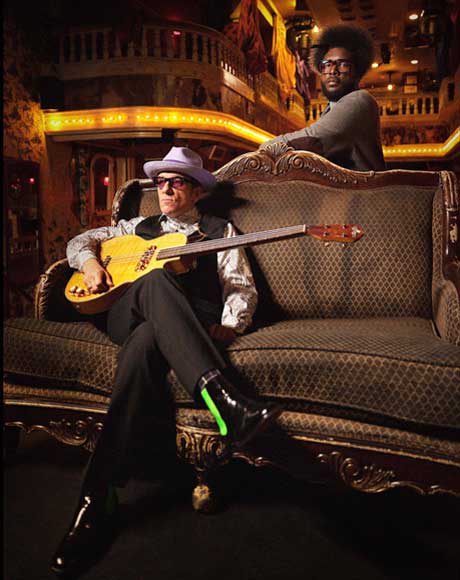

Many of Elvis Costello's previous collaborations have produced stunning results, but when word leaked earlier this year that he was making an album with the Roots, alarm bells started going off that there was potentially another Lou Reed/Metallica-scale train wreck ahead. However, Wise Up Ghost is anything but. Drawing from his love of vintage soul — one of the Roots' specialties — while on several tracks re-imagining older songs such as "Pills And Soap," Costello sounds more energized, and angry, than he has in years. Exclaim! spoke to him about the process behind Wise Up Ghost, as well as how he has adapted to life in Vancouver with his wife, jazz artist Diana Krall.

Who made the first move on this record?

We kind of came into it through the process of me being on the Fallon show on a number of occasions. We had a different assignment each time with those three appearances: One was to play an older song of mine; the next to play a new song of mine; the third to play a Bruce Springsteen song. What we brought to those arrangements really laid out a lot of the way we went about writing and recording this record. Ahmir [?uestlove] will tell it that it was one of the things on their mind when they took the Fallon show gig was that they would possibly be in proximity to people who the end result might be some adventures like this. My name was apparently mentioned, but nobody had said it to me.

When I first went on the show, I didn't know what the protocol was about the Roots accompanying people. I'd seen them do it on a number of nights, but I didn't know how tight they were with those artists. They could have been friends from another occasion; I didn't think it was necessarily something you could request. I didn't happen to have my band the first time I went on the show because I was talking about the Spectacle television program, and I remember asking Karriem Riggins, who's a friend of ?uest who plays drums with Diana [Krall], "Do you think they'd play with me?" And he said, "Yeah, I think they probably would." Maybe he knew a bit more about what they knew about me than I did. So we were both of us looking at it from different ways.

By the time we did the first [appearance], I had already been in and done a recording on a record they were making in secret of Difford and Tilbrook [of Squeeze] songs, which actually hasn't come out yet. They had assembled all sorts of different people to sing those songs — Edie Brickell, Erykah Badu, and of course I produced a number of songs that were in that collection, so it was a thrill to come in and sing one of Chris and Glenn's songs since they're old pals. But it was an utterly different version. You might say that was one of the little steps along the way, and I'd almost forgotten about that until the other day. So when [Roots engineer] Steven Mandel sent me the first loop with the idea that it be a way of arranging "Pills And Soap," I said I don't want to just do a literal re-recording, I want to pull it apart; I want to insert some other verses from other sources where I carried on the theme of that song in later songs and bring it right up to date — make this for today, so we're not just doing a retrospective.

That was the method we used for about four songs, and they were very successful because they ended up creating a new story out of the combination of these lyrics. I knew what they meant, and they meant something slightly different because we were repeating them now in relation to the circumstances of today. In "Refuse To Be Saved," there's a verse that says, "They're hunting us down here with Liberty's light / A handshaking double talking procession of the mighty." Well, I wrote that when the Americans invaded Panama, and that was a minor little colonial skirmish compared with the lie we were told going into Iraq. But it was the same thing, "We're going there to liberate," not create absolute chaos, or to pursue the wrong enemy in the wrong territory. So of course if bears repeating.

