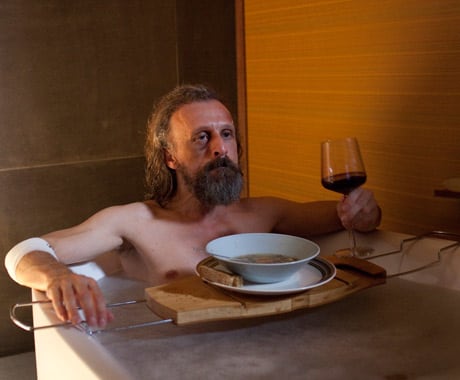

In Borgman, Dutch director Alex van Warmerdam offers no clues or hints as to how viewers should feel, making it an altogether confusing and dark experience. The film starts in medias res, with a priest and two rogues wielding shotguns and axes, hunting a homeless looking man that lives underground. That man — the titular Camiel Borgman — gains the sympathy of Marina, a well-off mother of three, by posing as a beggar looking for a bath after being beaten up by her husband, Richard. She allows Borgman to stay in the summerhouse behind their home, feeding him and bathing him secretly until he disappears one day. Borgman poisons the family's gardener, and appears at their door, clean-shaven and unrecognizable, when they search for a new man to fill the position. Borgman is hired by Richard as a live-in landscaper, and after gaining the trust of the family and access to their home, he is able to psychologically torture Marina, brainwash their three children, and kill Richard.

Van Warmerdam incorporates shades of surrealism with quick cuts of bizarre, sometimes graphic footage without context or explanation. A shot of polished knives and razors, a graceful ballerina pirouetting on the lawn, a ghostly greyhound slinking silently through the house — by weaving these images smoothly into the regular progression of the plot, without logical context, van Warmerdam raises questions that the film never answers. The film is also rife with repetitive imagery: a long scar between the shoulder blades, mixing cement, a naked Borgman perched upon a sleeping Marina. These motifs offer the only sense of continuity throughout the film, and viewers will find themselves clinging to the strange comfort of these familiar images.

Van Warmerdam abandons diegetic sound and background music almost completely. The lack of outside sound is chilling, and there's no music to offer emotional cues to the audience. In addition, van Warmerdam focuses shots on parts of the body that do not convey emotion: torsos, elbows and legs. With these unique approaches to framing and sound, van Warmerdam challenges his audience to interpret the film without cues or hints.

Jan Bijvoet offers a terrifying performance as Camiel Borgman. He takes advantage of the children's naive trust, and engages them with bedtime stories on the first night he spends in the house, when he is still staying in the summerhouse. Bijvoet and Elve Lijbaart (who plays Isolde, the youngest of the three children) have an unsettling chemistry. Borgman's control over Isolde is particularly terrifying, as it plays off the paranoia a parent feels when their children talk to strangers.

Van Warmerdam highlights the potential chaos that a confined, comfortable, suburban life can hold. Engrained in that chaos is paranoia about social class boundaries, evident in Richard's violent rejection to the proposal of having a homeless man enter his home. Oppositely, Borgman also acts as a kind of warning, a cautionary tale against blindly trusting a stranger. The concept of hiring a domestic worker that turns murderous isn't groundbreaking, but van Warmerdam has taken it to new heights with Borgman's sadistic psychological torture.

Borgman is frustrating at times, as the viewer's constant quest for meaning and reason is endlessly thwarted by van Warmerdam's chaotic plot and imagery. Despite its shades of social and economic commentary, Borgman is seemingly meant to remain unexplained. The film progresses from strange but benign plot progressions to wholly sinister insanity. No matter how hard a viewer tries to interpret it, Borgman raises questions that aren't necessarily meant to be answered.

(Films We Like)Van Warmerdam incorporates shades of surrealism with quick cuts of bizarre, sometimes graphic footage without context or explanation. A shot of polished knives and razors, a graceful ballerina pirouetting on the lawn, a ghostly greyhound slinking silently through the house — by weaving these images smoothly into the regular progression of the plot, without logical context, van Warmerdam raises questions that the film never answers. The film is also rife with repetitive imagery: a long scar between the shoulder blades, mixing cement, a naked Borgman perched upon a sleeping Marina. These motifs offer the only sense of continuity throughout the film, and viewers will find themselves clinging to the strange comfort of these familiar images.

Van Warmerdam abandons diegetic sound and background music almost completely. The lack of outside sound is chilling, and there's no music to offer emotional cues to the audience. In addition, van Warmerdam focuses shots on parts of the body that do not convey emotion: torsos, elbows and legs. With these unique approaches to framing and sound, van Warmerdam challenges his audience to interpret the film without cues or hints.

Jan Bijvoet offers a terrifying performance as Camiel Borgman. He takes advantage of the children's naive trust, and engages them with bedtime stories on the first night he spends in the house, when he is still staying in the summerhouse. Bijvoet and Elve Lijbaart (who plays Isolde, the youngest of the three children) have an unsettling chemistry. Borgman's control over Isolde is particularly terrifying, as it plays off the paranoia a parent feels when their children talk to strangers.

Van Warmerdam highlights the potential chaos that a confined, comfortable, suburban life can hold. Engrained in that chaos is paranoia about social class boundaries, evident in Richard's violent rejection to the proposal of having a homeless man enter his home. Oppositely, Borgman also acts as a kind of warning, a cautionary tale against blindly trusting a stranger. The concept of hiring a domestic worker that turns murderous isn't groundbreaking, but van Warmerdam has taken it to new heights with Borgman's sadistic psychological torture.

Borgman is frustrating at times, as the viewer's constant quest for meaning and reason is endlessly thwarted by van Warmerdam's chaotic plot and imagery. Despite its shades of social and economic commentary, Borgman is seemingly meant to remain unexplained. The film progresses from strange but benign plot progressions to wholly sinister insanity. No matter how hard a viewer tries to interpret it, Borgman raises questions that aren't necessarily meant to be answered.