Stephen McBean is a man of the past; he likes his records black, his sounds vintage and his art to come on 12-inch squares. He embraces the rock'n'roll of old, its sentiments, attitudes and designs. And really, McBean's the type of guy who shouldn't fit into a modern context, yet strangely enough, he does. For the last three years, the 38-year-old Jesus-like figure has fronted one of the most exciting acts on the landscape: Black Mountain. In the group's brief history, they've become the outlet for his retro-rock fantasies and, in the process, garnered him a reputation for being quite the rock revivalist. Yet Black Mountain do not simply engage in regurgitating idol worship, but rather transform the past into something very much their own, and perhaps more importantly, very much of the present.

First on the agenda of their anachronistic ambitions is reviving a traditional idea in how music is presented. "We wanted to get back to the album-album thing, says McBean, the Vancouver group's vocalist, guitar player and principal songwriter, of their sophomore effort, In the Future. "With today's culture of music listening with computers, iPods and even phones now, if you go download an album, you just don't get the whole vibe and the beauty of it all. Music has saved me more than once, just sitting down with a record and looking at the cover, trying to figure out what it means, reading the lyrics and all that stuff.

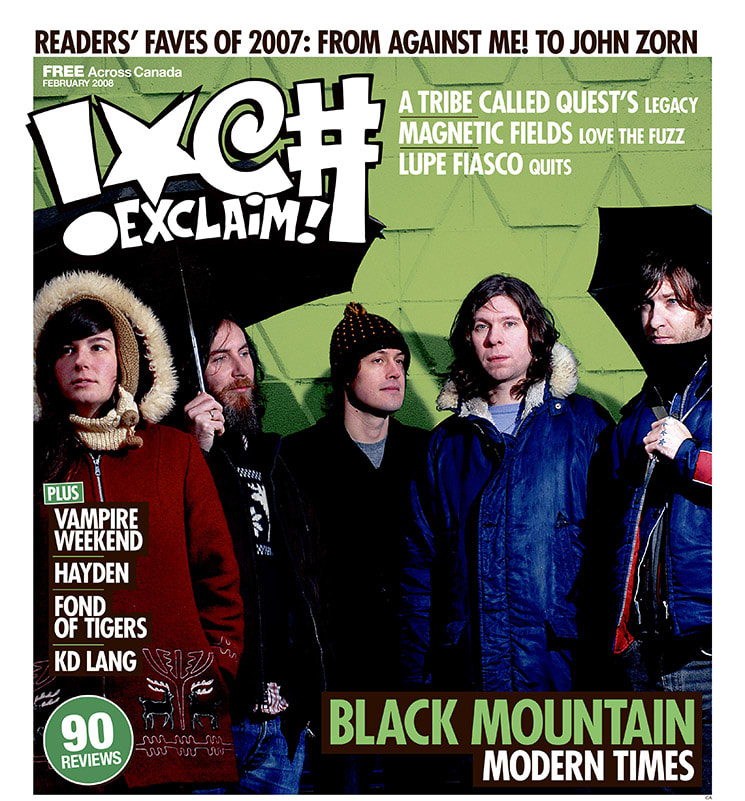

"I just want some kid to have the same experience that I had with a record at some point. And I'm sure there will probably be a kid who will get baked, start trippin' out on the album cover and be like, 'Ah, dude,' just having that experience with music where it hits you in the heart, in the right place at the right time. Black Mountain's new long-player certainly is an experience. With ten tracks, a 60-minute running time and album art that rivals any Pink Floyd jacket, In the Future is downright overwhelming, demanding you listen, listen and then listen again to absorb it all. It shows the group's members — McBean, Joshua Wells (drums), Amber Webber (vocals), Matt Camirand (bass) and Jeremy Schmidt (keyboards) — stretching far beyond their previous work and doing much more than just resurrecting the ghosts of rock'n'roll past.

In the Future arrives three years after Black Mountain's self-titled debut launched the West Coast five-piece into a whirlwind of acclaim, press and international recognition. Their debut's adventurous reconfiguration of '70s-styled rock hit that sought-after spot where universal appeal meets cult fascination. Garnering one rave review after another, it earned a spot on many critics' best-of lists and caught the eye of the British press, who quickly picked up on the band's hippie-like image and twisted it into fabricated stories of drug-fuelled communes and blissed-out Black Mountain disciples.

In the three years since its release, Black Mountain landed a coveted opening spot on Coldplay's world tour, got "Stay Free" (included on In the Future) onto the Spider-Man 3 soundtrack, and joined Aphex Twin and Julian Cope at the Portishead-curated All Tomorrow's Parties festival in the UK last December.

