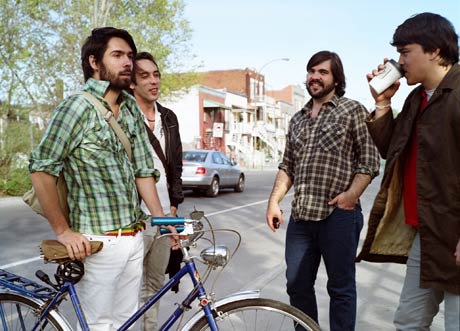

"Thats what the studio looks like in my mind, says Wolf Parades Dan Boeckner, only semi-facetiously. Hes referring to the cover art for the bands second album, At Mount Zoomer, named after the Montreal studio where they began work on the long awaited follow-up to Apologies to the Queen Mary.

Designed by Matt Moroz and Elizabeth Huey, the cover image features what Boeckner describes as "a demon-faced man emerging from the ground with a gnome in his hand, below a strange interlocking structure that bears some resemblance to Montreals ubiquitous highway overpasses, a source of controversy since a collapse in the satellite city of Laval killed five people and seriously injured six in the fall of 2006. The following summer, Wolf Parade "sound manipulator Hadji Bakara helped coordinate a pair of semi-legendary parties underneath an overpass in Montreals renowned cultural hotbed, Mile-End, plying the concrete structures foundation with thousands of watts of sound and hundreds of pairs of dancing shoes. Plans are now in place to demolish parts of the towering grey web that connects the islands boroughs and suburbs, a project that will yield the biggest aesthetic transformation Montreal has seen since the overpasses were erected in the 70s.

"All this work here, just to tear it down, Boeckner sings on "Language City. And while hes not explicitly commenting on Montreals decaying infrastructure in that song which isnt inspired by provincial politics either; hes said its about the pointlessness of all-night coke parties the themes of urban malaise and isolation care of technology are woven through the record, the making of which mirrors a dual longing for escape and homecoming expressed in its lyrics.

"If [the studio] had left an emotional imprint on my brain, adds Boeckner, "it would look a lot like [the cover]: a little messy, kinda disorganised, a little dark, kinda weird. Following a series of songwriting sessions at Mount Zoomer in Mile-End, the band drove roughly 90 minutes southeast and holed up in Arcade Fires church studio in Farnham, Quebec, where Neon Bible was recorded.

"It allowed us to get out of town, but not really out of town, says drummer/engineer Arlen Thompson. "It was free, Boeckner adds. "Well, sorta free. We had to cut the lawn. But it was nice to all be sleeping in the same spot. "Same bed, interjects Spencer Krug. "Same bed, yeah, says Boeckner, "whispering ideas to each other. When they werent mowing the grass or manning the barbecue, the quartet burned the midnight oil to build an album from scratch. According to Sub Pops website, a batch of songs were written and scrapped because they sounded too similar to tracks from Apologies, a claim the band refutes.

"The default setting for this round of interviews has been denying internet rumour, says Boeckner. The songs in question were actually written years ago, around the time their debut album was released, and anyone whos seen Wolf Parade live has heard them those songs were a fixture of their set list. "I dont think we even remember how to play them, says Thompson, "but we didnt have any interest in picking up those ghosts.

The other inaccuracy that Wolf Parade continues to encounter is that the band were on hiatus while three of its members attended to other bands. Handsome Furs, Boeckners duo with his wife Alexei Perry, released an album in the spring of 2007, and toured substantially; Krugs band, Sunset Rubdown, has released three LPs and one EP since the summer of 2005 (the first album preceded Apologies by three months), and Krug even found time for Swan Lake, a three-way collaboration with Dan Bejar of Destroyer and Carey Mercer of Frog Eyes, the Victoria, B.C., band that once included Krug in its ranks. And Bakaras Megasoid, a duo with DJ Sixtoo, is a hard-hitting electronic outfit that has played countless regional concerts and dance parties, including those aforementioned overpass shindigs. These are all stand-alone endeavours, undeserving of the somewhat dismissive "side project tag, and each obviously required ample time for gestation and execution. But somehow, it was never to the detriment of Wolf Parade.

"We did a whole bunch of tours after Apologies came out, explains Boeckner. "Even up to last year, we were averaging about one-and-a-half North American tours a year, and still rehearsing. While its still possible, in a couple of cases, to pinpoint "Dan songs and "Spencer songs on this record, theres truth in the widespread observation that the material sounds more unified than it did previously.

"Playing in side projects probably just created a way of exorcising other ideas, growing musically outside of Wolf Parade, said Krug. "We all got better at playing together and communicating musically with each other, Boeckner adds, "so I think it was natural that things just fell together a little more. Though the band has no template for their songwriting method, and wouldnt want to fall into a routine, Krug says that much of At Mount Zoomer was the result of "complete collaboration.

"Theres no collaboration on lyrics, but half the songs on this record were born out of improv sessions that we edited down into songs that we could play together, Krug explains. "Somewhere early on in the process, we just decided, or it just evolved naturally, who was going to sing what Ive never thought about what dictates that. [Call It a Ritual] came about one day where we just started playing drums and piano and we liked the riff and so we just recorded it that afternoon, whipped something up. "The other half were things that either Dan or I started independently at home, really basically, minimally, like, Heres some riffs, heres some sounds, and then the band took it from there.

