"I wasn't really worried whether or not I could pull it off," says 33 year old Ho Che Anderson. "I put pressure on myself, but I don't bow that much to external pressures." Of course, the cartoonist was just 19 when he began his biography of Martin Luther King, what he would come to call his "idiot quest through history." He was young, still living with his mother, working odd jobs and practising his art. "I was trying to break into the industry," he recalls, "taking the usual route of sending everybody copies of my work." He had dropped out of high school to focus on his craft perhaps inevitably, given that his father, a "junior revolutionary," named him after two famous rebels and he had already found success with an erotic thriller called I Want To Be Your Dog, a "smutty" S&M fable published by Seattle heavies Fantagraphics. Then came a phone call that would change his life. "I got a call from [the editor] at Fantagraphics. They wanted to do a series of historical books and asked me if I'd be interested in doing something on Martin Luther King." Anderson agreed. The year that followed was spent researching King biographies and accounts of the era, studying articles and photos and hours of news footage, then writing and rewriting scripts until a final version was ready. It was "profound and life-changing," he says.

"It started me thinking in ways I hadn't thought before. The era and the civil rights movement weren't really things that filtered through my mind at the time. I mean, [my] race is always a factor. It never leaves. But I was a kid, more concerned with partying and women. This project broadened my awareness: That there were great struggles, that there was a world before my time, that it didn't appear fully formed when I popped out."

At first, Anderson planned the book as a simple, 90-page summation of the man and his career. But when his script was finished, after nine months of toil, it was twice as long, and demanded a treatment as epic as its subject. "I like a larger-than-life approach to storytelling. I'm attracted to large themes and large images." The end result a year in the planning, another in the making was an affirmation of Anderson's effort and skill. King, Volume 1, released in August 1993, follows King's childhood in the 1930s to the first attempt on his life in 1960. Anderson took some dramatic liberties with the story, though he followed the "letter of history" as carefully as he could. "Some fudging was necessary for the gaps in research," he says, "though I didn't want to go off on wild speculations." And he didn't shy away from some of the unsavoury aspects of King's character, including his reputed womanising and self-aggrandising. "I wanted to tell the story well, not cheaply or half-assed."

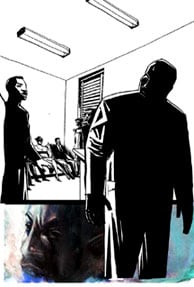

The book opens in delicate watercolour, but the bulk of the work is drawn in stark black and white, in jagged blocks that suggest paper cut-outs or wood prints. Light and shadow are treated with impunity; figures are stylised or blanched of detail (including, ironically, skin tone) or else shrouded in impenetrable darkness. It's all rather suggestive, given the topic, but Anderson says his approach to the art was more intuitive than prescriptive. "My stuff is really organic. [The metaphorical effect] is more a by-product of my style. And it adds a certain character to the book."

It would be nearly ten years before the next instalment appeared. He drew other stories in between (a series called Pop Life with cartoonist Wilfred Santiago, a strip called Zanana X for Toronto magazine The Word) and suffered what he terms a "financial meltdown," regrouping at his mom's house and getting back to the business of his epic. Now in his late 20s, Anderson had lived a little, and his artwork had developed. All this found its way into 2002's Volume 2, covering the years 1963 to 1965. It relies more on the computer effects Anderson had toyed with in Volume 1 stretching and filtering images, or repeating them across panels. Some sections, like the book's treatment of the 1963 March on Washington (King's legendary "I have a dream" speech) are impressionistic and reflective, Anderson's jarring illustrations swimming against grainy black and white photos, another technique he'd only begun to explore the first time around. Mixed media effects, so common in film and television, are a tricky business in comics. They risk alienating readers from the hand-drawn world that's supposed to engross them. But Anderson's style fits, thanks to his expert, cinematic pacing ("I'm a Martin Scorsese freak," he admits) and the fascinating documents of his real-life subject.