"You know how everyone has their own rock'n'roll dreams?" McBean asks. "I guess maybe it's because I was a punk kid, but my rock'n'roll dream was to put out a seven-inch and go on tour, and that was it. Now we're long past that."

Getting "long past that" has been a lengthy and often less than glamorous journey for Black Mountain; the group is neither McBean's nor his band-mates' first musical effort by a long shot. McBean's previous project, Jerk with a Bomb, struggled on the Canadian indie scene for years before trekking up to the greener pastures of Black Mountain.

Jerk with a Bomb — a band that at different times housed all of Black Mountain's members except Schmidt, who joined later — first took root in the mid-'90s as a duo composed of McBean and Joshua Wells. At the time, McBean says the folksy rock/country project was a way to escape the angst-driven bands he played in as a teenager, punk-metal outfits like Mission of Christ and Gus, and later on, the short-lived, post-punk-leaning Ex-Dead Teenager (whose only release was released last year on the now-defunct CD-R label, 1777rex).

Jerk with a Bomb had no MySpace or YouTube to kick-start their career, so they began the old-fashioned way: with a demo tape, which fell into the hand of Scratch Records' Keith Parry, who in turn signed the group. Over the years, the Vancouver label put out a handful of JWAB releases, which displayed potential and ambition, but largely fell on deaf ears. "None of the Jerk with a Bomb stuff sold well at all," McBean recalls. "I think it took four or five years for the first Jerk with a Bomb on Scratch [The Old Noise] to get through its first thousand copies." These were lean times for the duo, playing hit-and-miss shows across the country, sleeping in unheated vans and working part-time at the Scratch retail store to avoid eviction notices. By 2003, however, the tide began to change for JWAB when they stretched into more prog-y, stoner-rock territory with their final album, Pyrokinesis. The shift came in part from a line-up change that enlisted two more future Black Mountain recruits: vocalist Amber Webber, who joined JWAB full-time, and bassist Matt Camirand, a former Black Halo who began providing the occasional live support and eventually replaced Pyrokinesis' German multi-instrumentalist, Christoph Hofmeister.

With this new blood and sound, the line where Jerk with a Bomb ended and Black Mountain began blurs. As legend has it, one night before a local show, McBean had a dream JWAB turned into a new band: Black Mountain. When he awoke, he whipped up a banner and a song featuring this new band name. That night, they played as Black Mountain for the first time.

McBean and company decided to keep the new name for good, dropping JWAB's down-and-out folk sounds for the vintage Velvets and Sabbath-like tactics that Pyrokinesis hinted at and Black Mountain fully embraced. "It was almost like a release," McBean says. "It was just like this new thing. I mean, I loved Jerk with a Bomb, but it got to a point where I was done with it, and it almost felt like I was through with that part of my life. I didn't want to stand in front of people and sing sad songs about being heartbroken anymore."

In the Future is much more than just songs for the broken-hearted. Over four sides of vinyl, there are bottom-heavy, bad-boogie-ballin' attacks, prog-fashioned keyboard numbers, soulful freedom songs, occasionally all of the above. There are lyrics of black magic rituals, flower trains, hounds of hell and tyrants dying by the sword. And there are some of the group's most intense, full-on rock moments as well as some of their most tranquil and tender. Together, it adds up to a magnificently sequenced album lover's album with enough hit-the-spot nuggets for the casual shuffler. With the album comes an amplified sense of collaboration — the band sound like one solid unit where each member adds a unique stamp. This especially evident with Webber, whose dramatic, operatic voice wavers stronger than ever behind and in front of McBean's, and Schmidt, his keyboards given free range to sound like the sonic equivalent of outer space as their celestial tones float over Camirand's low bass rumble and Wells's tom-heavy drum patterns.

"Arranging was way more a group thing," McBean explains. "With the first one, a lot of those songs were already written and then Matt and Jeremy came in and did their thing on it. But this time, a lot of stuff was worked on together live first, and everyone would bring in different ideas."

Overall, Black Mountain has made a more varied and heightened musical experience and proven they have evolved far beyond simple rock revivalists, or just McBean's band. "We didn't want to repeat the formula of the first record, having people talk about the Velvets and Sabbath thing again," McBean says. "We had some songs that we could have put on that fit into that, but it just seemed like, 'Why bother? We've already done that.'"