With Thompson doubling as producer, At Mount Zoomer was a strictly insular undertaking, one the band wanted to render without the polish of its predecessor. Though pop impulses remain at the core of their craft, and the record has no shortage of hooks, the band widens their scope with warped, episodic songs such as the epic closer, "Kissing the Beehive, and a greater variety of tones, tempos and sonic textures. An organic approach was key to the records vibrancy, and road-testing the tunes was an invaluable part of the process.

"Id say about three-quarters of the album became the set that we were playing on our last tour, Boeckner says. "There are only two new songs that we didnt play and they were new to everybody, the audience and us. It was nice to be able to play songs that we were really excited about, that hadnt coalesced in a recorded state. It was a chance to let the songs grow organically in front of people.

"All this work here, just to tear it down, Boeckner sings on "Language City. And while hes not explicitly commenting on Montreals decaying infrastructure in that song which isnt inspired by provincial politics either; hes said its about the pointlessness of all-night coke parties the themes of urban malaise and isolation care of technology are woven through the record, the making of which mirrors a dual longing for escape and homecoming expressed in its lyrics.

"If [the studio] had left an emotional imprint on my brain, adds Boeckner, "it would look a lot like [the cover]: a little messy, kinda disorganised, a little dark, kinda weird. Following a series of songwriting sessions at Mount Zoomer in Mile-End, the band drove roughly 90 minutes southeast and holed up in Arcade Fires church studio in Farnham, Quebec, where Neon Bible was recorded.

"It allowed us to get out of town, but not really out of town, says drummer/engineer Arlen Thompson. "It was free, Boeckner adds. "Well, sorta free. We had to cut the lawn. But it was nice to all be sleeping in the same spot. "Same bed, interjects Spencer Krug. "Same bed, yeah, says Boeckner, "whispering ideas to each other. When they werent mowing the grass or manning the barbecue, the quartet burned the midnight oil to build an album from scratch. According to Sub Pops website, a batch of songs were written and scrapped because they sounded too similar to tracks from Apologies, a claim the band refutes.

"The default setting for this round of interviews has been denying internet rumour, says Boeckner. The songs in question were actually written years ago, around the time their debut album was released, and anyone whos seen Wolf Parade live has heard them those songs were a fixture of their set list. "I dont think we even remember how to play them, says Thompson, "but we didnt have any interest in picking up those ghosts.

The other inaccuracy that Wolf Parade continues to encounter is that the band were on hiatus while three of its members attended to other bands. Handsome Furs, Boeckners duo with his wife Alexei Perry, released an album in the spring of 2007, and toured substantially; Krugs band, Sunset Rubdown, has released three LPs and one EP since the summer of 2005 (the first album preceded Apologies by three months), and Krug even found time for Swan Lake, a three-way collaboration with Dan Bejar of Destroyer and Carey Mercer of Frog Eyes, the Victoria, B.C., band that once included Krug in its ranks. And Bakaras Megasoid, a duo with DJ Sixtoo, is a hard-hitting electronic outfit that has played countless regional concerts and dance parties, including those aforementioned overpass shindigs. These are all stand-alone endeavours, undeserving of the somewhat dismissive "side project tag, and each obviously required ample time for gestation and execution. But somehow, it was never to the detriment of Wolf Parade.

"We did a whole bunch of tours after Apologies came out, explains Boeckner. "Even up to last year, we were averaging about one-and-a-half North American tours a year, and still rehearsing. While its still possible, in a couple of cases, to pinpoint "Dan songs and "Spencer songs on this record, theres truth in the widespread observation that the material sounds more unified than it did previously.

"Playing in side projects probably just created a way of exorcising other ideas, growing musically outside of Wolf Parade, said Krug. "We all got better at playing together and communicating musically with each other, Boeckner adds, "so I think it was natural that things just fell together a little more. Though the band has no template for their songwriting method, and wouldnt want to fall into a routine, Krug says that much of At Mount Zoomer was the result of "complete collaboration.

"Theres no collaboration on lyrics, but half the songs on this record were born out of improv sessions that we edited down into songs that we could play together, Krug explains. "Somewhere early on in the process, we just decided, or it just evolved naturally, who was going to sing what Ive never thought about what dictates that. [Call It a Ritual] came about one day where we just started playing drums and piano and we liked the riff and so we just recorded it that afternoon, whipped something up. "The other half were things that either Dan or I started independently at home, really basically, minimally, like, Heres some riffs, heres some sounds, and then the band took it from there.

With Thompson doubling as producer, At Mount Zoomer was a strictly insular undertaking, one the band wanted to render without the polish of its predecessor. Though pop impulses remain at the core of their craft, and the record has no shortage of hooks, the band widens their scope with warped, episodic songs such as the epic closer, "Kissing the Beehive, and a greater variety of tones, tempos and sonic textures. An organic approach was key to the records vibrancy, and road-testing the tunes was an invaluable part of the process.

"Id say about three-quarters of the album became the set that we were playing on our last tour, Boeckner says. "There are only two new songs that we didnt play and they were new to everybody, the audience and us. It was nice to be able to play songs that we were really excited about, that hadnt coalesced in a recorded state. It was a chance to let the songs grow organically in front of people.