"If you last long enough, then you can hold your head up high one day."

Dragon Girls, from first time director Inigo Westmeier, tells the story of three Chinese Girls training to become Kung Fu fighters at the Shaolin Kung Fu School. Located adjacent to the famed Shaolin Monastery in Central China, it is the birthplace of Kung Fu, renowned for its monks that can seemingly "fly" (think Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon only without the comb).

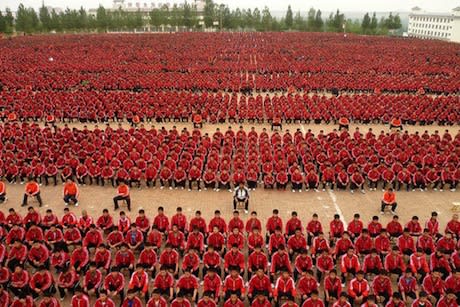

Westmeier's documentary follows three female pupils in a crowd of over 26,000 children who are under strict pressure to conform to the school's stringent guidelines. To give an idea of how astounding this number really is, intricately constructed scenes featuring thousands of students exercising and training in perfect formation dissolve and rapidly focus in on a single student to show viewers how the single contributes to the whole.

Students face a rigid, performance-oriented instruction, which includes a regimented daily schedule, poor living conditions, poor food and frequent beatings in the name of nationalist self-discipline. One scene shows a group of young women comparing scars they have endured through their trainings, showing off their injuries and laughing about how they occurred—many training sessions involve the pupils leaping and somersaulting while using sharp swords, daggers and spears.

While most of the students at the school are male, Westmeier chooses to focus on the females, reiterating a common Western perception of Chinese ideology, finding importance in the women amidst a culture that values the importance of a male heir to carry on the family name. The young women come to the school for a variety of reasons—disciplinary issues, being unwanted by their family and having no one to care for them to name a few—but all are there under the basic assumption of future betterment, having an education from a renowned institution.

Juxtaposed with the schoolgirls is a young woman that recently escaped, citing stringent guidelines, beatings and impossible living conditions as her rationale. Scenes of her playing for hours at her computer with very little ambition and promise for the future underscore the fact that, regardless of the hardships the students endure, they are working towards a brighter future.

Scenes of extreme discipline occasionally break for brief moments of downtime. Westmeier reminds viewers that we're dealing with humans or, more importantly, little girls. These girls are seen at payphones trying to call home, looking for support only to be met with no answer or parents that refuse to placate their needs.

Given Westmeier's background as a cinematographer, the exquisite composition and grandiose compositional vernacular of the film is unsurprising. The overhead shots of the students participating in mass performances in the school's quad are as mindblowing as the intimate takes of individual action. His vacillation between the individual and the mass reinforced the idea of individual identity in relation to the bigger ideal, which, given the role of his female subjects politically proves particularly intriguing, adding a greater dimension of thought to an already compelling superficial examination of a lifestyle and method of personal betterment.

(Kinosmith)Dragon Girls, from first time director Inigo Westmeier, tells the story of three Chinese Girls training to become Kung Fu fighters at the Shaolin Kung Fu School. Located adjacent to the famed Shaolin Monastery in Central China, it is the birthplace of Kung Fu, renowned for its monks that can seemingly "fly" (think Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon only without the comb).

Westmeier's documentary follows three female pupils in a crowd of over 26,000 children who are under strict pressure to conform to the school's stringent guidelines. To give an idea of how astounding this number really is, intricately constructed scenes featuring thousands of students exercising and training in perfect formation dissolve and rapidly focus in on a single student to show viewers how the single contributes to the whole.

Students face a rigid, performance-oriented instruction, which includes a regimented daily schedule, poor living conditions, poor food and frequent beatings in the name of nationalist self-discipline. One scene shows a group of young women comparing scars they have endured through their trainings, showing off their injuries and laughing about how they occurred—many training sessions involve the pupils leaping and somersaulting while using sharp swords, daggers and spears.

While most of the students at the school are male, Westmeier chooses to focus on the females, reiterating a common Western perception of Chinese ideology, finding importance in the women amidst a culture that values the importance of a male heir to carry on the family name. The young women come to the school for a variety of reasons—disciplinary issues, being unwanted by their family and having no one to care for them to name a few—but all are there under the basic assumption of future betterment, having an education from a renowned institution.

Juxtaposed with the schoolgirls is a young woman that recently escaped, citing stringent guidelines, beatings and impossible living conditions as her rationale. Scenes of her playing for hours at her computer with very little ambition and promise for the future underscore the fact that, regardless of the hardships the students endure, they are working towards a brighter future.

Scenes of extreme discipline occasionally break for brief moments of downtime. Westmeier reminds viewers that we're dealing with humans or, more importantly, little girls. These girls are seen at payphones trying to call home, looking for support only to be met with no answer or parents that refuse to placate their needs.

Given Westmeier's background as a cinematographer, the exquisite composition and grandiose compositional vernacular of the film is unsurprising. The overhead shots of the students participating in mass performances in the school's quad are as mindblowing as the intimate takes of individual action. His vacillation between the individual and the mass reinforced the idea of individual identity in relation to the bigger ideal, which, given the role of his female subjects politically proves particularly intriguing, adding a greater dimension of thought to an already compelling superficial examination of a lifestyle and method of personal betterment.