Helping this shift was John Congleton, who mixed all but one of the album's tracks, and who McBean points to as having a major impact on Black Mountain's sonic growth. Without the long-time producer, "the record would have sounded a lot more like the first one," McBean says. Interestingly, it wasn't Congleton's work with rock bands like Polyphonic Spree and Explosions in the Sky that attracted Black Mountain to him; it was what the producer has done with hip-hop and R&B artists like the Roots and R. Kelly. "To me, the album is a logical progression from the first one," says keyboardist Jeremy Schmidt. "It's not a total about-face or anything. There are things are different and, in our minds, improved on. I think there are more fleshed out ideas in terms of our ensemble playing and the contributions of everyone." And while McBean highlights how happy he and the rest of the band are with In the Future, the record was by no means quick and easy. In fact, this is the second time Black Mountain tried to follow up their debut.

After wrapping up tour dates in support of their first album, the band originally entered the studio in March 2006, but most of the material from those sessions ended up on the cutting-room floor, and Black Mountain ended up taking a hiatus. "Bits and pieces of that session worked out, but not all of it, McBean explains. "We had a bunch of songs, but we didn't really have an album; they weren't working together in the right way albums do. And I think our brains were all working on different waves at that point, so we just decided to wait until the band seemed exciting to us again." During this downtime, each member took the opportunity to pursue varied side projects. McBean released the critically adored Axis of Evol under his alter ego, Pink Mountaintops. Wells and Webber recorded an album of gloomy melodrama as Lightning Dust. Camirand set to work on a pair of albums with his Americana-leaning Blood Meridian (which also features Wells on drums), and Schmidt re-released the meditation-inducing sounds of The Enchanter Persuaded, his Sinoia Caves debut.

These creative outlets provided new people to bounce ideas off, Schmidt says, and a place to mine for inspiration that fed back into Black Mountain. "All of our side projects, in one way or another, inform our individual contributions to Black Mountain," he says. "But I think if you put all the side projects together it wouldn't sound like Black Mountain, and if you took Black Mountain all apart, it wouldn't sound like all the individual projects. They're just amalgamations of different aesthetics and sensibilities." McBean also points to the healthy impact the projects had on the band leading up to In the Future. "If we had made the record earlier and not all gone off and done our other little things, this album would not have been as good," McBean says. "It would have been, 'Hey, another record just for the sake of a record.' And none of us really want any of this to become a job — we want it to come from the heart."

When the musicians' attention did swing back to Black Mountain, they re-entered the studio relaxed, refreshed and ready. For two weeks the band lived at Vancouver's Hive studio, sleeping on couches, staying up recording as late as they could and raising their blood-alcohol levels in between. And while the sessions would eventually produce an impressive 19 tracks (10 on In the Future and two others for the Bastards of Light tour 12-inch), McBean still found some moments in the studio a struggle, perhaps showing he's not as laid-back as the media always portrays him. "I think there was a point during this record where I totally hated it," he says, "but that was actually a very short-lived moment. And that happens with anything when you become so involved with it and spend so much time and stress and labour. I'd come away from recording and just hate it. I actually had to stop listening to the songs until we had the mastered copy, and then everything was fine again. Now I'm really proud of it. We're all really proud of it."

This time around, the band also had a clearer focus of what In the Future would be and that included fulfilling McBean's anachronistic fantasies: to make a proper album-album — one that included two slabs of vinyl in a gatefold sleeve, not one built around a few standout tracks. It also had to be an album with just the right, mind-manifesting artwork to encase the sounds within. They didn't have to go far for an artist — Schmidt has a long history in visual art and previously designed covers for Black Mountain singles, as well as those for his own projects. "For Black Mountain, the cover was intrinsic to making the record," says Schmidt, who through cutting and pasting images, eventually came up with the design of a Rubik's-type cube embedded into chilly, rust-coloured terrain. "It's meant to very much look and feel like a classic album cover, in the sense of a gatefold LP. I wanted to make something that was kind of epic but not typically psych looking — something a bit more austere than that, a little more modern, but a little old looking as well. So that's how I arrived at that geometric alien landscape sort of thing." McBean realizes that these back-to-album sentiments may paint him as somewhat of a rock dinosaur, but he can't help but yearn for simpler musical times. "Back in the '70s, when Led Zeppelin IV and all that stuff came out, kids weren't distracted to check their MySpace accounts or got a text message in the middle of 'Stairway to Heaven.' They would slap their headphones on, lie back on their big vinyl beanbag chair and listen to records for hours. Or at least that's what I did as a kid. Now, it's harder, and I wish people could have that experience again now — even if I'm slightly romanticizing it." Adds Schmidt: "I just hope it reminds people of what a great thing a record can be instead of just a download on your iPod shuffle."