But when you're doing it with the thoughtful music I was handed by Ahmir and the parts we developed at the last minute — the incredible orchestrations by Brent Fischer — it was worthwhile. It led us to then write two-thirds of the record with no references to the past except a few musical configurations. The methodology of this record obviously is something commonplace in a lot of contemporary recordings, including hip-hop, of taking a foundation of a loop or, in many cases, a sample of us jamming, so we're sampling ourselves. By the time we've finished adding to it, it isn't important that we're repeating the same two chords or the same structure of music for 16 bars or for two bars. How is that different than if I was just playing three chords on a rhythm guitar? It's not, it just pins it down, and then you tell the story over the top. It's just a question of what you think music is.

It seems like you were immediately taken with this new way of writing.

The novelty of the method was certainly a provocation to the imagination. But it was also nothing more than I was trying to write some melodies, like with "Cinco Minutos" and "Viceroy's Row," that are laid over two chords, where there isn't an anticipated progression, where you're always imagining what's going to occur. It creates a different kind of tension and asks a different question of the melodies. It asks a different question of the vocalist as well at times, all of which makes the music unusual. You have something going around in one continuity, and then you have a horn line offset from that, and then a vocal melody that's off-centre again, all of which makes it hopefully arresting to listen to — but at times beautiful, like when you have La Marisoul's voice coming in, a sumptuous voice compared to mine, and she puts some humanity into the character of this daughter who's waiting for her father to arrive and he's never going to arrive.

In working on this album, did you implement any lessons you might have learned working with soul legend Allen Toussaint on The River In Reverse?

I had the experience of singing those Allen songs on a number of occasions with Pete Thomas on drums, who's a tremendous drummer — obviously, we've worked together for 35 years — and with Allen's regular drummer Herman [LeBeaux]. Also, singing the songs alone with Allen where the flow was coming from just his piano was a brilliant thing, but I think everything you learn as you're going along, and what you absorb, is part of what you know.

I've worked with the method of recording records instrument by instrument — Spike was recorded like that — and I've worked from a rhythmic foundation that wasn't being played by a drummer. That goes back to "Green Shirt" from Armed Forces, where there's a Moog loop cycling round and round that was driving that track. Or "When I Was Cruel," where it's a beat box and a sample behind a hypnotic ballad. So, you can make comparisons, but they only hint at what we started to do here.

You're dealing with people who are fluent in this method, and I've got the curiosity about what happens when my voice goes with that. They've got the curiosity about what happens when they come out of that. Ahmir will say, "We didn't want it to be too funky," as if such a thing could be a problem. I know what he means; he didn't want it to sound like an affectation, and I didn't want it to either. It would just be idiotic to assume that I would even think about trying to do a rap record, but there are plenty of songs I've done where the declamation of the lyric has been more important than the melodiousness of my voice. Right from the beginning, "Pump It Up" is from a noble lineage of one-note songs, where the rhythm is driving it as opposed to melodies that, as they used to say, the milkman can whistle.

Had you been following at all what labels like Daptone Records had been doing the past few years in terms of soul music?

You hear some records where they evoke things that I really love, and sometimes get close to the feeling of them. It's great that people really love and cherish that music and want to create something new in its image. The age I am, when I heard that music from the '60s for the first time, the memories are so vivid. But it was just one or two records in different spots. Then when I came to America in 1977, I haunted every record shop trying to find out more about those singers that I liked. Suddenly I could get a whole album by James Carr, and not just one song. Then you hear something made in Brooklyn that's trying to get at that kind of feeling. Of course that's good. I don't know that it's the same thing that we're doing, but that doesn't mean we're doing something better or they're doing something better. They're all things I enjoy.

Another thing I find interesting is Wise Up Ghost's packaging, with the cover reminiscent of Allen Ginsberg's Howl, which seems intentional.

