In Montreal, he is called the Pope of Comics. "He's the master," says Hlne B., a local cartoonist and shopkeeper at Fichtre, the city's premiere comix shop. "A lot of young fans are, 'Oh Valium, you're my god!'" His name is Henriette Valium, though he was born Patrick Henley in 1959, the fourth of five children, and "the only one who went wrong," he says. The notorious appellation was given him by a fellow cartoonist in the early 1980s. It stuck - these days, he even answers the phone as Valium.

He lives alone, mostly, though his four kids sometimes drop by, in a large apartment in a former shoe factory. His home is an industrial playground. A light table stands in the middle, next to a monstrous array of metal frames - part of the silk-screening press he uses to print his work: the psychedelic-cum-pornographic collages that leer from his walls, the comic pages that line his ceiling. A computer monitor hangs with chains, the sink is nailed to a brick wall, the tub and toilet are open concept. A girl in a cherry-red sweater, her lower lip pierced and pouting, sits fawning over Valium's every pronouncement, which often ends with the robust artist's shaved head glowing pink from exertion. She's one of his "hardcore groupies," he laughs. Valium is, after all, "believed by many to be the greatest French-Canadian cartoonist ever," according to a recent profile in a local zine. At 43, he is one of the underground comic world's elder statesmen, having over the past 20 years become a regular in almost every independent zine, compilation and catalogue in North America and Europe. He says he works to "keep [his] mental health in shape."

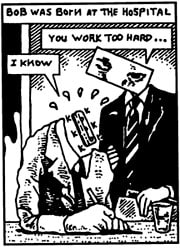

"I always produce, I'm hyperactive. I never watch TV, don't go to the cinema. I've got to draw - if I don't, I go nuts." One look at his hysterically dense work reveals as much. His comics are expertly drawn in a heavy, inked line that borrows much flavour from the early R. Crumb, one of Valium's key influences, along with Tintin's Herg and Italian cartoonist Jacovitti. Lurid murals border his pages, and every tiny opening is filled with another character or bodily discharge, another box of the semi-coherent koans with which he tells his stories, passages like, "Sick society! I've move from there due to odors sour pestilence of remorse...

"It covers my lack of English," he says of his unique semantics. "I'd like a reader to see it and think, 'This guy is on a huge dope high, it's the last day before he dies, even the language is affected.'" His trademark reversed Ns add to the effect. He is, nonetheless, meticulous - his last book, Coeur de Maman (Mother's Heart), took five years to complete. The previous collection took three. He prints all the work himself - some 200 copies of each book - and distributes them from his home, taking orders by email (valium90@hotmail.com). His books typically measure 11.5" by 17.5" - nearly the size of a newspaper, and large enough to be a truly immersive reading experience. "My books should by 4' by 6', and I'd sell the rack to go with it. Then you get some good stuff," he says, miming a joint at his lips and turning an enormous imaginary page, "and go, 'wow!'"

The first Valium collection, self-published in 1987, was a daunting 60-page album called 1000 Rectums. It was readers' initiation to his vast, disturbing universe: the urban streets dripping with gore, whole neighbourhoods festooned with electrical wire and populated by such rogues as "The Man from the Sewer." It also introduced his renowned Tintin parody: an infinitely nastier version called Nitnit. "Tintin was so fucking straight, a little schoolboy," Valium cackles, "It was easy to pick on him." Among Nitnit's adventures: bemoaning "the end of dope" as the apocalypse approaches, and viciously attacking his beloved cohorts.

But Valium's work goes deeper than mere parody. In his peculiar way, Valium explores decay, as in the rotting urban environments he obsessively renders, and his fascination with the various corruptions of the human body and mind, our illness and madness. His comics rant on subjects like "Science" or "Crisis," horrifically, sometimes nonsensically, often hilariously exposing our culture's fears and hypocrisies. A story called Sex is dappled with black censorship bars and sarcastically promises that a chaste life is rewarded by sex with God (drawn as a crucified cyclops with a massive erection). He's produced several portrait series: enlarged photos of religious or military figures, their faces superimposed with pornographic images scavenged from the trash or found online. The conflict between morality and authority - particularly religious authority - is a recurring theme. "Faith is a medical problem," he says. "A cancer of ideas. When you have faith in something, you've lost your lucidity." Sick Priests (Curs Malades), his distorted portraits of priests, so shocked his fellow artists when the series was exhibited at Montreal's Clark Gallery last year, one pulled her work from the gallery in protest.

"Sick Priests made everyone white as a ghost," Valium smiles. "What's the job of the artist? We take things and put them back in front of society. I didn't invent my images: I found them, they exist. I didn't hire a girl to suck a dog."

His approach has won him little favour with the Canadian art establishment. The artist is "officially on welfare" and was recently refused his fourth grant request. "The commentary I got was, 'We recognise Valium as a great artist, but his work is too sexist and too violent.' Too violent! And two weeks later those planes crashed in New York, to show you what real violence is." In Canada, he complains, there is no critical mass for underground work, or anything that challenges acceptable notions of taste. In France, however, Valium is a star, a darling of the avant-garde, where his work, in English and French, is called "brilliant" in the local press. Last month he flew to Marseilles to join Le Dernier Cri (Last Cry), France's revered underground art troupe, adding his skewed vision to their latest animated film. He has just finished recording a CD, a home-made collage of ambient noise, muffled voices and echoes. He has also completed a new portrait series of stunning plant/human hybrids called 41 Mutations, and is well into another comic collection. "When Crumb was drawing his [sexually explicit] stuff in the `70s, people looked at it in shock. Now it's cute. In 20 years, my work will be cute too."

