following Martin Solveigs remix of "Madan, Universal releases Remixes from Mouffou featuring Osunlade, Doctor L and Frederic Galliano. Later in 2004, Salif decides to move back to Mali permanently. Upon his return, he organises three concerts in Bamako, and a special day of debate on the theme of "the development of the African music sector and its impact on the campaign against poverty, AIDS and other pandemics in Africa. His ability to mobilise and organise is recognised by the United Nations and in November, he is appointed UN Ambassador for Sport and Music.

He spends much of 2005 working on his next album in his studio, which has been rebuilt by Universal. Finally released at the end of 2005, Mbemba ("The Ancestor) is another career highlight. While preserving the acoustic focus of Mouffou, this album is both more intimate and more angular in its production. This is Keitas most successful fusion of technology and tradition to date. He has transformed the language of the acoustic sounds and rhythms of his homeland into a stimulating fusion for the most sophisticated ears. His vocals remain as clear and powerful as ever. Keita sounds like a man possessed by the spirits of his ancestors and ready to settle into this next phase of his life.

In Destiny Of A Noble Outcast Keita reflects on his heritage and his career trajectory "Im very happy I was born [in Mali], I accepted nature as it is, in the depths of its gentleness. I went elsewhere and I saw scientific life. I got to know other societies. Then I made a fusion and I saw that I was born where I should have been. There has never been one word to fully describe Keitas music; chances are there never will be.

The Essential Salif Keita

Soro (Sterns/Island, 1987)

Soro is an acquired taste. If you still have affection for Batman-era Prince keyboard sounds, youll get into this. For much of his career, Salifs music has been marked by adult contemporary pop influences, mostly by choice. This album presented him as an African pop star able to meld traditional instrumentation and rhythms with the heights of technological gloss. There is more than enough sensitivity in the arrangements, and sheer passion in Keitas voice to overcome the masses of guitars, backing vocals, drum machines and synths. There are plenty of atmospheric moments on this album the reverse of the bright and brassy soukous and zouk styles in vogue at the time.

Mouffou (Universal, 2002)

Much more than a man and a mic, it is a finely tuned mix of various hammered and plucked Malian instruments and with liberal sprinklings of electric and acoustic guitars. A few tracks absolutely throb with dance floor potential, but instead of having bass lines and kick drums, the required pulses are teased out of the lower frequencies of the instruments by compression and EQ. Dub influences abound, particularly on the faster selections like "Iniagige, where the stereo panning is simply mind-expanding. This is no mere use of acoustic instrumentation to suggest a sense of authenticity, Mouffou extends the possibilities of traditional instrumental sources made abstract by studio wizardry.

MBemba (Universal, 2005)

MBemba is another acoustic album sporting a rigorous mix, but it is even more successful. Lyrically, this is Keitas most historically themed disc, examining the history of Mali and his own obligations to the country. Up to five acoustic guitars intertwine with percussion, and the judicious arrangement of bass frequencies is a labyrinth of polyrhythmic activity. The album really takes off in "Laban where the serene groove changes midway to a reverbed electric Afro-rumba groove wherein Salifs vocals take off to ecstatic heights unheard of on any of his albums to date. "Yambo boasts a mix that conjures Richie Hawtins tightly controlled rhythmic variations in a more exuberant context. This disc is a triumph of concept and execution, and is profoundly soulful.

1200s

Sundiata Keita, the real life Lion King from whom Salif is directly descended, founds the Malian empire in the 13th century. At its height, this empire was the largest in Africa, as big as Europe. The central cities of the empire were located along the trade routes between North Africa, the Sahara desert and the sub-Saharan forest. Trade routes also stimulated cultural exchanges between the nomads of the Saharan desert and the more sedentary forest dwellers. A social order developed within the empire, with the Mandinkan Keita clan as its ruling family, and its history and culture to be disseminated by the griots. Griots were poets, musicians and advisers to the kings the yin to the political/warrior ruler yang. Outside of their specific status as oral historians, though, griots were essentially a lower caste. Roles were well defined; the deeds of kings and griots did not intermix. Nevertheless, the two functioned in symbiosis.

