Gaming has always been an unpredictable beast, but that's especially true this summer. Everyone wrote off Nintendo (again) right up until Pokémon Go dominated the planet, while Overwatch took over multiplayer gaming without the benefit of being a familiar franchise. And who would have guessed that our high-octane current-gen consoles would be best served by a pair of 2D side-scrollers? Yet here we are.

The retro-futuristic exercise in wacky weirdness that is Headlander arrived from indie gaming icon Tim Schafer's Double Fine studio as a followup to their stellar (if developmentally troubled) point-and-click sensation Broken Age.

For fans of their 3D world-building in free-roaming cult classics like Psychonauts and Brutal Legend, before the studio ditched triple-A publishers to go small-scale, Headlander feels limited, but it is literally by design. (Oh, and don't worry, Double Fine is currently crowdfunding Psychonauts 2.)

The main reason why those '80s side-scrolling platformers hold up so well is that the limitations of the 8- and 16-bit eras forced Shigeru Miyamoto and his disciples to express their creativity through ingenious level design. The same basic principal applies to director Lee Petty's Headlander, a side-scroller with a sense of humour, appropriately published by Adult Swim Games.

It's a Metroidvania game, a side-scrolling subgenre named after stylistic '80s innovators Metroid and Castlevania that allows the player to explore giant environments at will, albeit with different areas opening as you progress through and gain new abilities and upgrades.

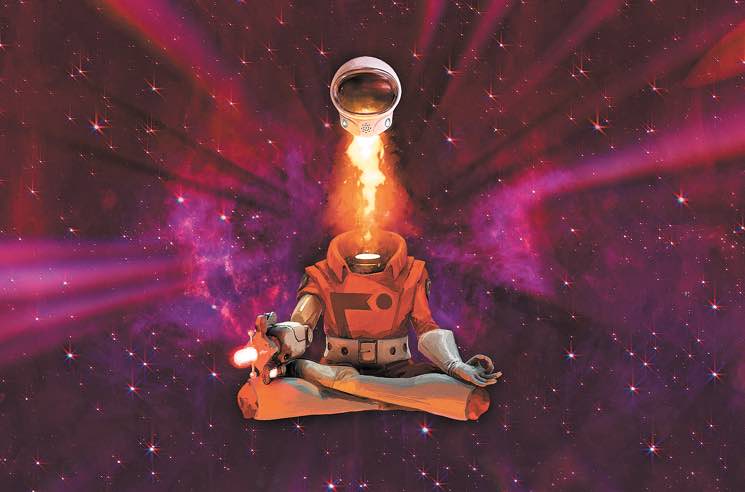

The title is literal, too, in that the primary gameplay conceit is that you control a human head that can land on various robot bodies. Inspired by '70s sci-fi — think Logan's Run or Futureworld — the wonderfully stylized art direction uses the brightly coloured, hand-drawn look of Broken Age to perfectly capture what the past thought the future would be like, complete with dome chairs, "pleasure ports," shag carpets and disco dancing robots. Also, robot dogs and a lot of double-entendre visual gags.

You play the last human left — or rather, part of the last human left. You're just a disembodied noggin in a rocket-powered helmet, while everyone else's consciousness was uploaded into robot bodies to achieve immortality and escape a resource-depleted planet. Except now they're controlled by Methuselah, a HAL-like AI gone rogue. Luckily, you can vacuum suck off their robot heads and land your own meathead on their bodies to manoeuvre your way through the puzzle-replete space station and overthrow its computer overlord.

Then there's Headlanders' aesthetic opposite, the moody and mostly monochromatic Inside by Playdead, the Danish indie studio famed for Limbo, its million-selling 2010 black-and-white side-scroller.

Led by director Arnt Jensen and designer Jeppe Carlsen, the team has been working on their followup for the six years since — and the result is a minimalist masterpiece that bolsters their debut's arresting visual achievement with equally ambitious puzzle-platforming that still restricts itself to a 2D plane.

You play a literal red shirt — one of the game's judicious splashes of colour — which may be a meta joke on how often you will die horrifically. But it also serves to make the young boy you control the beating heart of a dark, dystopian world you are trying to flee without falling to your doom in a factory, having your throat ripped out by dogs while sneaking through a forest or getting captured by the various nefarious folks searching for you.

The wordless narrative, expressed through atmospheric art and environmental puzzles rather than cut-scenes and exposition, involves mad scientists and mind-control, parasitic worms and blob monsters, fear and loathing.

