Like any DIY recording setup, JC/DC Studios has had a lot of obstacles in its 19-year history. So when John Collins and David Carswell received an eviction notice last spring, the producers took the forced relocation in stride. "We were just another group of people on the wrong side of the real estate market in Vancouver," says Collins, while Carswell sets up mics for a Veda Hille vocal session. The duo had been paying $2,000 a month for the top floor of the old Trocadero Building on West Hastings in Vancouver, where they'd been for six years. "Now they're asking $13,500 a month and that's in the space of six months. Welcome to Vancouver."

Collins and Carswell grew up together in West Vancouver. By the early '90s both were playing in mutual friend Nardwuar the Human Serviette's band, the Evaporators, with Collins on bass and Carswell on guitar.

Despite having little studio experience, the two hatched the idea to build their own recording space. "We started talking about buying some recording equipment in about '93. I was so into our Evaporators practices and I thought we should be recording them."

Armed with about $9,000, they set up in Carswell's parents' basement with a pair of TASCAM DA 88s, an 18-channel mixer and a bunch of microphones. "We worked for a year with just some home speakers as our monitors."

Their first clients were the band Meow ― later Maow ― featuring a young Neko Case on drums. "They just happened to be there the Saturday we were setting up," says Collins. "I'd never actually recorded a band before. We knew the basic principles. We got mics and put them in front of the drums. The base of it is quite simple. You can split hairs over technique, but we sure didn't that day."

The recordings were eventually released as the band's debut seven-inch on Mint Records, a relationship that continues to this day. "cub would come and record with us because we would see them every time we went out anyways either at a person's house or at a gig," he says. "There was no need to plan anything. It was all pretty organic."

If one of them wasn't out on tour ― which happens often ― bands often got two producers for the price of one. "We both are capable of making a record on our own but I prefer to split the work myself. It's more fun. There's a lot of frantic running around involved in recording a full band, especially when your equipment is always about 10 percent on the fritz."

Rather than carving out duties, the pair usually operate on a whoever-is-closest basis. "At the very beginning, I was the technical guy," says Collins. "I remember I explained the mixer to Dave one day because I had to go out and run an errand. I didn't want to be the guy running the mixer anymore. It evened out to the point where we were totally redundant. Whoever was closest would hit the record button."

After Carswell's parents sold their house, JC/DC was homeless. The two continued to produce, setting up shop wherever was convenient. "We couldn't have all our gear set up and ready to go but the way we did stuff it wasn't too bad."

They settled into the space on West Hastings around 2005, paying just $500 in rent for the building's top floor. At first the building lacked even running water and in their half-dozen years in the space, the heat never worked. "That was a nice sweet spot for what we were doing. It was generally really quiet and we had lots of room."

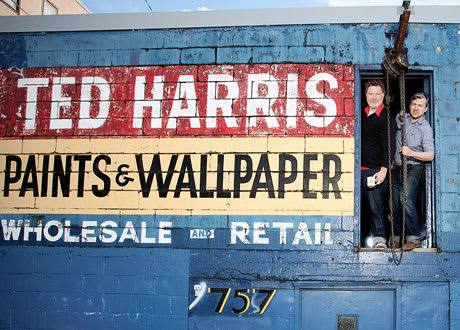

Belle and Sebastian's Stevie Jackson was the last musician recorded in that space while Toronto signer-songwriter Eamon McGrath was the first person to plug in an electric guitar and discover "the incredible hum" at their new home in the former Ted Harris Paints building.

As with every other set-up JC/DC has called home, their new home is a patchwork of cables and equipment. "The old place had its charms and the new place has its charms."

Currently, a seven-foot rack filled with pre-amps and assorted gear and a "standard assortment" of microphones fills out the studio. Their mixing board ― an eight-channel broadcast mixer gifted to them by UBC's radio station CITR ― is run through a Mac computer with a broken down Mackie mixer also in use. "We keep it because we own it and it sort of works." They've also been given a larger broadcast mixer from the CBC, but have yet to fix it up. "What Dave and I do, is we move into a totally weird derelict building and we just try to find enough equipment in our garage to make a studio out of it and just cross our fingers and hope that it sounds okay."

Collins and Carswell grew up together in West Vancouver. By the early '90s both were playing in mutual friend Nardwuar the Human Serviette's band, the Evaporators, with Collins on bass and Carswell on guitar.

Despite having little studio experience, the two hatched the idea to build their own recording space. "We started talking about buying some recording equipment in about '93. I was so into our Evaporators practices and I thought we should be recording them."

Armed with about $9,000, they set up in Carswell's parents' basement with a pair of TASCAM DA 88s, an 18-channel mixer and a bunch of microphones. "We worked for a year with just some home speakers as our monitors."

Their first clients were the band Meow ― later Maow ― featuring a young Neko Case on drums. "They just happened to be there the Saturday we were setting up," says Collins. "I'd never actually recorded a band before. We knew the basic principles. We got mics and put them in front of the drums. The base of it is quite simple. You can split hairs over technique, but we sure didn't that day."

The recordings were eventually released as the band's debut seven-inch on Mint Records, a relationship that continues to this day. "cub would come and record with us because we would see them every time we went out anyways either at a person's house or at a gig," he says. "There was no need to plan anything. It was all pretty organic."

If one of them wasn't out on tour ― which happens often ― bands often got two producers for the price of one. "We both are capable of making a record on our own but I prefer to split the work myself. It's more fun. There's a lot of frantic running around involved in recording a full band, especially when your equipment is always about 10 percent on the fritz."

Rather than carving out duties, the pair usually operate on a whoever-is-closest basis. "At the very beginning, I was the technical guy," says Collins. "I remember I explained the mixer to Dave one day because I had to go out and run an errand. I didn't want to be the guy running the mixer anymore. It evened out to the point where we were totally redundant. Whoever was closest would hit the record button."

After Carswell's parents sold their house, JC/DC was homeless. The two continued to produce, setting up shop wherever was convenient. "We couldn't have all our gear set up and ready to go but the way we did stuff it wasn't too bad."

They settled into the space on West Hastings around 2005, paying just $500 in rent for the building's top floor. At first the building lacked even running water and in their half-dozen years in the space, the heat never worked. "That was a nice sweet spot for what we were doing. It was generally really quiet and we had lots of room."

Belle and Sebastian's Stevie Jackson was the last musician recorded in that space while Toronto signer-songwriter Eamon McGrath was the first person to plug in an electric guitar and discover "the incredible hum" at their new home in the former Ted Harris Paints building.

As with every other set-up JC/DC has called home, their new home is a patchwork of cables and equipment. "The old place had its charms and the new place has its charms."

Currently, a seven-foot rack filled with pre-amps and assorted gear and a "standard assortment" of microphones fills out the studio. Their mixing board ― an eight-channel broadcast mixer gifted to them by UBC's radio station CITR ― is run through a Mac computer with a broken down Mackie mixer also in use. "We keep it because we own it and it sort of works." They've also been given a larger broadcast mixer from the CBC, but have yet to fix it up. "What Dave and I do, is we move into a totally weird derelict building and we just try to find enough equipment in our garage to make a studio out of it and just cross our fingers and hope that it sounds okay."