1949 to 1968

Mali is now a French colony. Keitas family are fairly well-to-do landowners who retain their noble caste. Salifou Keita is born August 25 1949, in Djoliba, a town in the south of Mali near the heartland of the old empire. His father had been informed by a "marabout (a West African Islamic scholar/mystic) that he would have a son destined for greatness, but only with great sacrifice. Keita is born albino, which shocks and scandalises his family. It is believed an albino baby, especially born of royalty, possesses dangerous, even demonic powers. Initially, Keitas father sends him and his mother away. Keitas mother has to hide him for fear of reprisals from superstitious mobs. After Keitas father receives council from a religious chief, Keita and his mother return to live an uneasy life on the familys farm. He works the fields, shouting and vocalising in order to chase away baboons and birds, before his father forces him to go to school. At first his appearance frightens his classmates; later he is simply shunned and ridiculed. His poor eyesight affects his ability to succeed in school, and Keita is thrown out.

Keita finds himself drawn to griots musicality, and the sounds emanating from the nearby Islamic school. His parents grow troubled over Keitas constant guitar playing around the house it breaks ancestral rules forbidding the performance of music by the royal family. His situation becomes increasingly desperate he cannot fulfil his familial expectations, he has not completed school and he is an outcast due to his skin colour. At the age of 20, he leaves home for Bamako, the capital of Mali. In an interview, he is terse about his early years: "I cried for 20 years. When I was thrown out of school I had no other solution [than to turn to music]. When I was 20 I accepted [my fate] and became resigned to it. He has said that he would have either have chosen music or petty crime, and music won out.

1969 to 1973

While in Bamako "I was living in the streets because I didnt know anyone in Bamako. I spent two years living in the market. He plays guitar and sings in bars and cafes. His soaring, powerful voice makes an impression on all who hear him. In 1970, a member of the Rail Band of Bamako, who play at the hotel restaurant at the railway station, spots Keita and invites him to audition. Salif isnt the first choice: "I went to a competition to become the lead singer of the Rail Band, and there were four candidates. I wasnt chosen, but the winner never came to rehearsal so they ended up with me. Typically in Bamako, hotels or wealthy individuals sponsor bands, providing instruments, accommodations and clothing. The Rail Band located at the only train station in Bamako is sponsored by the Malian government. Authorities insist their repertoire be composed of traditional Malian tunes. Nevertheless, the Rail Band revolutionise these traditional styles by setting them to electric instruments, and incorporating Afro-Cuban influences.

1973 to 1983

In 1973, Salif leaves the Rail Band to join Les Ambassadeurs, led by Guinean guitarist and singer Kanté Manfila. Manfila becomes a musical confidant, Keita tells Mondomix magazine: "Since I was not in a griot family, I was not allowed to learn traditional compositions. Kanté Manfila was my school. The bands headquarters are the Bamako Motel, where they play for a more international clientele. The band itself are multicultural, featuring Nigerian, Malian and Senegalese musicians and draw from a much wider palette of music. As the political situation in Mali becomes tenser, Keita and Manfila move to Abidjan, the capital of Cote DIvoire, which is more musically active and technically better equipped than Bamako. The group change their name to Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux.

In 1978, Keita enters a proper recording studio for the first time. The resulting album, Mandjou, is a huge success and showcases Les Ambassadeurs Internationauxs distinctiveness. His work at this time is documented on Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux featuring Salif Keita on U.S. folk/world label Rounder.

In December 1980, Keita and Manfila, financed by a Malian businessman, travel to Washington where they stay three months and record two albums, Primpin and Tounkan. These albums eventually show up on the Celluloid label several years later to little fanfare. Returning to Cote DIvoire, Manfila and Keita make another album, which is bootlegged until its official release as The Lost Album on Syllart in 2005. This album features some rough and ready studio craft, such as sped-up guitars, big reverb and a mixture of traditional and pop instrumentation. Fusion is inevitable, Keita tells Rootsworld magazine, and he embraces it: "You listen to people. You meet culture. You meet a lot of musicians and you listen to a lot of musicians who do all kinds of music. So it is only normal that you will change, you grow up and carry on until you die. Until the day you die, you are growing up and changing.

1984 to 1987

In 1983, Keita quits Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux, leaves Abidjan and returns to Bamako. His parents are aging, and Keita desires reconciliation with his family, who have softened their stance on his choice of profession. In 1984, he accepts a gig at the Musiques Metisses Festival in Angoulème, France (for "cross-breed music), where he is a sensation.

