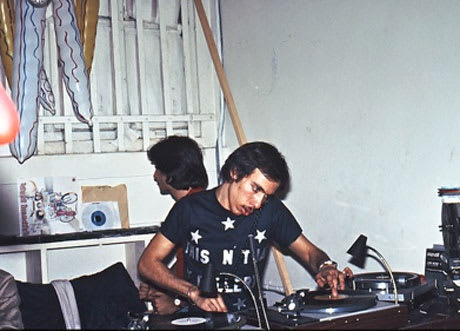

Nicky Siano is unquestionably one of the godfathers of dance music. Taking the house party-cum-eco-system of David Mancuso's Loft — as well as the technical innovations of New York spinners like Francis Grasso and Michael Cappello — to frenzied new levels, Siano's storied club the Gallery (where the late Frankie Knuckles, and Larry Levan inaugurated their club careers) was the template for later, legendary nightspots, the Paradise Garage and the Warehouse. Siano has just released Love Is The Message, a two-disc DVD shot at the Gallery in 1977 that offers an intimate look into the New York dance music underground. Speaking by phone from his home in New York, Siano spoke about the film, his DJ style and his memories of the era's dance music scene.

How did the film come about and why did it take so long for the footage to see the light of day?

It was a very expensive process. My cousin who had spearheaded the whole project just lost money and he couldn't spend any money. I went to him and I said, "Hey do you still have that footage?" and he said "Yes, I sure do." We digitized it all (another $20,000).We were in the whole about $50, $60 grand. We figured that this was such great footage and we'll get an editor and we'll have a movie. So I got an editor who was reasonable enough, just 40 bucks an hour, to work with me and we sat down for another $10 grand of editing sessions. We got it edited and it was ready to be released. We took it to some of the people who owned the rights to some of the songs that we wanted to use, and they said "Sure, we'll give them to you for $50,000" and we didn't have it. So I went back into the recording studio and I recreated the four songs that I couldn't get from the people and that took another year and another couple grand, and here we are.

How would you describe your DJ Style? How did you build on the foundation laid by David Mancuso, Francis Grasso and Michael Cappello?

Everybody was into this blending. Everybody called it blending. The blend had to be right. It was all this kind of serial thing that was about timing — sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn't. So I started the mats and flip-queuing, which they weren't doing. They were doing like timing; they would time it out and touch the record to slow it down or speed it up. But I really perfected that. I think that I'm an excitement junkie. When I peak the crowd, I would peak them to the nth degree. I would just keep peaking them until finally I felt that I would rest. [laughs] I feel like I peaked the crowd more and I did more about creating an atmosphere — the lighting, the sound, the way the room was set up and the way that everything worked in the room. I controlled it all from the DJ booth and when I walked into the Gallery and I saw those 30 foot ceilings, I had this idea of hanging the lights on three levels and my brother made it happen with his engineering degree and it became Studio 54's light show. [Studio 54 co-founder] Steve Rubell used to sit under the booth at the Gallery and watched that light show going up into the ceiling. I really think that some of the ideas were taken out from that.

One thing that I thought that was really poignant while watching the film were the testimonials by some of the members. How did you foster that sense of community?

At the time, there were rules [people of the same sex couldn't dance with each other] and we didn't make that up for the film. They were enforced. We started to deal with the same people week after week after week. We encouraged that and people started bonding and becoming friends. The thing that made that happen was the private membership, but I call it private invitations, and that made that community happen because no one could just walk in the door. You had to be with a member or you had to be a member. The private invitation system really fostered that sense of community and we did that at the club. I would have "Land Of Make Believe" [by Chuck Mangione and Esther Satterfield] playing for 14 or 15 minutes and I would go around to the people gathered around the dance floor and to the side and I would say, "Hi, good evening. You want a little tab of acid?" I would interact with people in the booth all of the time. After it would close, I would sit around with people and talk and make jokes. So people felt they were coming to a party at someone's house, not a club. And that's what I wanted.

Would you say that personal liberation was your goal as a DJ?

I was so young when all that was happening. What I felt was that the environment created a space for people wanting to party the way that they did. It was a celebration of all that we had accomplished. The words to the music, I mean, one of the first songs that I became identified with was "Love Epidemic" [by The Trammps]. The words to it:" spread the love epidemic all around the world, to every girl, sister, man woman and child." It was just that atmosphere. We had stopped the war. "What's Going On," by Marvin Gaye and all the other records were questioning our integrity, our ability, our range of ability. How far could we go? If we stopped the war, could we change the world? Unfortunately, the whole scene took on a sex, drugs and rock'n'roll thing and that's where the turn was totally split from the Gallery to what Studio 54 was. Yes, there were drugs at the Gallery and yes, people hooked up once in a while but that wasn't why they were there. They were there to celebrate their life and freedom, whereas when they got to Studio 54 they were there to be seen, do drugs and fuck. It was no longer people thinking, "How far could we take this? Can we get someone elected mayor?" We were in a position to get people elected but we turned around and partied. We took it the wrong way. Every little piece of music was about our empowerment.

What was your criteria in selecting music?

The criteria was very personal and it had to move me. I guess I wasn't off that much. "Turn The Beat Around," "Love Is The Message," "Love Hangover," "Rock Me Baby," "Rock The Boat," "Soul Makossa." The list is endless that I picked.

What would you like younger viewers to take from watching the film?

