Down a dead-end street, a stone's throw from Ottawa's Italian district, you'll find Dave Draves milling about in the cosy confines of Little Bullhorn. He's had lots of time for reflection over the past few months, having just celebrated ten years of recording, and his 40th birthday.

Originally built as a practice space to accommodate his group Fishtales and other friends' bands, it wasn't long before Draves tried his hand at recording. "I was motivated by the fact that I liked the Wooden Stars," he says with a smile. "I just had to record them, so I rented a Fostex and we got to work one night. I had no gear and no way to monitor what we were recording, and when we listened back to the tape the next day there was nothing on it."

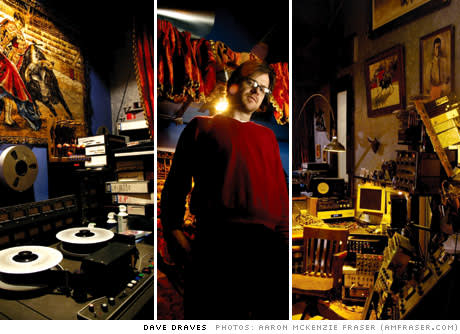

From these humble beginnings, Draves began to build Little Bullhorn, reading his share of Tape Op magazines along the way. He spent most of his free time seeking and acquiring vintage tube and analog gear, as well as a plethora of matador-themed décor from thrift stores. Over the years, Draves' connections and Pennysaver purchases have provided him with a collection of toys that would make any music geek jealous. Among the treasures are his two optigans, an egg-shaped chair with built-in speakers, and a steel plate reverb originally used in Montreal's RCA Victor studio. "I've always tried to reinvest money in the studio, as opposed to borrowing from the bank. I was inspired when I visited Chemical Sound [in Toronto] while the Wooden Stars were making their second record; they had quite a collection of interesting, vintage gear. It's neat to get all these old things and have them available during the creative process. It allows you to be spontaneous and create an environment where good things can happen."

One would argue that it's this philosophy that makes Draves' Little Bullhorn stand out from the pack, and drawn recent out-of-town clients like Howe Gelb. "My approach to recording is to make the studio as transparent as possible, and the process as un-intimidating as possible. I don't want the studio to have a bigger importance than the players. I think the tendency when bands are recording is to over-fix their mistakes. I would much rather allow for things to have an energy behind them, rather than be perfect."

The look and feel of the studio reflects this attitude. Cluttered with cables, lamps, and musical trinkets of all kinds, Little Bullhorn is a far cry from the sterile environment of a traditional recording studio. He admits that it's not for everyone, and laughs when recalling a time that Bob Wiseman showed up to produce a band's record and exclaimed: "I can't work here. It's like a fort, not a studio!"

While measuring studio success is difficult and arguably irrelevant, Dave has been busy enough to require extra help. Jarrett Bartlett (no relation) came on board a few years back to help manage the workload around the time that Draves achieved what he considers a Bullhorn milestone in Kathleen Edwards' 2002 album Failer. "Kathleen's album made me feel like at least I'd achieved basic success as an engineer or producer. It proved that in my studio, in my backyard, I could get sounds that would hold up with other recordings. I could do something big.'"

Despite Little Bullhorn's impressive discography, Draves has found that most of his job satisfaction has come from the friends he has made along the way. "Looking back, the things I've valued aren't primarily the music that was made, but the relationships. You tend to value the human experiences." Dave had a chance to celebrate these relationships at the end of 2004 when his birthday party was capped off by the comeback performance of the Wooden Stars. "I believed that if they enjoyed playing together, they would do something more. I'm eager to see what they're going to do next."

Originally built as a practice space to accommodate his group Fishtales and other friends' bands, it wasn't long before Draves tried his hand at recording. "I was motivated by the fact that I liked the Wooden Stars," he says with a smile. "I just had to record them, so I rented a Fostex and we got to work one night. I had no gear and no way to monitor what we were recording, and when we listened back to the tape the next day there was nothing on it."

From these humble beginnings, Draves began to build Little Bullhorn, reading his share of Tape Op magazines along the way. He spent most of his free time seeking and acquiring vintage tube and analog gear, as well as a plethora of matador-themed décor from thrift stores. Over the years, Draves' connections and Pennysaver purchases have provided him with a collection of toys that would make any music geek jealous. Among the treasures are his two optigans, an egg-shaped chair with built-in speakers, and a steel plate reverb originally used in Montreal's RCA Victor studio. "I've always tried to reinvest money in the studio, as opposed to borrowing from the bank. I was inspired when I visited Chemical Sound [in Toronto] while the Wooden Stars were making their second record; they had quite a collection of interesting, vintage gear. It's neat to get all these old things and have them available during the creative process. It allows you to be spontaneous and create an environment where good things can happen."

One would argue that it's this philosophy that makes Draves' Little Bullhorn stand out from the pack, and drawn recent out-of-town clients like Howe Gelb. "My approach to recording is to make the studio as transparent as possible, and the process as un-intimidating as possible. I don't want the studio to have a bigger importance than the players. I think the tendency when bands are recording is to over-fix their mistakes. I would much rather allow for things to have an energy behind them, rather than be perfect."

The look and feel of the studio reflects this attitude. Cluttered with cables, lamps, and musical trinkets of all kinds, Little Bullhorn is a far cry from the sterile environment of a traditional recording studio. He admits that it's not for everyone, and laughs when recalling a time that Bob Wiseman showed up to produce a band's record and exclaimed: "I can't work here. It's like a fort, not a studio!"

While measuring studio success is difficult and arguably irrelevant, Dave has been busy enough to require extra help. Jarrett Bartlett (no relation) came on board a few years back to help manage the workload around the time that Draves achieved what he considers a Bullhorn milestone in Kathleen Edwards' 2002 album Failer. "Kathleen's album made me feel like at least I'd achieved basic success as an engineer or producer. It proved that in my studio, in my backyard, I could get sounds that would hold up with other recordings. I could do something big.'"

Despite Little Bullhorn's impressive discography, Draves has found that most of his job satisfaction has come from the friends he has made along the way. "Looking back, the things I've valued aren't primarily the music that was made, but the relationships. You tend to value the human experiences." Dave had a chance to celebrate these relationships at the end of 2004 when his birthday party was capped off by the comeback performance of the Wooden Stars. "I believed that if they enjoyed playing together, they would do something more. I'm eager to see what they're going to do next."