Now that In the Future has been recorded, sequenced, packaged and released into the world, McBean likens the experience to someone abducting his child — he wants In the Future back. He wants to immerse himself in it again and iron out all the little quirks that stick out to his ears, but likely no one else's. But he says this strange letting-go happens with every album. And although McBean says he and the band are definitely satisfied with what they've done on In the Future, he can't bring himself to call it his best record, straying far away from words such as masterpiece — a word that could easily apply.

"There was a lot of stuff from the first record where people were like, 'Oh, well, you're just rehashing everything' and saying that we're stealing all this stuff," he says. "But it got to this point where it was like, 'You know, we're in a band and we're just having fun.' We're not trying to reinvent anything and we don't care to. "I've given up on trying to make every record better than the one before. The way I now look at it is that every record is just different, and in the larger scope of things, when you're dead and buried, all the little things you've created will leave one body of work. You just can't try to one-up yourself each time — only put different angles on things.

And so what kind of body of work does McBean want to leave behind? His answer is just as humble as his rock'n'roll dream: "Just a good mix tape. Just one really good 90-minute mix tape."

First on the agenda of their anachronistic ambitions is reviving a traditional idea in how music is presented. "We wanted to get back to the album-album thing, says McBean, the Vancouver group's vocalist, guitar player and principal songwriter, of their sophomore effort, In the Future. "With today's culture of music listening with computers, iPods and even phones now, if you go download an album, you just don't get the whole vibe and the beauty of it all. Music has saved me more than once, just sitting down with a record and looking at the cover, trying to figure out what it means, reading the lyrics and all that stuff.

"I just want some kid to have the same experience that I had with a record at some point. And I'm sure there will probably be a kid who will get baked, start trippin' out on the album cover and be like, 'Ah, dude,' just having that experience with music where it hits you in the heart, in the right place at the right time. Black Mountain's new long-player certainly is an experience. With ten tracks, a 60-minute running time and album art that rivals any Pink Floyd jacket, In the Future is downright overwhelming, demanding you listen, listen and then listen again to absorb it all. It shows the group's members — McBean, Joshua Wells (drums), Amber Webber (vocals), Matt Camirand (bass) and Jeremy Schmidt (keyboards) — stretching far beyond their previous work and doing much more than just resurrecting the ghosts of rock'n'roll past.

In the Future arrives three years after Black Mountain's self-titled debut launched the West Coast five-piece into a whirlwind of acclaim, press and international recognition. Their debut's adventurous reconfiguration of '70s-styled rock hit that sought-after spot where universal appeal meets cult fascination. Garnering one rave review after another, it earned a spot on many critics' best-of lists and caught the eye of the British press, who quickly picked up on the band's hippie-like image and twisted it into fabricated stories of drug-fuelled communes and blissed-out Black Mountain disciples.

In the three years since its release, Black Mountain landed a coveted opening spot on Coldplay's world tour, got "Stay Free" (included on In the Future) onto the Spider-Man 3 soundtrack, and joined Aphex Twin and Julian Cope at the Portishead-curated All Tomorrow's Parties festival in the UK last December.

"You know how everyone has their own rock'n'roll dreams?" McBean asks. "I guess maybe it's because I was a punk kid, but my rock'n'roll dream was to put out a seven-inch and go on tour, and that was it. Now we're long past that."

Getting "long past that" has been a lengthy and often less than glamorous journey for Black Mountain; the group is neither McBean's nor his band-mates' first musical effort by a long shot. McBean's previous project, Jerk with a Bomb, struggled on the Canadian indie scene for years before trekking up to the greener pastures of Black Mountain.

Jerk with a Bomb — a band that at different times housed all of Black Mountain's members except Schmidt, who joined later — first took root in the mid-'90s as a duo composed of McBean and Joshua Wells. At the time, McBean says the folksy rock/country project was a way to escape the angst-driven bands he played in as a teenager, punk-metal outfits like Mission of Christ and Gus, and later on, the short-lived, post-punk-leaning Ex-Dead Teenager (whose only release was released last year on the now-defunct CD-R label, 1777rex).

