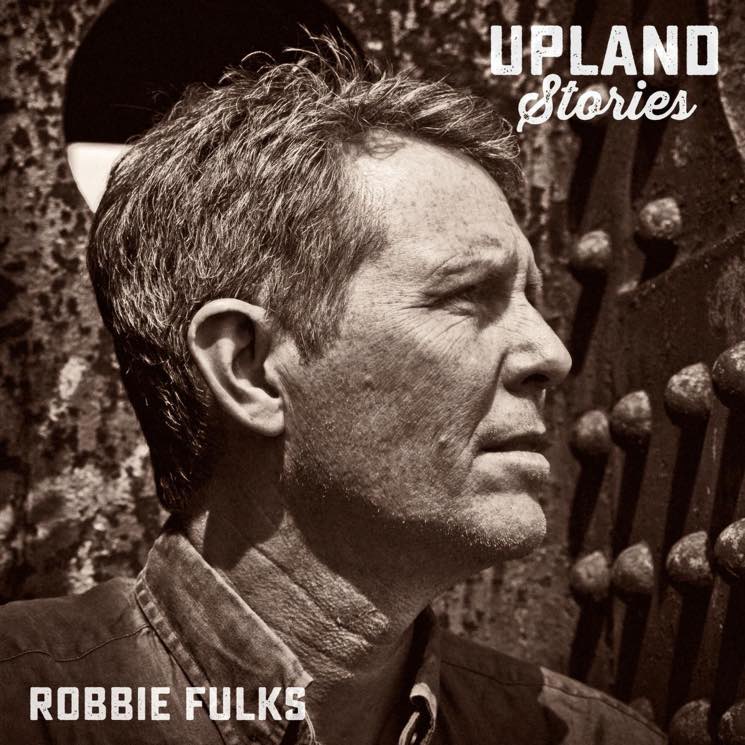

Chicago-based songwriter Robbie Fulks enters into Upland Stories, his 12th album) via the descriptive, late-night ruminations of James Agee, whose 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men — about a 1936 trip with photographer Walker Evans documenting poverty in the South — inspired three of the songs on the new album: opener "Alabama At Night," sparse banjo and fiddle tune "America Is A Hard Religion" and atmospheric, poetic "A Miracle." All three are showstoppers, if slightly awkward ones, thanks to verbose and archaic, hard-working language.

What's impressive is how well integrated these Agee-inspired tunes are with their more modern cousins, including a wonderfully fresh cover of Merle Kilgore's nostalgic "Baby Rocked Her Dolly," which, considering Frankie Miller recorded it in 1959, acts as a bridge between the eras traversed on the album, from the 1930s to the 1970s, and on to the present.

Like Agee, Fulks grew up in the South (in "upland" Virginia and North Carolina) and like Agee, Fulks writes about Southern-ness. On noirish alt-country rambler "Never Come Home" (which moves at the pace of a slow Neil Young ballad and would make a good Drive-By Truckers song), Fulks croons over creeping organ in such a low, hushed tone he almost sounds like a different singer, while on the lighter, wistful folk blues of "Sarah Jane," (backed just by lovely guitar from Fulks and baritone electric by Robbie Gjersoe), Fulks displays typically dry humour: "I was young in Charlottesville / That was a long long time / Now I'm homesick and I'm poor; poor is at least no crime."

Fulks also writes (quite movingly) about home and family, love and adulthood from the perspective of a man old enough to have children embarking on their own adulthoods. Country ballad "Needed," in which Fulks talks to his (imaginary) 18-year-old daughter about the nature of love and his own spotted history, about getting a girlfriend pregnant and implying she ended up having an abortion, is the most profoundly personal example; I cried first time I heard it.

Elsewhere, Fulks' songwriting has more levity: "Aunt Peg's New Old Man" is about a family member's golden years romance with a side of bluegrass nerdery about Scruggs-style banjo-playing (Fulks plays a little banjo on a record here for the first time), while on "Katy Kay," Fulks laughs out loud in response to a resonator guitar line. The song sounds as traditional as they come, though Fulks wrote it, and if those lyrics weren't mitigated by laughter, they'd just be awful. (The whole album was recorded, mostly live, by longtime collaborator Steve Albini.)

Though Upland Stories encompasses various moods and genres ("Sweet As Sweet Comes" hangs out near the end as a standalone, slightly cheeseball, soul-folk love song) the one that lingers is the unhurried, sepia-toned feel of expansive closer "Fare Thee Well, Carolina Girls" and the gently spacious "South Bend Soldiers On." It's on songs like these that Fulks' lyrics are at their most beautiful and poetic.

(Bloodshot)What's impressive is how well integrated these Agee-inspired tunes are with their more modern cousins, including a wonderfully fresh cover of Merle Kilgore's nostalgic "Baby Rocked Her Dolly," which, considering Frankie Miller recorded it in 1959, acts as a bridge between the eras traversed on the album, from the 1930s to the 1970s, and on to the present.

Like Agee, Fulks grew up in the South (in "upland" Virginia and North Carolina) and like Agee, Fulks writes about Southern-ness. On noirish alt-country rambler "Never Come Home" (which moves at the pace of a slow Neil Young ballad and would make a good Drive-By Truckers song), Fulks croons over creeping organ in such a low, hushed tone he almost sounds like a different singer, while on the lighter, wistful folk blues of "Sarah Jane," (backed just by lovely guitar from Fulks and baritone electric by Robbie Gjersoe), Fulks displays typically dry humour: "I was young in Charlottesville / That was a long long time / Now I'm homesick and I'm poor; poor is at least no crime."

Fulks also writes (quite movingly) about home and family, love and adulthood from the perspective of a man old enough to have children embarking on their own adulthoods. Country ballad "Needed," in which Fulks talks to his (imaginary) 18-year-old daughter about the nature of love and his own spotted history, about getting a girlfriend pregnant and implying she ended up having an abortion, is the most profoundly personal example; I cried first time I heard it.

Elsewhere, Fulks' songwriting has more levity: "Aunt Peg's New Old Man" is about a family member's golden years romance with a side of bluegrass nerdery about Scruggs-style banjo-playing (Fulks plays a little banjo on a record here for the first time), while on "Katy Kay," Fulks laughs out loud in response to a resonator guitar line. The song sounds as traditional as they come, though Fulks wrote it, and if those lyrics weren't mitigated by laughter, they'd just be awful. (The whole album was recorded, mostly live, by longtime collaborator Steve Albini.)

Though Upland Stories encompasses various moods and genres ("Sweet As Sweet Comes" hangs out near the end as a standalone, slightly cheeseball, soul-folk love song) the one that lingers is the unhurried, sepia-toned feel of expansive closer "Fare Thee Well, Carolina Girls" and the gently spacious "South Bend Soldiers On." It's on songs like these that Fulks' lyrics are at their most beautiful and poetic.