While epic series like The Lord of the Rings, The Matrix and Kill Bill have been waging testosterone fuelled battles for the top of the commercial box office over the past few years, Matthew Barney, one of contemporary America's leading artists, has created a stunning and challenging epic five-film series based around the cremaster muscle, the controller of those most fundamental of male sexual organs, the testes, and particularly the muscle's response to different external and internal stimuli.

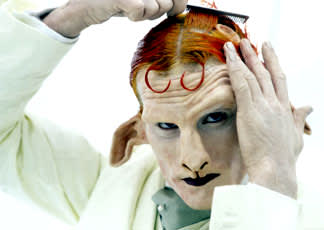

A sculptor and installation artist with a strong interest in the relationship between team sports, his personal growth in Boise, Idaho, the individual and public creation of mythologies, and the biology of sexual identity, Barney stars in each film as a very particular creation, typically the protagonist, and encounters just about the widest array of reconstructed figures you're likely to find in film, from serial killer Gary Gilmore to his possible grandfather, Harry Houdini (played by Norman Mailer).

While the narrative of the entire cycle follows similar thematic concepts, each film is also a project unto itself, complete with accompanying sculptures and installations, progressively tackling non-biologically associated responses of the cremaster. The most recent, longest and possibly most realised is Cremaster 3, essentially a study of New York City's Chrysler Building as seen through the eyes of its chief architect and an entered apprentice architect, Barney, who duplicitously moves his way up the building.

Along his route, Barney interacts with various individuals who take an interest in his cheating ambitions, and, in the second half, he's forced to confront five levels of particular challenges to achieve his desired victories, and consequently face his inevitable ambition-induced doom.

While at times not the most affecting of personal experiences, the films often contain a unique humour, perspective and an inspiring questioning curiosity. But most of all, and to its benefit, The Cremaster Cycle is an extremely singular visual experience made unique through Barney's obsessively intricate and surprisingly intimate cartography of the clash between his private and public spheres. (Mongrel Media)

A sculptor and installation artist with a strong interest in the relationship between team sports, his personal growth in Boise, Idaho, the individual and public creation of mythologies, and the biology of sexual identity, Barney stars in each film as a very particular creation, typically the protagonist, and encounters just about the widest array of reconstructed figures you're likely to find in film, from serial killer Gary Gilmore to his possible grandfather, Harry Houdini (played by Norman Mailer).

While the narrative of the entire cycle follows similar thematic concepts, each film is also a project unto itself, complete with accompanying sculptures and installations, progressively tackling non-biologically associated responses of the cremaster. The most recent, longest and possibly most realised is Cremaster 3, essentially a study of New York City's Chrysler Building as seen through the eyes of its chief architect and an entered apprentice architect, Barney, who duplicitously moves his way up the building.

Along his route, Barney interacts with various individuals who take an interest in his cheating ambitions, and, in the second half, he's forced to confront five levels of particular challenges to achieve his desired victories, and consequently face his inevitable ambition-induced doom.

While at times not the most affecting of personal experiences, the films often contain a unique humour, perspective and an inspiring questioning curiosity. But most of all, and to its benefit, The Cremaster Cycle is an extremely singular visual experience made unique through Barney's obsessively intricate and surprisingly intimate cartography of the clash between his private and public spheres. (Mongrel Media)