It turns out that a surrealist mad man's attempted adaptation of Frank Herbert's Dune is the greatest film never made. In the early 1970s, Alejandro Jodorowsky wanted his $15 million production to recreate the LSD experience and fundamentally change the perspective of a mass audience. His Dune would be "the coming of a God… sacred, free, with new perspective." The sheer lunacy and ambition of this would have made 2001: A Space Odyssey ho-hum. It would have preceded Star Wars by a few years and perhaps changed our entire concept of what a blockbuster film could be.

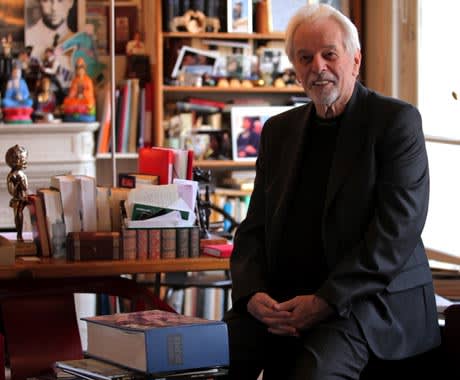

Two things are animated in this documentary: gorgeous original concept art from Jodorowsky's giant coffee table book of Dune (only two were ever printed,) and the 85-year-old's feverish descriptions of his quest. Wisdom shines from his eyes as he describes luring Salvador Dali, Pink Floyd and Orson Welles to participate. When Jodo speaks of himself as a "prophet," it doesn't seem grandiose; it seems almost obvious. Collaborators like Dan O'Bannon and Jean Giraud, who later helped create canonized sci-fi films like Alien and The Fifth Element, are of the same mind.

Already notorious is Jodorowsky's claim that he intended to "rape" Herbert's novel. What he means is that he could not be loyal to the source material, and had to approach it with violence to make it his story. Still, the thrusting motions he uses to emphasize his intent are decidedly unsettling.

Jodorowsky, the director of the original midnight movie, El Topo, and maybe the weirdest shit ever filmed, The Holy Mountain, had not read Dune before he set out to adapt it. He only knew that it was a popular science fiction novel that dealt with consciousness expansion. The cagey Chilean wasn't alone; hardly anyone involved in Jodorowsky's project bothered with Herbert's cornerstone of science fiction, either.

A documentary detailing the destruction of a great artist's major work over a measly $5 million might sound depressing, but it never is, thanks entirely to the élan of its central figure. The only darkness comes when Jodo laments a "system that makes us slaves" and the "evil in our pockets," referring to the money that handcuffs artists who want to work on a monumental scale.

There's nothing dated about this sentiment. Darren Aronofsky's Noah opened last week, and while that other auteur with a four-syllable last name managed to get his film made and released, the process was fraught with studio restrictions from the outset, and many critics consider the result an unpleasing compromise.

The story of Jodorowsky's grand failure should be required viewing for artists at every level of success. The self-described "warrior" issues a simple directive in the final minutes, "If you fail it's not important. We need to try."

(Mongrel Media)Two things are animated in this documentary: gorgeous original concept art from Jodorowsky's giant coffee table book of Dune (only two were ever printed,) and the 85-year-old's feverish descriptions of his quest. Wisdom shines from his eyes as he describes luring Salvador Dali, Pink Floyd and Orson Welles to participate. When Jodo speaks of himself as a "prophet," it doesn't seem grandiose; it seems almost obvious. Collaborators like Dan O'Bannon and Jean Giraud, who later helped create canonized sci-fi films like Alien and The Fifth Element, are of the same mind.

Already notorious is Jodorowsky's claim that he intended to "rape" Herbert's novel. What he means is that he could not be loyal to the source material, and had to approach it with violence to make it his story. Still, the thrusting motions he uses to emphasize his intent are decidedly unsettling.

Jodorowsky, the director of the original midnight movie, El Topo, and maybe the weirdest shit ever filmed, The Holy Mountain, had not read Dune before he set out to adapt it. He only knew that it was a popular science fiction novel that dealt with consciousness expansion. The cagey Chilean wasn't alone; hardly anyone involved in Jodorowsky's project bothered with Herbert's cornerstone of science fiction, either.

A documentary detailing the destruction of a great artist's major work over a measly $5 million might sound depressing, but it never is, thanks entirely to the élan of its central figure. The only darkness comes when Jodo laments a "system that makes us slaves" and the "evil in our pockets," referring to the money that handcuffs artists who want to work on a monumental scale.

There's nothing dated about this sentiment. Darren Aronofsky's Noah opened last week, and while that other auteur with a four-syllable last name managed to get his film made and released, the process was fraught with studio restrictions from the outset, and many critics consider the result an unpleasing compromise.

The story of Jodorowsky's grand failure should be required viewing for artists at every level of success. The self-described "warrior" issues a simple directive in the final minutes, "If you fail it's not important. We need to try."