Following this concert, he moves to the Paris suburb of Montreuil, the home of some 15,000 Malians. The environment is very supportive for African musicians. He recalls, "At the time I arrived there was a policy to encourage African music and not to be subject to racism. Musicians like Mory Kante, Toure Kunda and Manu Dibango are recording in Paris, producing next-generation African records that incorporate musicians from many countries and much more studio polish than ever before. Pan-African musical styles emerge, which represent exciting new possibilities for international pop music. Yet Keita does not rush into a contract with labels that are piling on to the new marketing arena of "world music. He spends many years playing parties and traditional celebrations within the Malian community, acclimating himself to Paris. In 1985, Dibango, the elder statesman of African musicians in France, asks him to participate in recording the single "Tam Tam pour lEthiopie, French Africans counterpart to Band Aid.

After a six-year gap between albums, he releases Soro on Sterns Records in 1987. The record is produced by up and coming Senegalese producer Ibrahim Sylla, and arranged by French duo François Bréant and Jean-Philippe Rykiel. The result is an entirely new environment for Keitas soaring vocals. Partly traditional, especially in the vocal inflections and its fundamental rhythmic base, Soro takes many chances with big brass sections, expensive sounding synths, and overall pop sheen. The album sells 60,000 copies. Later this year, Keita is invited to England to participate in an all-star Afro-Anglo affair celebrating the still-jailed Nelson Mandelas 70th birthday. This event confirms his ascendancy to international world music stardom.

1988 to 1991

Island Records licenses Soro; it eventually sells more than 100,000 records worldwide. In 1989, he releases his second major label album, Ko-Yan. Glossy late 80s electronics encroach on more of the mix, complete with dreadful synth horn patches. His voice, in contrast with Soro, is more earthbound this time around. Perhaps this reflects the songs themes of the souring of the African experience in France, where the rise of the National Front, harassment and unemployment have become major problems.

1991 to 1993

Amen, produced by Weather Report main man Joe Zawinul and featuring Wayne Shorter and Carlos Santana, is released in 1991. Zawinul has a leaden touch with drum machines, but somehow Salifs voice is not as subsumed by the production as on his previous disc. This is his greatest bid for mainstream stardom yet, and the album is nominated for a Grammy. A world tour follows, which continues into 1993, including a special performance at Peter Gabriels WOMAD festival in England. He guests on the Cole Porter tribute Red Hot and Blue, radically revising "Begin the Beguine.

Later in 1991, his life story, Destiny Of A Noble Outcast, is documented by the BBC. Keita is filmed extensively in Mali, in his home village, the fields in which he learned to sing, and consorting with griots. The pain of his past and his present success are uncomfortably merged in the doc. His aged parents are featured prominently and appear to have reconciled (or resigned) themselves with their sons path.

1994 to 1999

Island puts out the retrospective Mansa of Mali collection, and Sonodisc releases 69-80, which documents his early years. Folon The Past is released in 1995 and sounds both more natural and more electronically sophisticated than his previous albums. Stylistically, more polyrhythms surface in his music, influenced by Antillean zouk and Afro-Cuban sources. As well, reggae and jazz figure more prominently in the cocktail of influences. Lyrically, as the title of the album suggests, he seems more drawn to Malian and African topics, reprising "Mandjou, and dedicating a song to Nelson Mandela.

Back in Mali, his father dies. By the end, Salif says, there has been a full reconciliation. Salif gives a concert in Bamako in December, and embarks on another international tour the following March. Increasingly, he is drawn back home when not touring. He takes up residence in Mali in 1996, and balances his time between Paris and Bamako.

Folons polar opposite, Sosie, comes out the following year. Sosie is a saccharine, adult contemporary treatment of classic French love songs, but its a repertoire he enjoys singing. One review characterises it thusly: "Fans of Gainsbourg wont get it. African music purists will hate it. Those with a taste for slightly confused and skewed pop music will love it. Island declines the disc, and it is released on the tiny Mellemfolkgleit label. When asked whether record labels have ever pressured him, he says confidently, "If a label gives me trouble, I just walk away.

The following year, he opens a recording studio in Bamako called Wanda Productions. Late in 1997, the first release in the Salif Keita Presents series appears: Ntin Naari by singer Fantani Touré. His next production is for Rokia Traoré, who has since become one of the brightest stars of Africa in recent years.

In 1999 he releases Papa on Blue Note subsidiary Metro Blue, produced by Living Colour guitarist Vernon Reid. It is recorded in Bamako, Paris and New York although the material recorded in Bamako is completely unusable due to technical problems. Not surprisingly, there is a tougher, more rock-oriented sound to the album; never has the music been so ill-suited to his voice.