He lives alone, mostly, though his four kids sometimes drop by, in a large apartment in a former shoe factory. His home is an industrial playground. A light table stands in the middle, next to a monstrous array of metal frames - part of the silk-screening press he uses to print his work: the psychedelic-cum-pornographic collages that leer from his walls, the comic pages that line his ceiling. A computer monitor hangs with chains, the sink is nailed to a brick wall, the tub and toilet are open concept. A girl in a cherry-red sweater, her lower lip pierced and pouting, sits fawning over Valium's every pronouncement, which often ends with the robust artist's shaved head glowing pink from exertion. She's one of his "hardcore groupies," he laughs. Valium is, after all, "believed by many to be the greatest French-Canadian cartoonist ever," according to a recent profile in a local zine. At 43, he is one of the underground comic world's elder statesmen, having over the past 20 years become a regular in almost every independent zine, compilation and catalogue in North America and Europe. He says he works to "keep [his] mental health in shape."

"I always produce, I'm hyperactive. I never watch TV, don't go to the cinema. I've got to draw - if I don't, I go nuts." One look at his hysterically dense work reveals as much. His comics are expertly drawn in a heavy, inked line that borrows much flavour from the early R. Crumb, one of Valium's key influences, along with Tintin's Herg and Italian cartoonist Jacovitti. Lurid murals border his pages, and every tiny opening is filled with another character or bodily discharge, another box of the semi-coherent koans with which he tells his stories, passages like, "Sick society! I've move from there due to odors sour pestilence of remorse...

"It covers my lack of English," he says of his unique semantics. "I'd like a reader to see it and think, 'This guy is on a huge dope high, it's the last day before he dies, even the language is affected.'" His trademark reversed Ns add to the effect. He is, nonetheless, meticulous - his last book, Coeur de Maman (Mother's Heart), took five years to complete. The previous collection took three. He prints all the work himself - some 200 copies of each book - and distributes them from his home, taking orders by email (valium90@hotmail.com). His books typically measure 11.5" by 17.5" - nearly the size of a newspaper, and large enough to be a truly immersive reading experience. "My books should by 4' by 6', and I'd sell the rack to go with it. Then you get some good stuff," he says, miming a joint at his lips and turning an enormous imaginary page, "and go, 'wow!'"

The first Valium collection, self-published in 1987, was a daunting 60-page album called 1000 Rectums. It was readers' initiation to his vast, disturbing universe: the urban streets dripping with gore, whole neighbourhoods festooned with electrical wire and populated by such rogues as "The Man from the Sewer." It also introduced his renowned Tintin parody: an infinitely nastier version called Nitnit. "Tintin was so fucking straight, a little schoolboy," Valium cackles, "It was easy to pick on him." Among Nitnit's adventures: bemoaning "the end of dope" as the apocalypse approaches, and viciously attacking his beloved cohorts.

But Valium's work goes deeper than mere parody. In his peculiar way, Valium explores decay, as in the rotting urban environments he obsessively renders, and his fascination with the various corruptions of the human body and mind, our illness and madness. His comics rant on subjects like "Science" or "Crisis," horrifically, sometimes nonsensically, often hilariously exposing our culture's fears and hypocrisies. A story called Sex is dappled with black censorship bars and sarcastically promises that a chaste life is rewarded by sex with God (drawn as a crucified cyclops with a massive erection). He's produced several portrait series: enlarged photos of religious or military figures, their faces superimposed with pornographic images scavenged from the trash or found online. The conflict between morality and authority - particularly religious authority - is a recurring theme. "Faith is a medical problem," he says. "A cancer of ideas. When you have faith in something, you've lost your lucidity." Sick Priests (Curs Malades), his distorted portraits of priests, so shocked his fellow artists when the series was exhibited at Montreal's Clark Gallery last year, one pulled her work from the gallery in protest.

"Sick Priests made everyone white as a ghost," Valium smiles. "What's the job of the artist? We take things and put them back in front of society. I didn't invent my images: I found them, they exist. I didn't hire a girl to suck a dog."

His approach has won him little favour with the Canadian art establishment. The artist is "officially on welfare" and was recently refused his fourth grant request. "The commentary I got was, 'We recognise Valium as a great artist, but his work is too sexist and too violent.' Too violent! And two weeks later those planes crashed in New York, to show you what real violence is." In Canada, he complains, there is no critical mass for underground work, or anything that challenges acceptable notions of taste. In France, however, Valium is a star, a darling of the avant-garde, where his work, in English and French, is called "brilliant" in the local press. Last month he flew to Marseilles to join Le Dernier Cri (Last Cry), France's revered underground art troupe, adding his skewed vision to their latest animated film. He has just finished recording a CD, a home-made collage of ambient noise, muffled voices and echoes. He has also completed a new portrait series of stunning plant/human hybrids called 41 Mutations, and is well into another comic collection. "When Crumb was drawing his [sexually explicit] stuff in the `70s, people looked at it in shock. Now it's cute. In 20 years, my work will be cute too."