There's two stories in that. One is that 30 years ago I made a country record in Nashville of my favourite country songs [Almost Blue]. That was where my head was at; I knew I couldn't sing them half as well as the original artists, but I also knew that an awful lot of people had never heard George Jones or Charlie Rich. They didn't share my interest in it, so I thought it was a good case to just let people hear these beautiful songs that I felt strongly about. The cover of that album was a parody of a Blue Note Records cover. So, I thought since this album was actually on Blue Note, we had to do something different. It was [Blue Note president] Don Was's idea, and I suppose he was paying me a compliment in saying that he wanted the lyrics to be printed as a book. I've never had any illusions that I'm a poet, because that's a different skill, a different art. Those are people who can evoke music without anything being played.

I did notice that last year you took part in a PEN event honouring Chuck Berry and Leonard Cohen.

That was specifically an award for lyrics.

Yes, but it made me wonder whether you might feel that songwriting — at least since Bob Dylan — has assumed the cultural status that literature once had, or perhaps now shares?

You can make an argument that movies supplanted the symphony. Symphonies used to be where the court and the intellectual segment of society would go to hear the promotion of the spiritual, emotional and sometimes political aspirations of the artist. There's the story of Beethoven dedicating his Third Symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte and then scratching it out when he realized Napoleon was a tyrant. You might say that Birth of A Nation is one kind of statement that D.W. Griffith made about America, and Apocalypse Now is another one.

Those big statements about where society or the country is going stopped being made in music, and you can tell yourself that because lyrics from hit songs are ubiquitous, or because Ira Gershwin didn't write phrases that would have been sung in Paris during the revolution. But he's not inherently the same thing. They are different. I don't subscribe to the idea that either one is a superior form either. If it were like, us poets are bequeathing on you lyricists this nobility, it would be patronizing. I don't think that's what PEN were doing, I think they made a distinction. It's just a very high standard of writing in Leonard Cohen's work, and as Leonard Cohen would say, we're all footnotes to the work of Chuck Berry. "And like a footnote, I'll be brief. Thank you friends." That was one of the most elegant acceptance speeches I've ever heard. All that Leonard said that day — he did say a few other things, but not that many — he gave all credit to Chuck. So, I'm not being argumentative, I just believe that novelists are novelists, historians are historians, and poets are poets. Some of them sing and some of them don't.

Lastly, how have we Canadians been treating you since you've been here?

I have to say that it's a place I can feel at home — the brief time that my family and I are able to be in the west. There are parts of Canada that I haven't been to in many years, and there are parts of Canada that for some reason I never managed to play. After 35 years there are still places where I'm making my debut — I managed to play Luxembourg this year for the first time, and Derry [Ireland] for the first time — so there's still hope for Nova Scotia. I mean, my hope for it. Both Diana and I are fortunate to be able to work as much as we do so we can have a few short weeks away from the stage to spend with our boys in Vancouver. We have a lot of great friends there.

Who made the first move on this record?

We kind of came into it through the process of me being on the Fallon show on a number of occasions. We had a different assignment each time with those three appearances: One was to play an older song of mine; the next to play a new song of mine; the third to play a Bruce Springsteen song. What we brought to those arrangements really laid out a lot of the way we went about writing and recording this record. Ahmir [?uestlove] will tell it that it was one of the things on their mind when they took the Fallon show gig was that they would possibly be in proximity to people who the end result might be some adventures like this. My name was apparently mentioned, but nobody had said it to me.

When I first went on the show, I didn't know what the protocol was about the Roots accompanying people. I'd seen them do it on a number of nights, but I didn't know how tight they were with those artists. They could have been friends from another occasion; I didn't think it was necessarily something you could request. I didn't happen to have my band the first time I went on the show because I was talking about the Spectacle television program, and I remember asking Karriem Riggins, who's a friend of ?uest who plays drums with Diana [Krall], "Do you think they'd play with me?" And he said, "Yeah, I think they probably would." Maybe he knew a bit more about what they knew about me than I did. So we were both of us looking at it from different ways.