I'd like younger people, especially those in the industry, to see how it was. Look how people partied and why not try and create environments that foster that kind of feeling instead of "buy a bottle!" [or] "Do you want a table or do you want to stand?"

Why do you think that's not happening now?

Because of the talent is left outside of the decision making process of how to build the club, how to make the sound, how to make the room more inviting. The talent is the last thing added to the mix when everything is said and done by people who are mostly rich people who want to make more money. People who have no talent, no eye or no vision. What do they do? They copy what's the latest thing. And they copy and try to make it a bit better. And surely, that's what we did back then too, but I'm talking about leaps that we would make. Our motivation was we wanted to throw a fierce party.

How did the film come about and why did it take so long for the footage to see the light of day?

It was a very expensive process. My cousin who had spearheaded the whole project just lost money and he couldn't spend any money. I went to him and I said, "Hey do you still have that footage?" and he said "Yes, I sure do." We digitized it all (another $20,000).We were in the whole about $50, $60 grand. We figured that this was such great footage and we'll get an editor and we'll have a movie. So I got an editor who was reasonable enough, just 40 bucks an hour, to work with me and we sat down for another $10 grand of editing sessions. We got it edited and it was ready to be released. We took it to some of the people who owned the rights to some of the songs that we wanted to use, and they said "Sure, we'll give them to you for $50,000" and we didn't have it. So I went back into the recording studio and I recreated the four songs that I couldn't get from the people and that took another year and another couple grand, and here we are.

How would you describe your DJ Style? How did you build on the foundation laid by David Mancuso, Francis Grasso and Michael Cappello?

Everybody was into this blending. Everybody called it blending. The blend had to be right. It was all this kind of serial thing that was about timing — sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn't. So I started the mats and flip-queuing, which they weren't doing. They were doing like timing; they would time it out and touch the record to slow it down or speed it up. But I really perfected that. I think that I'm an excitement junkie. When I peak the crowd, I would peak them to the nth degree. I would just keep peaking them until finally I felt that I would rest. [laughs] I feel like I peaked the crowd more and I did more about creating an atmosphere — the lighting, the sound, the way the room was set up and the way that everything worked in the room. I controlled it all from the DJ booth and when I walked into the Gallery and I saw those 30 foot ceilings, I had this idea of hanging the lights on three levels and my brother made it happen with his engineering degree and it became Studio 54's light show. [Studio 54 co-founder] Steve Rubell used to sit under the booth at the Gallery and watched that light show going up into the ceiling. I really think that some of the ideas were taken out from that.

One thing that I thought that was really poignant while watching the film were the testimonials by some of the members. How did you foster that sense of community?

At the time, there were rules [people of the same sex couldn't dance with each other] and we didn't make that up for the film. They were enforced. We started to deal with the same people week after week after week. We encouraged that and people started bonding and becoming friends. The thing that made that happen was the private membership, but I call it private invitations, and that made that community happen because no one could just walk in the door. You had to be with a member or you had to be a member. The private invitation system really fostered that sense of community and we did that at the club. I would have "Land Of Make Believe" [by Chuck Mangione and Esther Satterfield] playing for 14 or 15 minutes and I would go around to the people gathered around the dance floor and to the side and I would say, "Hi, good evening. You want a little tab of acid?" I would interact with people in the booth all of the time. After it would close, I would sit around with people and talk and make jokes. So people felt they were coming to a party at someone's house, not a club. And that's what I wanted.

Would you say that personal liberation was your goal as a DJ?

I was so young when all that was happening. What I felt was that the environment created a space for people wanting to party the way that they did. It was a celebration of all that we had accomplished. The words to the music, I mean, one of the first songs that I became identified with was "Love Epidemic" [by The Trammps]. The words to it:" spread the love epidemic all around the world, to every girl, sister, man woman and child." It was just that atmosphere. We had stopped the war. "What's Going On," by Marvin Gaye and all the other records were questioning our integrity, our ability, our range of ability. How far could we go? If we stopped the war, could we change the world? Unfortunately, the whole scene took on a sex, drugs and rock'n'roll thing and that's where the turn was totally split from the Gallery to what Studio 54 was. Yes, there were drugs at the Gallery and yes, people hooked up once in a while but that wasn't why they were there. They were there to celebrate their life and freedom, whereas when they got to Studio 54 they were there to be seen, do drugs and fuck. It was no longer people thinking, "How far could we take this? Can we get someone elected mayor?" We were in a position to get people elected but we turned around and partied. We took it the wrong way. Every little piece of music was about our empowerment.

What was your criteria in selecting music?

The criteria was very personal and it had to move me. I guess I wasn't off that much. "Turn The Beat Around," "Love Is The Message," "Love Hangover," "Rock Me Baby," "Rock The Boat," "Soul Makossa." The list is endless that I picked.

What would you like younger viewers to take from watching the film?

I'd like younger people, especially those in the industry, to see how it was. Look how people partied and why not try and create environments that foster that kind of feeling instead of "buy a bottle!" [or] "Do you want a table or do you want to stand?"

Why do you think that's not happening now?

Because of the talent is left outside of the decision making process of how to build the club, how to make the sound, how to make the room more inviting. The talent is the last thing added to the mix when everything is said and done by people who are mostly rich people who want to make more money. People who have no talent, no eye or no vision. What do they do? They copy what's the latest thing. And they copy and try to make it a bit better. And surely, that's what we did back then too, but I'm talking about leaps that we would make. Our motivation was we wanted to throw a fierce party.