2000 to 2003

In 2000, he guests with Africando, the all-star African salsa band under the direction of Ibrahim Sylla. He is right at home on a Latinized version of his own "Ntoman, which sends a wake up call to fans around the world that hes still got it. In 2001 he opens a club in Bamako named Moffou, after a one-hole flute that he played as a child. The following year, switching labels to Universal, he releases the album Moffou. Synths and electronics are gone; few electric instruments are present on this album at all. The title song incorporates still more new influences, such as guest Cesaria Evoras Cape Verdean singing, but the array of hammered balafons, stringed instruments and percussion is marshalled by old hand Manfila into a densely textured sound that is Malian yet pan-African and Caribbean as well. Critics around the world hail it as a triumphant return to Salifs acoustic roots, when in fact this is only an exciting new phase in his relentless fusion of influences, albeit produced by acoustic ingredients. It ends up selling over 100,000 copies in France and 150,000 around the world. Keita is nominated for his second Grammy.

2004 to 2006

Mouffous futuristic yet traditional sound makes it something of a cult favourite among electronic producers. Following Martin Solveigs remix of "Madan, Universal releases Remixes from Mouffou featuring Osunlade, Doctor L and Frederic Galliano. Later in 2004, Salif decides to move back to Mali permanently. Upon his return, he organises three concerts in Bamako, and a special day of debate on the theme of "the development of the African music sector and its impact on the campaign against poverty, AIDS and other pandemics in Africa. His ability to mobilise and organise is recognised by the United Nations and in November, he is appointed UN Ambassador for Sport and Music.

He spends much of 2005 working on his next album in his studio, which has been rebuilt by Universal. Finally released at the end of 2005, Mbemba ("The Ancestor) is another career highlight. While preserving the acoustic focus of Mouffou, this album is both more intimate and more angular in its production. This is Keitas most successful fusion of technology and tradition to date. He has transformed the language of the acoustic sounds and rhythms of his homeland into a stimulating fusion for the most sophisticated ears. His vocals remain as clear and powerful as ever. Keita sounds like a man possessed by the spirits of his ancestors and ready to settle into this next phase of his life.

In Destiny Of A Noble Outcast Keita reflects on his heritage and his career trajectory "Im very happy I was born [in Mali], I accepted nature as it is, in the depths of its gentleness. I went elsewhere and I saw scientific life. I got to know other societies. Then I made a fusion and I saw that I was born where I should have been. There has never been one word to fully describe Keitas music; chances are there never will be.

The Essential Salif Keita

Soro (Sterns/Island, 1987)

Soro is an acquired taste. If you still have affection for Batman-era Prince keyboard sounds, youll get into this. For much of his career, Salifs music has been marked by adult contemporary pop influences, mostly by choice. This album presented him as an African pop star able to meld traditional instrumentation and rhythms with the heights of technological gloss. There is more than enough sensitivity in the arrangements, and sheer passion in Keitas voice to overcome the masses of guitars, backing vocals, drum machines and synths. There are plenty of atmospheric moments on this album the reverse of the bright and brassy soukous and zouk styles in vogue at the time.

Mouffou (Universal, 2002)

Much more than a man and a mic, it is a finely tuned mix of various hammered and plucked Malian instruments and with liberal sprinklings of electric and acoustic guitars. A few tracks absolutely throb with dance floor potential, but instead of having bass lines and kick drums, the required pulses are teased out of the lower frequencies of the instruments by compression and EQ. Dub influences abound, particularly on the faster selections like "Iniagige, where the stereo panning is simply mind-expanding. This is no mere use of acoustic instrumentation to suggest a sense of authenticity, Mouffou extends the possibilities of traditional instrumental sources made abstract by studio wizardry.

MBemba (Universal, 2005)

MBemba is another acoustic album sporting a rigorous mix, but it is even more successful. Lyrically, this is Keitas most historically themed disc, examining the history of Mali and his own obligations to the country. Up to five acoustic guitars intertwine with percussion, and the judicious arrangement of bass frequencies is a labyrinth of polyrhythmic activity. The album really takes off in "Laban where the serene groove changes midway to a reverbed electric Afro-rumba groove wherein Salifs vocals take off to ecstatic heights unheard of on any of his albums to date. "Yambo boasts a mix that conjures Richie Hawtins tightly controlled rhythmic variations in a more exuberant context. This disc is a triumph of concept and execution, and is profoundly soulful.