By the time we did the first [appearance], I had already been in and done a recording on a record they were making in secret of Difford and Tilbrook [of Squeeze] songs, which actually hasn't come out yet. They had assembled all sorts of different people to sing those songs — Edie Brickell, Erykah Badu, and of course I produced a number of songs that were in that collection, so it was a thrill to come in and sing one of Chris and Glenn's songs since they're old pals. But it was an utterly different version. You might say that was one of the little steps along the way, and I'd almost forgotten about that until the other day. So when [Roots engineer] Steven Mandel sent me the first loop with the idea that it be a way of arranging "Pills And Soap," I said I don't want to just do a literal re-recording, I want to pull it apart; I want to insert some other verses from other sources where I carried on the theme of that song in later songs and bring it right up to date — make this for today, so we're not just doing a retrospective.

That was the method we used for about four songs, and they were very successful because they ended up creating a new story out of the combination of these lyrics. I knew what they meant, and they meant something slightly different because we were repeating them now in relation to the circumstances of today. In "Refuse To Be Saved," there's a verse that says, "They're hunting us down here with Liberty's light / A handshaking double talking procession of the mighty." Well, I wrote that when the Americans invaded Panama, and that was a minor little colonial skirmish compared with the lie we were told going into Iraq. But it was the same thing, "We're going there to liberate," not create absolute chaos, or to pursue the wrong enemy in the wrong territory. So of course if bears repeating.

But when you're doing it with the thoughtful music I was handed by Ahmir and the parts we developed at the last minute — the incredible orchestrations by Brent Fischer — it was worthwhile. It led us to then write two-thirds of the record with no references to the past except a few musical configurations. The methodology of this record obviously is something commonplace in a lot of contemporary recordings, including hip-hop, of taking a foundation of a loop or, in many cases, a sample of us jamming, so we're sampling ourselves. By the time we've finished adding to it, it isn't important that we're repeating the same two chords or the same structure of music for 16 bars or for two bars. How is that different than if I was just playing three chords on a rhythm guitar? It's not, it just pins it down, and then you tell the story over the top. It's just a question of what you think music is.

It seems like you were immediately taken with this new way of writing.

The novelty of the method was certainly a provocation to the imagination. But it was also nothing more than I was trying to write some melodies, like with "Cinco Minutos" and "Viceroy's Row," that are laid over two chords, where there isn't an anticipated progression, where you're always imagining what's going to occur. It creates a different kind of tension and asks a different question of the melodies. It asks a different question of the vocalist as well at times, all of which makes the music unusual. You have something going around in one continuity, and then you have a horn line offset from that, and then a vocal melody that's off-centre again, all of which makes it hopefully arresting to listen to — but at times beautiful, like when you have La Marisoul's voice coming in, a sumptuous voice compared to mine, and she puts some humanity into the character of this daughter who's waiting for her father to arrive and he's never going to arrive.

In working on this album, did you implement any lessons you might have learned working with soul legend Allen Toussaint on The River In Reverse?

I had the experience of singing those Allen songs on a number of occasions with Pete Thomas on drums, who's a tremendous drummer — obviously, we've worked together for 35 years — and with Allen's regular drummer Herman [LeBeaux]. Also, singing the songs alone with Allen where the flow was coming from just his piano was a brilliant thing, but I think everything you learn as you're going along, and what you absorb, is part of what you know.

I've worked with the method of recording records instrument by instrument — Spike was recorded like that — and I've worked from a rhythmic foundation that wasn't being played by a drummer. That goes back to "Green Shirt" from Armed Forces, where there's a Moog loop cycling round and round that was driving that track. Or "When I Was Cruel," where it's a beat box and a sample behind a hypnotic ballad. So, you can make comparisons, but they only hint at what we started to do here.

You're dealing with people who are fluent in this method, and I've got the curiosity about what happens when my voice goes with that. They've got the curiosity about what happens when they come out of that. Ahmir will say, "We didn't want it to be too funky," as if such a thing could be a problem. I know what he means; he didn't want it to sound like an affectation, and I didn't want it to either. It would just be idiotic to assume that I would even think about trying to do a rap record, but there are plenty of songs I've done where the declamation of the lyric has been more important than the melodiousness of my voice. Right from the beginning, "Pump It Up" is from a noble lineage of one-note songs, where the rhythm is driving it as opposed to melodies that, as they used to say, the milkman can whistle.