The emotionally evocative Inside is also one of the most acclaimed games of the year, despite being built in a genre that was considered out-dated as soon as the N64 brought 3D gaming into the world in 1996.

Nintendo, of course, never stopped making new side-scrollers — most recently the fantastic 3DS title Kirby: Planet Robobot — but their platformers have always been primarily about recapturing past glories. That's fine, it works for them because they are really, really good at it. But that approach failed for Mega Man creator Keiji Inafune's own summer side-scroller Mighty No. 9, a highly anticipated but eventually critically panned attempt to mine nostalgia despite being an original IP.

Where Headlander and Inside both succeed despite their differing approaches is by employing great videogame design and innovative stylistic ideas to make this old genre, one which defined early console gaming, feel new rather than retro.

The retro-futuristic exercise in wacky weirdness that is Headlander arrived from indie gaming icon Tim Schafer's Double Fine studio as a followup to their stellar (if developmentally troubled) point-and-click sensation Broken Age.

For fans of their 3D world-building in free-roaming cult classics like Psychonauts and Brutal Legend, before the studio ditched triple-A publishers to go small-scale, Headlander feels limited, but it is literally by design. (Oh, and don't worry, Double Fine is currently crowdfunding Psychonauts 2.)

The main reason why those '80s side-scrolling platformers hold up so well is that the limitations of the 8- and 16-bit eras forced Shigeru Miyamoto and his disciples to express their creativity through ingenious level design. The same basic principal applies to director Lee Petty's Headlander, a side-scroller with a sense of humour, appropriately published by Adult Swim Games.

It's a Metroidvania game, a side-scrolling subgenre named after stylistic '80s innovators Metroid and Castlevania that allows the player to explore giant environments at will, albeit with different areas opening as you progress through and gain new abilities and upgrades.

The title is literal, too, in that the primary gameplay conceit is that you control a human head that can land on various robot bodies. Inspired by '70s sci-fi — think Logan's Run or Futureworld — the wonderfully stylized art direction uses the brightly coloured, hand-drawn look of Broken Age to perfectly capture what the past thought the future would be like, complete with dome chairs, "pleasure ports," shag carpets and disco dancing robots. Also, robot dogs and a lot of double-entendre visual gags.

You play the last human left — or rather, part of the last human left. You're just a disembodied noggin in a rocket-powered helmet, while everyone else's consciousness was uploaded into robot bodies to achieve immortality and escape a resource-depleted planet. Except now they're controlled by Methuselah, a HAL-like AI gone rogue. Luckily, you can vacuum suck off their robot heads and land your own meathead on their bodies to manoeuvre your way through the puzzle-replete space station and overthrow its computer overlord.

Then there's Headlanders' aesthetic opposite, the moody and mostly monochromatic Inside by Playdead, the Danish indie studio famed for Limbo, its million-selling 2010 black-and-white side-scroller.

Led by director Arnt Jensen and designer Jeppe Carlsen, the team has been working on their followup for the six years since — and the result is a minimalist masterpiece that bolsters their debut's arresting visual achievement with equally ambitious puzzle-platforming that still restricts itself to a 2D plane.

You play a literal red shirt — one of the game's judicious splashes of colour — which may be a meta joke on how often you will die horrifically. But it also serves to make the young boy you control the beating heart of a dark, dystopian world you are trying to flee without falling to your doom in a factory, having your throat ripped out by dogs while sneaking through a forest or getting captured by the various nefarious folks searching for you.

The wordless narrative, expressed through atmospheric art and environmental puzzles rather than cut-scenes and exposition, involves mad scientists and mind-control, parasitic worms and blob monsters, fear and loathing.

The emotionally evocative Inside is also one of the most acclaimed games of the year, despite being built in a genre that was considered out-dated as soon as the N64 brought 3D gaming into the world in 1996.

Nintendo, of course, never stopped making new side-scrollers — most recently the fantastic 3DS title Kirby: Planet Robobot — but their platformers have always been primarily about recapturing past glories. That's fine, it works for them because they are really, really good at it. But that approach failed for Mega Man creator Keiji Inafune's own summer side-scroller Mighty No. 9, a highly anticipated but eventually critically panned attempt to mine nostalgia despite being an original IP.

Where Headlander and Inside both succeed despite their differing approaches is by employing great videogame design and innovative stylistic ideas to make this old genre, one which defined early console gaming, feel new rather than retro.