Jerk with a Bomb had no MySpace or YouTube to kick-start their career, so they began the old-fashioned way: with a demo tape, which fell into the hand of Scratch Records' Keith Parry, who in turn signed the group. Over the years, the Vancouver label put out a handful of JWAB releases, which displayed potential and ambition, but largely fell on deaf ears. "None of the Jerk with a Bomb stuff sold well at all," McBean recalls. "I think it took four or five years for the first Jerk with a Bomb on Scratch [The Old Noise] to get through its first thousand copies." These were lean times for the duo, playing hit-and-miss shows across the country, sleeping in unheated vans and working part-time at the Scratch retail store to avoid eviction notices. By 2003, however, the tide began to change for JWAB when they stretched into more prog-y, stoner-rock territory with their final album, Pyrokinesis. The shift came in part from a line-up change that enlisted two more future Black Mountain recruits: vocalist Amber Webber, who joined JWAB full-time, and bassist Matt Camirand, a former Black Halo who began providing the occasional live support and eventually replaced Pyrokinesis' German multi-instrumentalist, Christoph Hofmeister.

With this new blood and sound, the line where Jerk with a Bomb ended and Black Mountain began blurs. As legend has it, one night before a local show, McBean had a dream JWAB turned into a new band: Black Mountain. When he awoke, he whipped up a banner and a song featuring this new band name. That night, they played as Black Mountain for the first time.

McBean and company decided to keep the new name for good, dropping JWAB's down-and-out folk sounds for the vintage Velvets and Sabbath-like tactics that Pyrokinesis hinted at and Black Mountain fully embraced. "It was almost like a release," McBean says. "It was just like this new thing. I mean, I loved Jerk with a Bomb, but it got to a point where I was done with it, and it almost felt like I was through with that part of my life. I didn't want to stand in front of people and sing sad songs about being heartbroken anymore."

In the Future is much more than just songs for the broken-hearted. Over four sides of vinyl, there are bottom-heavy, bad-boogie-ballin' attacks, prog-fashioned keyboard numbers, soulful freedom songs, occasionally all of the above. There are lyrics of black magic rituals, flower trains, hounds of hell and tyrants dying by the sword. And there are some of the group's most intense, full-on rock moments as well as some of their most tranquil and tender. Together, it adds up to a magnificently sequenced album lover's album with enough hit-the-spot nuggets for the casual shuffler. With the album comes an amplified sense of collaboration — the band sound like one solid unit where each member adds a unique stamp. This especially evident with Webber, whose dramatic, operatic voice wavers stronger than ever behind and in front of McBean's, and Schmidt, his keyboards given free range to sound like the sonic equivalent of outer space as their celestial tones float over Camirand's low bass rumble and Wells's tom-heavy drum patterns.

"Arranging was way more a group thing," McBean explains. "With the first one, a lot of those songs were already written and then Matt and Jeremy came in and did their thing on it. But this time, a lot of stuff was worked on together live first, and everyone would bring in different ideas."

Overall, Black Mountain has made a more varied and heightened musical experience and proven they have evolved far beyond simple rock revivalists, or just McBean's band. "We didn't want to repeat the formula of the first record, having people talk about the Velvets and Sabbath thing again," McBean says. "We had some songs that we could have put on that fit into that, but it just seemed like, 'Why bother? We've already done that.'"

Helping this shift was John Congleton, who mixed all but one of the album's tracks, and who McBean points to as having a major impact on Black Mountain's sonic growth. Without the long-time producer, "the record would have sounded a lot more like the first one," McBean says. Interestingly, it wasn't Congleton's work with rock bands like Polyphonic Spree and Explosions in the Sky that attracted Black Mountain to him; it was what the producer has done with hip-hop and R&B artists like the Roots and R. Kelly. "To me, the album is a logical progression from the first one," says keyboardist Jeremy Schmidt. "It's not a total about-face or anything. There are things are different and, in our minds, improved on. I think there are more fleshed out ideas in terms of our ensemble playing and the contributions of everyone." And while McBean highlights how happy he and the rest of the band are with In the Future, the record was by no means quick and easy. In fact, this is the second time Black Mountain tried to follow up their debut.

After wrapping up tour dates in support of their first album, the band originally entered the studio in March 2006, but most of the material from those sessions ended up on the cutting-room floor, and Black Mountain ended up taking a hiatus. "Bits and pieces of that session worked out, but not all of it, McBean explains. "We had a bunch of songs, but we didn't really have an album; they weren't working together in the right way albums do. And I think our brains were all working on different waves at that point, so we just decided to wait until the band seemed exciting to us again." During this downtime, each member took the opportunity to pursue varied side projects. McBean released the critically adored Axis of Evol under his alter ego, Pink Mountaintops. Wells and Webber recorded an album of gloomy melodrama as Lightning Dust. Camirand set to work on a pair of albums with his Americana-leaning Blood Meridian (which also features Wells on drums), and Schmidt re-released the meditation-inducing sounds of The Enchanter Persuaded, his Sinoia Caves debut.