His style comes to fruition in the new book, and last chapter in the trilogy, in stores in early 2003. It will be a departure from the first two, he says, a full-colour volume and "a real shock to the system." The book begins with Lyndon Johnson signing the civil rights bill, and ends with King's tragic assassination in April 1968. For Anderson, it marks the end of a creative and deeply personal journey. "The thoughts, feelings and emotions that run though the books felt very close to me. It felt like I was assimilating these events, that I could see them more in three dimensions. But, in some ways, I don't feel any closer to King. In fact, I have more questions about him than I did when I started." Like all good art, Anderson's trilogy will no doubt leave readers with questions of their own. It might also help them find a few answers.

"It started me thinking in ways I hadn't thought before. The era and the civil rights movement weren't really things that filtered through my mind at the time. I mean, [my] race is always a factor. It never leaves. But I was a kid, more concerned with partying and women. This project broadened my awareness: That there were great struggles, that there was a world before my time, that it didn't appear fully formed when I popped out."

At first, Anderson planned the book as a simple, 90-page summation of the man and his career. But when his script was finished, after nine months of toil, it was twice as long, and demanded a treatment as epic as its subject. "I like a larger-than-life approach to storytelling. I'm attracted to large themes and large images." The end result a year in the planning, another in the making was an affirmation of Anderson's effort and skill. King, Volume 1, released in August 1993, follows King's childhood in the 1930s to the first attempt on his life in 1960. Anderson took some dramatic liberties with the story, though he followed the "letter of history" as carefully as he could. "Some fudging was necessary for the gaps in research," he says, "though I didn't want to go off on wild speculations." And he didn't shy away from some of the unsavoury aspects of King's character, including his reputed womanising and self-aggrandising. "I wanted to tell the story well, not cheaply or half-assed."

The book opens in delicate watercolour, but the bulk of the work is drawn in stark black and white, in jagged blocks that suggest paper cut-outs or wood prints. Light and shadow are treated with impunity; figures are stylised or blanched of detail (including, ironically, skin tone) or else shrouded in impenetrable darkness. It's all rather suggestive, given the topic, but Anderson says his approach to the art was more intuitive than prescriptive. "My stuff is really organic. [The metaphorical effect] is more a by-product of my style. And it adds a certain character to the book."

It would be nearly ten years before the next instalment appeared. He drew other stories in between (a series called Pop Life with cartoonist Wilfred Santiago, a strip called Zanana X for Toronto magazine The Word) and suffered what he terms a "financial meltdown," regrouping at his mom's house and getting back to the business of his epic. Now in his late 20s, Anderson had lived a little, and his artwork had developed. All this found its way into 2002's Volume 2, covering the years 1963 to 1965. It relies more on the computer effects Anderson had toyed with in Volume 1 stretching and filtering images, or repeating them across panels. Some sections, like the book's treatment of the 1963 March on Washington (King's legendary "I have a dream" speech) are impressionistic and reflective, Anderson's jarring illustrations swimming against grainy black and white photos, another technique he'd only begun to explore the first time around. Mixed media effects, so common in film and television, are a tricky business in comics. They risk alienating readers from the hand-drawn world that's supposed to engross them. But Anderson's style fits, thanks to his expert, cinematic pacing ("I'm a Martin Scorsese freak," he admits) and the fascinating documents of his real-life subject.

His style comes to fruition in the new book, and last chapter in the trilogy, in stores in early 2003. It will be a departure from the first two, he says, a full-colour volume and "a real shock to the system." The book begins with Lyndon Johnson signing the civil rights bill, and ends with King's tragic assassination in April 1968. For Anderson, it marks the end of a creative and deeply personal journey. "The thoughts, feelings and emotions that run though the books felt very close to me. It felt like I was assimilating these events, that I could see them more in three dimensions. But, in some ways, I don't feel any closer to King. In fact, I have more questions about him than I did when I started." Like all good art, Anderson's trilogy will no doubt leave readers with questions of their own. It might also help them find a few answers.