Had you been following at all what labels like Daptone Records had been doing the past few years in terms of soul music?

You hear some records where they evoke things that I really love, and sometimes get close to the feeling of them. It's great that people really love and cherish that music and want to create something new in its image. The age I am, when I heard that music from the '60s for the first time, the memories are so vivid. But it was just one or two records in different spots. Then when I came to America in 1977, I haunted every record shop trying to find out more about those singers that I liked. Suddenly I could get a whole album by James Carr, and not just one song. Then you hear something made in Brooklyn that's trying to get at that kind of feeling. Of course that's good. I don't know that it's the same thing that we're doing, but that doesn't mean we're doing something better or they're doing something better. They're all things I enjoy.

Another thing I find interesting is Wise Up Ghost's packaging, with the cover reminiscent of Allen Ginsberg's Howl, which seems intentional.

There's two stories in that. One is that 30 years ago I made a country record in Nashville of my favourite country songs [Almost Blue]. That was where my head was at; I knew I couldn't sing them half as well as the original artists, but I also knew that an awful lot of people had never heard George Jones or Charlie Rich. They didn't share my interest in it, so I thought it was a good case to just let people hear these beautiful songs that I felt strongly about. The cover of that album was a parody of a Blue Note Records cover. So, I thought since this album was actually on Blue Note, we had to do something different. It was [Blue Note president] Don Was's idea, and I suppose he was paying me a compliment in saying that he wanted the lyrics to be printed as a book. I've never had any illusions that I'm a poet, because that's a different skill, a different art. Those are people who can evoke music without anything being played.

I did notice that last year you took part in a PEN event honouring Chuck Berry and Leonard Cohen.

That was specifically an award for lyrics.

Yes, but it made me wonder whether you might feel that songwriting — at least since Bob Dylan — has assumed the cultural status that literature once had, or perhaps now shares?

You can make an argument that movies supplanted the symphony. Symphonies used to be where the court and the intellectual segment of society would go to hear the promotion of the spiritual, emotional and sometimes political aspirations of the artist. There's the story of Beethoven dedicating his Third Symphony to Napoleon Bonaparte and then scratching it out when he realized Napoleon was a tyrant. You might say that Birth of A Nation is one kind of statement that D.W. Griffith made about America, and Apocalypse Now is another one.

Those big statements about where society or the country is going stopped being made in music, and you can tell yourself that because lyrics from hit songs are ubiquitous, or because Ira Gershwin didn't write phrases that would have been sung in Paris during the revolution. But he's not inherently the same thing. They are different. I don't subscribe to the idea that either one is a superior form either. If it were like, us poets are bequeathing on you lyricists this nobility, it would be patronizing. I don't think that's what PEN were doing, I think they made a distinction. It's just a very high standard of writing in Leonard Cohen's work, and as Leonard Cohen would say, we're all footnotes to the work of Chuck Berry. "And like a footnote, I'll be brief. Thank you friends." That was one of the most elegant acceptance speeches I've ever heard. All that Leonard said that day — he did say a few other things, but not that many — he gave all credit to Chuck. So, I'm not being argumentative, I just believe that novelists are novelists, historians are historians, and poets are poets. Some of them sing and some of them don't.

Lastly, how have we Canadians been treating you since you've been here?

I have to say that it's a place I can feel at home — the brief time that my family and I are able to be in the west. There are parts of Canada that I haven't been to in many years, and there are parts of Canada that for some reason I never managed to play. After 35 years there are still places where I'm making my debut — I managed to play Luxembourg this year for the first time, and Derry [Ireland] for the first time — so there's still hope for Nova Scotia. I mean, my hope for it. Both Diana and I are fortunate to be able to work as much as we do so we can have a few short weeks away from the stage to spend with our boys in Vancouver. We have a lot of great friends there.