These creative outlets provided new people to bounce ideas off, Schmidt says, and a place to mine for inspiration that fed back into Black Mountain. "All of our side projects, in one way or another, inform our individual contributions to Black Mountain," he says. "But I think if you put all the side projects together it wouldn't sound like Black Mountain, and if you took Black Mountain all apart, it wouldn't sound like all the individual projects. They're just amalgamations of different aesthetics and sensibilities." McBean also points to the healthy impact the projects had on the band leading up to In the Future. "If we had made the record earlier and not all gone off and done our other little things, this album would not have been as good," McBean says. "It would have been, 'Hey, another record just for the sake of a record.' And none of us really want any of this to become a job — we want it to come from the heart."

When the musicians' attention did swing back to Black Mountain, they re-entered the studio relaxed, refreshed and ready. For two weeks the band lived at Vancouver's Hive studio, sleeping on couches, staying up recording as late as they could and raising their blood-alcohol levels in between. And while the sessions would eventually produce an impressive 19 tracks (10 on In the Future and two others for the Bastards of Light tour 12-inch), McBean still found some moments in the studio a struggle, perhaps showing he's not as laid-back as the media always portrays him. "I think there was a point during this record where I totally hated it," he says, "but that was actually a very short-lived moment. And that happens with anything when you become so involved with it and spend so much time and stress and labour. I'd come away from recording and just hate it. I actually had to stop listening to the songs until we had the mastered copy, and then everything was fine again. Now I'm really proud of it. We're all really proud of it."

This time around, the band also had a clearer focus of what In the Future would be and that included fulfilling McBean's anachronistic fantasies: to make a proper album-album — one that included two slabs of vinyl in a gatefold sleeve, not one built around a few standout tracks. It also had to be an album with just the right, mind-manifesting artwork to encase the sounds within. They didn't have to go far for an artist — Schmidt has a long history in visual art and previously designed covers for Black Mountain singles, as well as those for his own projects. "For Black Mountain, the cover was intrinsic to making the record," says Schmidt, who through cutting and pasting images, eventually came up with the design of a Rubik's-type cube embedded into chilly, rust-coloured terrain. "It's meant to very much look and feel like a classic album cover, in the sense of a gatefold LP. I wanted to make something that was kind of epic but not typically psych looking — something a bit more austere than that, a little more modern, but a little old looking as well. So that's how I arrived at that geometric alien landscape sort of thing." McBean realizes that these back-to-album sentiments may paint him as somewhat of a rock dinosaur, but he can't help but yearn for simpler musical times. "Back in the '70s, when Led Zeppelin IV and all that stuff came out, kids weren't distracted to check their MySpace accounts or got a text message in the middle of 'Stairway to Heaven.' They would slap their headphones on, lie back on their big vinyl beanbag chair and listen to records for hours. Or at least that's what I did as a kid. Now, it's harder, and I wish people could have that experience again now — even if I'm slightly romanticizing it." Adds Schmidt: "I just hope it reminds people of what a great thing a record can be instead of just a download on your iPod shuffle."

Now that In the Future has been recorded, sequenced, packaged and released into the world, McBean likens the experience to someone abducting his child — he wants In the Future back. He wants to immerse himself in it again and iron out all the little quirks that stick out to his ears, but likely no one else's. But he says this strange letting-go happens with every album. And although McBean says he and the band are definitely satisfied with what they've done on In the Future, he can't bring himself to call it his best record, straying far away from words such as masterpiece — a word that could easily apply.

"There was a lot of stuff from the first record where people were like, 'Oh, well, you're just rehashing everything' and saying that we're stealing all this stuff," he says. "But it got to this point where it was like, 'You know, we're in a band and we're just having fun.' We're not trying to reinvent anything and we don't care to. "I've given up on trying to make every record better than the one before. The way I now look at it is that every record is just different, and in the larger scope of things, when you're dead and buried, all the little things you've created will leave one body of work. You just can't try to one-up yourself each time — only put different angles on things.

And so what kind of body of work does McBean want to leave behind? His answer is just as humble as his rock'n'roll dream: "Just a good mix tape. Just one really good 90-minute mix tape."